There But For The Grace Of God

On 'Moral Failings' & A Saying We Should Maybe Quit Saying

Disclaimer: I’ve written this piece for men. Ladies, you are more than welcome to read and respond (you’ll probably like it better). But I wanted to clarify my target audience. Carry on.

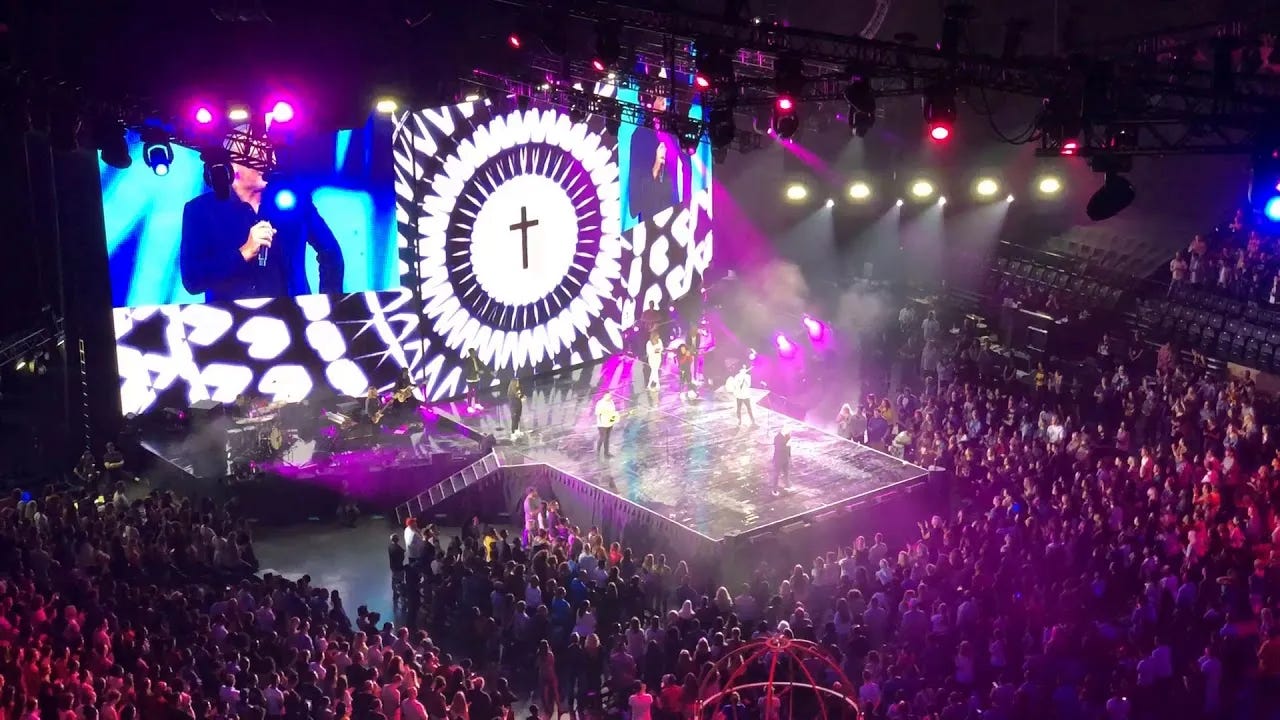

Former megachurch pastor Carl Lentz has re-emerged to the public eye after his highly publicized dismissal from Hillsong NYC almost four years ago due to “moral failings.” Before the scandal, Lentz was already highly publicized, but in a much more positive light, rubbing shoulders with celebrities like Justin Bieber, Kevin Durant, Oprah, and the hosts of The View. At the time of his firing, an ongoing affair with one woman outside the church had come to light. Since then, several other extramarital affairs and episodes from the past, within and beyond the church, have been unearthed. In the first episode of their podcast, Lentz addressed the headlines naming him a “disgraced pastor.”

What’s funny about that is—God bless those people—they don’t understand grace. You can’t fall from grace. You fall into grace…Grace is mercy and favor that you do not deserve but God gives it to you anyway. If anything, I fell into grace. And if people could stop writing headlines like that, I would appreciate it, because it’s inaccurate. I’m not a disgraced former pastor. I am a human being who made huge mistakes. Mine were public. Everybody got to see them. And now I’m a human being that’s trying to rectify my life. But disgraced, I am not. I’m more filled with grace than I’ve ever been. Did I fall from grace? Absolutely not. I fell into it, and I’m grateful for that. You could say what I did was disgraceful. Maybe at times, sure. But I’m not disgraced, because we’re forgiven and I have been able to feel God’s grace more than ever…You can keep writing that headline if you want, but I don’t identify as the disgraced former pastor. No sir. No ma’am.

It’s a clever turn of phrase, the kind he was famous for in a former life: “I didn’t fall from grace; I fell into it.” Lentz’s style is warm and approachable. His spoken words come across as more modest and less defensive than they might appear to the reader. And for those of us who have grown up as adherents of “the gospel of grace,” it is hard to deny him his point. If grace is God’s unmerited, unconditional favor, how could you ever fall out of it?

Even still, I believe that Lentz is revealing here a subtle but profound misunderstanding—of his role, of his sin, and of the very meaning of grace—which is not his only, but has become pervasive in our contemporary Evangelical climate. In what follows, I hope to show you what I mean. But first, let’s acknowledge an epidemic.

In our local congregations in the age before the internet, there perhaps existed some natural limit to the number of times one could feel betrayed by his or her spiritual leaders. In our time, it is a bi-weekly occurrence. When the news of the “moral failings” of well-known Christian teachers and pastors like Carl Lentz and Steve Lawson come across our screens almost as often as that of mass shootings, one begins to wonder which of these two modern tragedies is more successfully eroding our national faith. Nihilistic violence may shock the soul, but continued spiritual betrayal is almost too much for the human heart to bear. For relational beings, nothing—not even death—is so disorienting as the divorce of trust and trustworthiness.

There are those who will say that Christians, of all people, should be the least surprised by the frequency and profundity of such failures. Original sin, G. K. Chesterton once quipped, is the only Christian doctrine which can be easily observed in the street. In the street, yes. But in the church? Yes, there too, Lord help us. And yet, what are we to make of this fact? Does our acknowledgment of original–and ongoing–sin logically necessitate the inevitable breach of trust by our spiritual leaders? Have we really grown that cynical?

Most of us have become accustomed to the unfolding liturgy of online announcements, apologies, and vague allusions to impropriety which accompany the falling of a pastor. In such announcements, specificity is rarely offered, not even the G-rated version, not even to the congregation. This modern liturgy of the church is generally followed by the modern liturgy of the disgraced pastor, who tries, often sincerely, to show just how sorry he is for what he was caught doing. Often he concludes his brief formal statement with a request for privacy for himself and his family in this time, as he seeks help, healing, and the restoration of his marriage. Of course, we lament the stilted, impotent formality of the whole thing, but to some degree we accept it. And though we hate it, we also understand it. All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God. “There, but for the grace of God, go I,” we say.

But grace is not a fickle good-luck charm, which just so happened to keep you out of the ditch so far, while other unlucky souls counting on the same “grace” keep falling in. If that is your view of grace, I wish you luck. No, in the Christian view, grace is the power of God, which works in us to will and to act according to his good purpose. “The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ,” one of Saint Paul’s favorite phrases, is a firm foundation for our faith and faithfulness, not a fleeting wind, which sometimes allows a man to be faithful to his wife and sometimes not. Moreover, sexual immorality is not a “mistake,” as Lentz calls it. The kind of sin that destroys a church, explodes a family and ruins a legacy is not a random ditch you happened to fall into. Sexual unfaithfulness does not come as a tornado, missing this house and that house and hitting yours. It is more like a tree which has been growing up from underneath your house, which broke through the floorboards years ago, which you and perhaps your loved ones have been inconveniently circumventing to get from the kitchen to the dining room on a regular basis. Now it has finally broken your house in pieces, and you act surprised.

But grace is a tree too. A tree with roots as deep as its branches are tall, a tree which always bears fruit in season. Grace is no fleeting breeze, but the very sure gift of God, the trustworthiness of Christ, as certain as the sunrise. Why then, do we besmirch its meaning with a saying which highlights our own untrustworthiness as members of his Body and Spirit: “There, but for the grace of God, go I?”

I think I understand why. After all, I have used it myself. The expression can take on different meanings. Sometimes it simply refers to someone else’s bad luck. This makes sense. But when spoken in the context of someone’s moral failure, I think it can have three possible interpretations: (1) “I might have done the same, in the past;” (2) “I might have done the same, even now;” (3) “We are all the sort of people that could do exactly this thing, at any time.”

The first is a personal admission of humble gratitude that you too might have fallen in a similar way, if you had not started walking in the new life and light of Christ, in which such practices are no longer plausible. I suspect that quite a number of believers use the saying this way, and that makes sense. The second, unlike the first, is a profound admission of present guilt. The speaker is saying, in effect, “I—not all men, but I—am as guilty as he, for I continue to do in my heart what he has now done with his body.” This second usage, in my experience, is rare, given that the admission of sin is personal and specific, not generic and doctrinal. This is the tax collector, not abstractly reflecting on “sin,” but beating his breast and asking for deliverance. Again, rare, but very good. This is a man on the cusp of true repentance. The third speaker may use the same words as the second, but his meaning is almost the opposite. He speaks “theologically.” He wields the doctrinal truth of sin for the subtle purpose of concealing rather than revealing his own love of the darkness. He appears humble, because he is speaking in the first person singular. But his meaning is vague and generic, much like his conviction. He may be “a follower of Jesus,” but he is, at best, unfamiliar with the Jesus who said,

If your right eye causes you to sin, tear it out and throw it away. For it is better that you lose one of your members than that your whole body be thrown into hell. And if your right hand causes you to sin, cut it off and throw it away. For it is better that you lose one of your members than that your whole body go into hell. (Matthew 5:29-30)

Admittedly, many would probably say their meaning falls somewhere in between #2 and #3. But to fall in between the two is ultimately to fall into #3. “There but for the grace of God go I,” is either a call to urgent action…or it is not. At least, in the communities I have been a part of, it usually is not. And if not, it is very often being used as a subtle, even unconscious, self-protection against true repentance.

“But,” some may protest, “Even the Apostle Paul referred to himself as the chief of sinners (1 Tim. 1:15)!”

Yes, he did. But the common use of this phrase is painfully disconnected from its context. Paul refers to himself as “chief of sinners” not to highlight his untrustworthiness, but on the contrary, to emphasize that he has now been deemed trustworthy.

I thank him who has given me strength, Christ Jesus our Lord, because he judged me faithful, appointing me to his service, though formerly I was a blasphemer, persecutor, and insolent opponent. But I received mercy because I had acted ignorantly in unbelief, and the grace of our Lord overflowed for me with the faith and love that are in Christ Jesus. (1 Timothy 1:12-14)

In other words, Paul is speaking in sense #1. If we need further proof, he then exhorts Timothy to persevere in like manner: “wage the good warfare, holding faith and a good conscience,” [lest you become like others] “who have made shipwreck of their faith” (vv. 18-20).

Imagine if Timothy had responded to Paul’s exhortation saying that he may or may not shipwreck his faith, depending on what the grace of God had in store for him. Again, we do speak this way in the wake of church scandals, and appear humble. But the renouncing of personal agency among Christian men regarding sexual sin is no virtue; it is cowardice. Were our marriage vows really a promise, or were they only a wish? Did we cross our theological fingers when we promised, “til death do us part?” Did we shrug our shoulders and say, “I do...you know, barring the ongoing effects of total depravity.” Are there Christian leaders out there who are willing to say that the very notion of wedding vows is disingenuous and sub-Christian, since no sinful human could ever know with certainty whether he will betray his bride? If so, let them speak up at the wedding services over which they preside, not years later when they appear unsurprised at the breaking of vows by believers, even leaders in the church. Let them declare in their wedding homily, “If we were truly humble, we would make no promises at all!”

This is, of course, nonsense. But too many Christians, especially men, have grown up under exactly this kind of assumption. We “struggle with pornography” instead of renouncing it. Or else we renounce it–for now–until the next time we “fall into temptation.” “But God is gracious!” we declare amidst the safe, casual secrecy of our peers, even as we preside over families and churches who absolutely rely on our integrity. We forget that Paul has more words to say on the subject:

Do you presume on the riches of his kindness and forbearance and patience, not knowing that God's kindness is meant to lead you to repentance? (Romans 2:4)

Or do you not know that the unrighteous will not inherit the kingdom of God? Do not be deceived: neither the sexually immoral, nor idolaters, nor adulterers, nor men who practice homosexuality, nor thieves, nor the greedy, nor drunkards, nor revilers, nor swindlers will inherit the kingdom of God. And such were some of you. But you were washed, you were sanctified, you were justified in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ and by the Spirit of our God. (1 Corinthians 6:9-11)

Even worse, we who are leaders in the church forget that Paul, as a leader, set an example by declaring, “Imitate me as I imitate Christ.” (1 Corinthians 11:1) Do we have the courage to say this of ourselves? How could Paul say it, having declared himself the “chief of sinners?” He could say it, not because of his own strength, but precisely because of the grace of God. He could say it, because grace is the power to keep promises, not merely—not even fundamentally—the ability to be excused when we do not. The grace of God is no mere forgiveness for our inability to love God and others. It includes forgiveness, of course, but it does not simply “let us off” or “let us be.” It is a gift with strings attached, and those strings mercifully bind us to Him. The gift of grace affords us the salvation of true relationship, of trust and trustworthiness. It affords us the ability, finally, to love Him and be faithful to Him as he has been to us. Otherwise it is no salvation at all, and we are still in the grip of sin and death.

Unfortunately, for Carl Lentz—and even more for his wife and family with whom he has apparently made amends, and even more for the countless souls under his pastoral care with whom he has not—it is very possible to fall from grace. I understand his meaning, about “falling into grace.” There is truth in it. The mercy of God knows no end. Not to mention, for a man living a double life, there is a certain ecstasy, a la Crime and Punishment, in being caught. How much more so in the realization that God has not yet struck you dead like Ananias and Sapphira? I fully believe that he and his wife are experiencing the personal restoration they claim to be experiencing. But I cannot overstate just how far that falls short of the scope of restoration required in cases like his. Carl Lentz is not just “a human being trying to rectify his mistakes,” as he puts it. He is also a former pastor to whom tens of thousands of people gave spiritual authority. (And I don’t mean to pick on Carl in particular. You may fill in the blank.) The point is, none of us are the autonomous individuals we imagine ourselves to be. Our sins, even our private sins, are not as private as they seem. What I do “in the privacy of my own home” does affect my neighbors to the degree to which they are connected to and counting on me. For pastors, priests, and spiritual leaders, this is a very high degree indeed. For famous pastors, even more so. The New Testament is crystal clear on this point. “Not many of you should become teachers, my brothers, for you know that we who teach will be judged with greater strictness” (James 3:1). When a pastor falls into sin, he does not merely sin against his victim and/or his family. He sins against the countless multitude of those who counted on him to represent the truth and love of God to them.

When I was eighteen, our youth pastor sexually violated a member of our youth group, a crime for which he was later tried and is now serving time.1 After the fact, it slowly became clear, as is often the case, that this was not an isolated event. But before his downfall, there was hardly a person in our community on whom he didn’t have a significantly positive impact. I was one of those people. He was a remarkably talented leader, who taught and showed me the character of God. As you might imagine, the fallout was immense, not just for those directly victimized by his actions (his victims, his wife and family, and those to whom he directly lied), but to all under his spiritual authority and care. The list of those in our community who deserted their faith after the incident is long, and includes many close friends of mine. Some gave up more than just their faith. In the years following, I remember one particularly common response among those who remained in the church (in fact, I hear it still today whenever leaders fail): “Christians put their trust in Jesus, not in other people. People will always let you down. If you lose your faith over an incident like this, you probably didn’t have much faith to begin with.” It sounds reasonable enough. The trouble is, the Bible paints a different picture…

Christ is our High Priest, but he is not the only priest. We are his body in the world. Through him, our role as priests has been restored. Thus very imperfect Peter is told he will be the rock on which Jesus builds his church. The disciples are told they will do even greater works than he with the help of his Spirit which he will send. Such priests are not masters, of course. They are stewards. But stewards represent the Master, for better or worse, and are therefore held to higher account than common servants, as Jesus’s parables reveal with graphic detail. But why? Why double down on the priesthood of believers, when they have done nothing but fail? Given the obvious hypocrisy and failure of the “stewards” of his day, the scribes and Pharisees, it would seem much more reasonable for Jesus to do away with the need to trust anyone but him: “No more hierarchies! No more spiritual leaders! I am the one and only king and priest!” But, strange as it may seem, he does not do this. The hierarchy remains. Stewardship remains. Jesus sends out the Twelve with the authority to bind and unbind, to make disciples, teach his commandments, and baptize. In the Epistles, the specialized roles and qualifications of church leaders are discussed in detail, and church members are told to “respect those who…are over you in the Lord and esteem them very highly” (1 Thessalonians 5:12-13). The kingdom of God is the remarriage of trust and trustworthiness, not only between God and his people but among his people. At every level of human existence, from the lowest to the highest, trust is our currency, our food, our drink, our oxygen. If it is trustworthy, we live. If it is poisoned, we die. There is no third option in which we do not trust.

At the beginning of Matthew 18, Jesus calls a small child to himself and declares, “Truly I tell you, unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven. And whoever takes the lowly position of this child is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven” (vv. 3b-4). This is one of Jesus’s more famous sayings, but it is rare that we hear it in the greater context of what comes immediately afterward: “If anyone causes one of these little ones—those who believe in me—to stumble, it would be better for them to have a large millstone hung around their neck and to be drowned in the depths of the sea” (v. 6).

Why the harsh transition? The answer is simple enough.

In the first saying, Jesus insists that there is no other way to enter into his kingdom than by means of radical, uncomfortable, childlike trust. This childlikeness is apparently required of all disciples. But then he changes perspective, forcing the very same audience to imagine themselves as the adults who welcome those children in. He says, in effect, “Now that you know what kind of trust is required–and that there is no other way into my kingdom–imagine the horror if that trust is not met with trustworthiness. We can perhaps more easily imagine this sort of horror on a physical level: the mother who abandons her infant or the father who sexually abuses his child. But the same problem of trust and trustworthiness scales all the way up to the spiritual. And when that trust is broken, well, heed the words of Christ. When pastors break the trust of their congregations–and for that matter when fathers and mothers and teachers and leaders of any kind fall into sin–it is not merely a “moral failure;” it is a relational failure and a spiritual failure. In such cases, it is still possible to make amends and rebuild trust. But we must begin by acknowledging the true depth and scope of what was broken. For which of you, desiring to rebuild a house, does not first sit down and count the cost?

For what it’s worth, Carl Lentz is also from my hometown. I did not choose his case arbitrarily. Though his scandal was based in NYC, it was and is heavily felt by many in our immediate community. My apologies to those for whom this re-opens a sore wound.

"He could say it, because grace is the power to keep promises, not merely—not even fundamentally—the ability to be excused when we do not."

I love this section. A good friend of mine told me once about this priest who would repeat the prayer "Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me a sinner," to himself non-stop (I'm pretty sure it was a fictional story, but still very compelling). So I too have began doing so not even understanding what I was saying, but knowing it needed to be said. Had I need for mercy because of how greatly I was sinning before those moments of prayer? Maybe, but I think now I understand that prayer more. It is not always "Have mercy on me because I just sinned and need your blood to cleanse me," though that may be true. I think now I say it and mean "Have mercy, Lord, that I may walk in your ways right now when I am given this choice to do so."

Mercy and grace to do the right thing, not just to be made right after doing the wrong thing.

Thanks again Ross!

Theologians like to think that it's bad theology which damages the church, but the truth is much more uncomfortable -- sexual sin and broken trust empties the pews and tarnishes the name of Christ ever so much more than any misplaced line of theology.

It boggles my mind that men such as Lentz are ever allowed to exercise authority again, or at least, so quickly after their public sins are made known. They should sit quietly in the pew with their brothers and sisters for decades as they allow God's grace to work in their lives before anyone asks them to lead others again.