The Future Of Our Churches

A Parish Manifesto (Abridged)

A longer version of this piece, entitled A Parish Manifesto, was published online in the theological journal Mere Orthodoxy. Please go there for the full experience (though, for many of you, I’m sure the abridged version will be not only sufficient but preferred!). Or, if you prefer to listen, see the podcast link below.

A Parish Manifesto (Abridged Version)

Two Streams: Holiness & Inclusion

Two central streams run throughout the Bible in seemingly opposite directions: holiness (“set apart”) and inclusion (“bringing in”). In Christ, these two streams most climactically flow together. Yet, in the history of the church, it has proven difficult to keep them together, to maintain “high walls and open gates,” as Wayne Meeks put it.1 Instead, we tend to let the pendulum swing. Thus, contemporary Christian debates regarding sexual ethics, heaven and hell, how to read the Bible, etc, tend toward a “holiness versus inclusion” paradigm, where conservatives argue for some form of holiness and liberals for some form of inclusion. The basic problem with this paradigm, though, is that if your God is all about inclusion, what are people being included into if not holiness? Likewise, if your God is all about holiness, who then can enter in? Thankfully, the Scriptures do not force us to choose one way or the other. The Bible is the story of the patient reconciliation of opposites.

And yet…

The “both-and” solution, while true in the abstract, does not always solve the problem on the ground. Yes, we must always hold both streams together. But certain moments require certain emphases, a la Ecclesiastes: “there is a time for this and a time for that.” Prophetic discernment may call us to choose one good at the seeming expense of another, but one good is never truly at the expense of another in the end. An act of mercy may seem to dispense with justice, yet mercy is also just. The calls of Nehemiah and Jeremiah were in opposite directions. One honored God by returning and rebuilding Jerusalem; the other by settling down in a foreign, unholy land. Both were right and would have been wrong to do the opposite in their moment.

Two Movements: Joseph & Moses

An even more fundamental example of this phenomenon is the juxtaposition between the stories of Joseph at the end of Genesis and Moses at the beginning of Exodus.

Joseph, the favorite son of Jacob, is sold into slavery in a foreign land by his murderous brothers. However, during his Egyptian exile, God seems to bless everything Joseph touches. Thanks to his wisdom and ability to interpret dreams, Joseph overcomes extreme trials and winds up being the right hand man of Pharaoh himself. When a famine strikes the land, he not only saves Egypt, but also saves his own starving people who venture into the foreign land in search of food. Joseph’s union to a foreign nation—as well as his marital union to a foreign wife, the daughter of an Egyptian priest—blesses the foreign nation and the people of God. The exclamation point on this “Joseph Movement” is when, near the very end of Genesis, his father Jacob literally pronounces a blessing on the pharaoh himself.

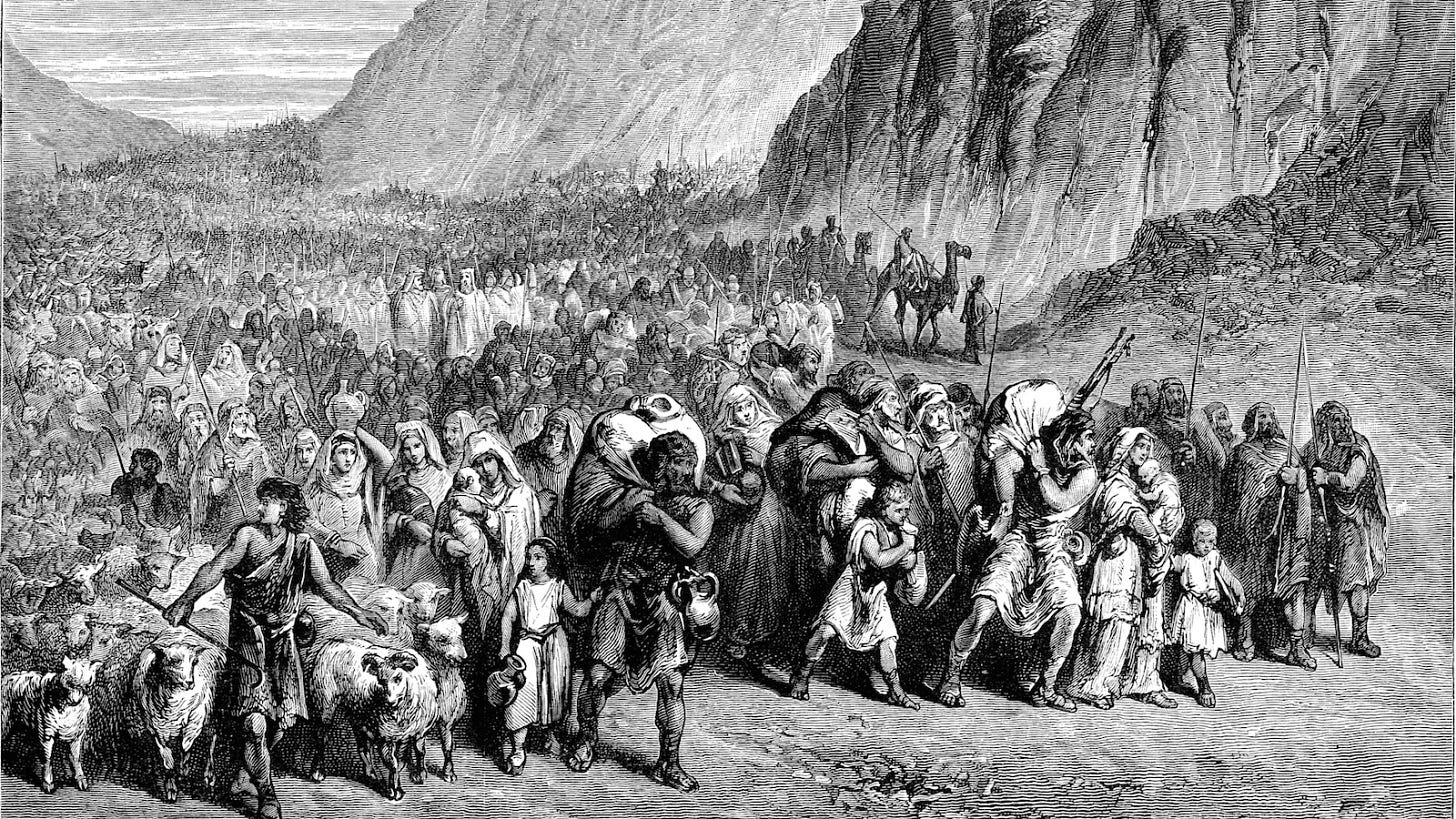

However, by the time we reach the opening chapter of Exodus, something has drastically changed. The people of God have become slaves in Egypt, and the new Pharaoh is calling for the killing of every newborn Hebrew boy. This is no proof that the Joseph Movement was unwise or mistaken. Again, the Joseph movement was unquestionably blessed. And yet, now the blessing has reached its saturation point. “Now there arose a new king over Egypt, who did not know Joseph” (Exodus 1:8). The moment is ripe for a new movement of God. Enter Moses, who must lead the people out of Egypt through the wilderness back to the holy land.

Now, don’t get me wrong. The Joseph movement is not all about inclusion, nor is the Moses movement all about holiness. The whole reason Joseph is continually blessed among foreigners is because, much like Daniel, he remains holy. Likewise, though Moses’s exodus is primarily a holy movement away from Egypt, he actually includes with him a ragtag “mixed multitude” of refugees, many of whom are not even descendants of Abraham. Both Joseph and Moses are holy and inclusive. But their different emphases in different seasons still matter. Joseph’s family blessed Egypt and was blessed by Egypt, no doubt. But if you end up with Moses in the wilderness saying, “Let’s go back to the blessings of Egypt!” (Ex. 16; Num. 14) you’re the problem, not the solution.

Now we come to the point.

It Is Time For A Moses Movement

Without going into great detail, I believe the 20th Century in America experienced the blessing of a Joseph Movement. What we now know as the “Evangelicalism” reached a climax with men like Billy Graham, who not only filled stadiums and TV screens across the country, bearing the fruit of millions of conversions, but also sat at the right hand of literal Presidents. I believe this was the blessing of God. We have this phenomenon to thank for the conversions of many of our parents and grandparents, whether in a Billy Graham crusade or a Young Life meeting. In fact, most of my own friends met the Lord outside of the walls of the church in ministries like Young Life. This is perhaps why many of our contemporary churches look and feel more like Young Life meetings than traditional worship services.

To be clear, I am not calling the modern Evangelical movement into question. As with any movement, I’m sure we could retrospectively poke holes in it if we chose to do so. I believe that would be a waste of time and possibly an inappropriate exposure of our spiritual fathers and mothers. My purpose, rather, is to propose that the current American Evangelical Movement, which was and is a Joseph Movement, a movement of inclusion toward an unholy world, has reached a saturation point. It is time for a Moses Movement.

Again, I am in no way proposing that we throw out “inclusion” for the sake of “holiness.” Engaging the culture is a good thing. We should invite the unchurched in. But if we are not a holy people, what are we inviting them into? “Come as you are,” is the modern Evangelical gospel at its core. And it will always be a valid gospel invitation, especially in a Joseph Movement. But it is not the only gospel invitation. There is also, “If anyone would come after me, he must deny himself, pick up his cross daily, and follow me.” Normally, of course, we save this latter invitation for later, or as the case may be, never bring it up at all.

Strange as it may sound, I believe we are now living in a moment where outsiders might actually prefer to be asked to pick up their crosses rather than merely come as they are. In a moment absolutely rife with mental health crises, meaning crises, identity crises, broken marriages, substance addictions, online addictions, and deaths of despair, people do not so much want to be “welcomed as they are” as shown what they could be. They actually want a truth that demands something of them. The modern individualistic, consumeristic cocktail of social media, Netflix, and Amazon has exhausted and enslaved us all, and we’re starting to notice. Only mention you’re leaving Egypt, and the modern mixed multitude will grab their jackets and meet you at the door. The best evangelism today is…holiness. But how do we become a holy church? In what follows, I propose four characteristics of a future, holy church:

1. Parishes

Our churches should be neighborhood-based, encouraging people to re-embody their faith, worship, and obedience where they live, alongside their actual neighbors.

A parish is an old word for a neighborhood (Gk. paroikos, “to dwell beside”), particularly a neighborhood under the care of a priest or minister. In recent years, certain technologies, most notably the car and the internet, have transformed our relationship to our neighborhoods. First, the car has given us options well beyond our own locality. This has been very powerful, but it has also tricked us into becoming consumers of our “favorite” church experiences rather than long-game participants in our given community. As a result, many Evangelical church members have lost the sense of generational loyalty, legacy, and commitment that comes with a long-term tie to a particular place. An odd proof of this can be witnessed in the increasing transformation of churchyards into larger parking lots. In the 1990s, the grassy fields next to many of our churches were often used by neighborhood kids for pickup ball games. In the 1890s, the same sorts of fields were used to bury the members of the church when they died. Ballfields are for communities. Graveyards are for generations-long communities. Larger parking lots…are for customers.

What the car began, the internet completed. Before the pandemic, half-empty megachurch parking lots were already a familiar sight. Simulcast sermons on large screens in satellite campuses and in living rooms(!) were already a common notion. During the pandemic, we turned this up to 11, hiring “online pastors” for our “online communities.” Evangelical churches have worked hard to seem more “relevant” and “accommodating” to the outside world. But many of our churches are now in danger of becoming disembodied imitations of community, shaped more by individual consumer preferences, programs, and personalities than by love of God and neighbor. What is more, the demons of our culture are winning. Deconstruction, mental illness, and divorce within the church are at an all-time high. Christians spend their days in increasingly abstract, meaningless jobs and increasingly lonely home lives. They spend their nights on Netflix and Instagram. Broadcast sermons, professional sound systems, and topnotch childcare during the service are not even beginning to solve these issues. And our constant attempts to evangelize outsiders betray a blindness to the gaping wound within. The Evangelical church must address the plank in its own eye. And that plank is…that we are failing to be the body of God to one another. The church must be re-embodied in neighborhoods so that it may once again enact the love of God through the love of neighbor.

2. Steeples

Our churches should be beautiful, holy places that point heavenward with beautiful, holy rhythms, that point heavenward. They should be set apart from the structures and rhythms of the secular world.

For well over a thousand years, Christian churches were built in the central high places of European villages, and church steeples were (and often still are!) the highest, most visible points. When the earliest European settlers arrived in America, they continued the tradition. Churches, rather than government buildings or marketplaces, actually marked the center of town. Just as church buildings gave visible shape to a village, church bells governed its rhythms, not only on Sunday but throughout the week. Church bells reminded believers when to pray, when to worship, when to celebrate, and when to mourn. They announced the weddings and funerals of one’s actual neighbors.

Near the end of mainline ascendancy, many faithful Christians began to be concerned that churches were becoming whitewashed tombs, museums filled only with the formal remembrances of a dead—or, at least, dying—faith. The steeples, bells, organs, stained glass windows, priestly vestments and liturgical recitations continued to hold a central place, but without their central meaning. They had become only form without content, sacrifices without love (Hos. 6:6). The early Evangelical response to this problem was to breathe spiritual life back into a dying body. The long-term effect, however, was to swing the pendulum from “form without content” to “content without form.”

Rather than continuing to breathe new spiritual life into a dying body, we replaced body with spirit. We replaced a pagan religion of earth with a Gnostic religion of heaven. Steeples, bells, windows, vestments, and liturgies were seen as the disease itself, rather than diseased body parts in need of a cure. The result has been a contemporary church movement fueled by “gospel content” without gospel embodiment. Depressed, anxious, porn-addicted believers gather anonymously in darkly-lit movie-theater-concert-halls where they’re fed passionate songs and sermons about how to “be saved.” But the rhythms on the ground do not change. We are orbiting beings. We cannot stop orbiting. If the church will not give us a new orbit, we will continue our old addictive patterns, however inspired and informed we might feel by the gospel content we download each Sunday.

We need new forms.

Perhaps our churches do not need literal steeples, bells, stained glass windows, and graveyards. But they do need to re-marry gospel form to gospel content. And that form must be holy and distinctive. It must set us apart. Our churches should be little glimpses of the marriage of heaven and earth in the world. They should be places of beauty and silence, of prayer and fasting, of mourning and dancing. They should not be places where we partake in the same paradigms and economies as the world, except with a Christian veneer. Steeples and bells are images for what, in the past, has set churches apart from the rest of secular society, both because they are distinctive and because they are beautiful. Steeples and bells draw the eyes and ears of everyone upward. That is what our church communities must do.

3. Priests

Our churches must be led by priests, un-busy holy people, who represent God to the people and the people to God.

The word “priest” is not looked upon highly by most Evangelicals today. To be clear, the term itself is really just an Englishization of the New Testament Greek word presbyteros, which meant “elder” or church leader. But in today’s parlance it tends to have a fancier, higher-church connotation, perhaps closer to the Latin “pontifex,” literally “bridge builder,” which finds its origin in the very ancient understanding of the priest as a kind of bridge between God and the people. Right away, one can imagine how such a concept could be problematic. Can we not commune with God ourselves? Must a human priest be the arbiter and mediator of my personal relationship with God? In short, yes. And Jesus our great High Priest has become that mediator.

Wonderful! Then we no longer have to rely on imperfect and broken people to lead us to God! Well, yes and no. Yes, Jesus is our ultimate bridge to God. But the way Jesus has chosen to administer that bridge in the world is…through other believers. Thus very imperfect Peter is told he will be the rock on which the church is founded. A priest is a steward, not the master. But a steward’s role is very important. He represents the Master (for better or worse) and is held more accountable than the common servant.

Because of the hypocrisy of the religious institutions we see in the Gospel accounts, it is tempting to think that Jesus came to do away with all human hierarchies and institutions (especially religious ones), to declare himself the one and only Priest-King and everyone else his equal servants. But the New Testament bears witness to another way. The hierarchy remains. Stewardship remains. Jesus sends out the Twelve with the authority to bind and unbind, to make disciples, teach his commandments, and baptize. Likewise, in the Epistles, the specialized roles and qualifications of church leaders are discussed repeatedly.

But aren’t all believers considered priests (e.g. 1 Pet. 2:9, Rev. 5:10)? Yes. But there are more and less helpful ways of interpreting the “priesthood of all believers.” The less helpful way is to insist that all believers are priests in exactly the same way by virtue of the fact that all believe in the same Lord (i.e. one King, equal servants). This is true in a sense, but also, in the family of God, we have different (and unequal!) roles. As in an ordinary family, fathers are not the same as sons, though sons may become fathers if, first, they are fathered. Doing away with family roles because all individuals within the family are “of equal value before God” would be nonsense. How could children survive without submitting to the authority of parents, almost as though they were God to them, for a time? Likewise, if all are priests in the exact same way, then none are priests at all.

Welcome to our moment.

If the modern Evangelical church has been largely stripped of its metaphorical steeples, so too, modern priests have been stripped of their metaphorical (and actual) vestments. The average Evangelical pastor wears common clothes and tends to reiterate his equality with the rest of the congregation. His role is no more special than yours. “I’m just like you,” is the basic sentiment from the stage (and notice, it is usually a stage, not a pulpit or an altar).

Of course, in a sense, our leaders are just like us. This makes it easier for church attendants to “come as they are.” But it also makes it easier for attendants to treat leaders as common providers of consumer services…services which, from a secular economic perspective, can often be found with much higher quality and consistency elsewhere. Thus our constant moving from church to church, or even from church to some other more polished and professional secular offering. We do not answer to the pastor. He answers to us. We are the customer, and the customer is always right.

Our Evangelical spiritual leaders are in a moment of identity crisis. Are they supposed to be CEO’s or local shepherds? Professional teachers and entertainers or exhorters of the local body? Professional counselors or religious authorities? Are they meant to be as busy as common secular workers or to be more available for the problems and needs that arise in the community? When they speak on Sundays, they are expected to speak as hyper-public prophets of God. When they cheat on their wives, they are expected to respond as hyper-private individuals, “just like you and me,” who “make mistakes” and “would ask for privacy in this time of healing.” The current Evangelical model—or lack of a model—for spiritual leaders is not working. Yes, there is a risk in calling imperfect people to become our set-apart authorities. They may fail, which will cost us dearly. But the cost of not doing so is already too much to bear.

In summary, our spiritual leaders must be exactly that: spiritual leaders, not mere staff members, busily employed with the various programs demanded by the church organization’s clientele. Pastors should be “priests,” whether we call them that or not. They should represent God to the people and the people to God. Despite our independent, egalitarian American sensibilities, the occupation of the butcher and baker are not “just as sacred” as the role of the priest or pastor. There is such a thing as a higher calling, and it does, as the writers of the New Testament constantly remind us, afford higher responsibility and accountability. “Not many of you should become teachers, my brothers, for you know that we who teach will be judged with greater strictness” (Jam. 3:1). This does not discount “the priesthood of all believers,” as we shall see in point #4. But the church must be led. Fathers and mothers do not say to their children, “Do not follow me; follow God.” As long as their children are children, the two commands are one in the same. “Imitate me as I imitate Christ,” says Paul to the Corinthians. When Moses was called by God to lead Israel out of Egypt, he was told that he would be “as God” to them. Something like this is still true in the church today. Jesus is our High Priest, but we are also called to submit to Jesus in others. If we do not, we will inevitably find ourselves submitting to the “priests” and spirits of false gods. Everyone submits, whether they wish to or not. The question is to whom.

Therefore, the task of our spiritual leaders is as difficult as it is irreplaceable. Though they are not God, they are called to embody him in the world, so that we can embody him in the world with their help, instruction, correction, and example. Pastors and priests should introduce and administer holy rites and rhythms, which unite and set apart the community of God from the world. Rather than being busy with programs and church growth strategies, they should be available for prayer and counseling throughout the week. They should be well-trained and highly qualified, though not necessarily impressive. They should be people of prayer, humility, and integrity who administer the sacraments faithfully and who shepherd their communities with discernment. They should be accountable to “bishops” above them and aided by lay ministers below them. Which brings us to our final point…

4. People

Ultimately, the church is not a building or a worship service. It does not have steeples. The church is the people of God. And though the family of God must indeed have “priests”—special, holy, trustworthy leaders to whom we all submit—at the same time, all believers are called to be priests. The church is for the making of a holy people, the body of Christ in the world. It must be constantly transforming attendants into worshippers and worshippers into ministers.

For too long, the modern church has simply accepted that most of its congregants will have their daily routines, their “secular liturgies,” entirely decided by the world, not only by the internet and the entertainment industry, but by their very jobs. Even professions which were invented or defined by the church for a millennium or more—“soul care” jobs such as social workers, professional counselors, child educators, even artists—have been co-opted and reshaped by the secular world. This might have been forgivable if such careers were still sustainable and effective today, but they are (very often) not. In part, this is because they have been divorced from the holy, communal framework in which human souls were meant to thrive and heal.

I am not proposing that the church become a conglomerate of businesses. The other way around. I am proposing that the church could once again be the originator and administrator of a sustainable, mutually-beneficial economy that does not center on money (though money may be involved) but rather on love of neighbor. In my small Methodist church on Hatteras Island (which boasts a 250 year old congregation), the first 20 minutes of the church service is taken up with the sharing of “joys, concerns, and needs” of the community. Action steps are decided in real time. This part of the service is often as long or longer than the sermon. This is what I’m talking about.

Perhaps not immediately, and perhaps not on the national level, but on the neighborhood level, the church can again be a driver of culture. The church can help to reconnect people to one another, to their place, and to their calling. The church has always done this. We can do it afresh right now. What if the inheritance of our grandchildren was a holy church?

Thank you, John Dickson, for giving me this phrase. John says he took in from Wayne Meeks’ masterful book The First Urban Christians.

I like the article Ross, and agree with many of your points. Regarding point 3, I wonder if the 'professionalisation' of priests/pastors is part of the problem too. You say they must be highly educated, but I'm not so sure. In my experience, the pastors who have best reflected what you describe are those without (or with very little) formal theological training. Maybe because this leaves them more humble and dependent on God and Holy Spirit? Maybe because they haven't be told what to think about certain issues? I don't know. There was obviously no such thing as Bible College for the early apostles, their authority was from God/Jesus/Holy Spirit and they could lead because of the way they lived out their loyalty to Jesus, not because of a certain amount of training.

I'm not sure if that makes sense? What do you think?

Your point about education being co-opted by the secular world put words to something I have been thinking as a future educator! People are flooding out of the profession because it takes a Christian worldview to delight in a child and discipline them, to offer unconditional care and unconditional push toward academic excellence. The people leaving and citing impossible standards are right. The care of even one little soul is too much responsibility! That’s another reason for the necessity of a Christian worldview: I can only pour so much out for the kids because the Spirit pours into me, I can only hold them because I am held by the Father, I can only sacrifice for them because the Son is on the cross for me. (Note: if only I could think like this in the moment. Instead I am nearly pulling my hair out because child A is arguing with child B about a spot in line for the third. time. today. while child C is rolling around on the floor 😭)