The Cosmic Middleman

On Moving Mountains, Part 2

Welcome to Part 2 of “On Moving Mountains,” an exploration of Jesus’s teaching on faith, dominion, and the impossible. If you haven’t read Part 1, here’s a quick synopsis:

Why did Jesus say we could move mountains if seemingly no one can move mountains? What kind of faith can do such things? In quantitative terms, we’re told no more than a mustard seed will suffice. But what of the quality of such faith? I propose the quality is that of authority, not to be confused with power. Authoritative faith speaks to the rock rather than striking it. Jesus does not overpower the storm, but tells it to be still. Whereas power ignores or diminishes the agency of the other, proper authority restores and redeems agency by calling the other—be it a person, a demon, a storm, or a mountain—to submit to that which is higher.

This, I believe, is our calling. Just as the world was made by speech—by call and response, not cause and effect—the world must be remade in like fashion. And human beings were meant to be not only subjects of, but participants in, that remaking. Authority is a lost art in our time. (Picture St. Francis asking the birds to stop singing so he can finish his sermon.) I don’t claim it will be easy to recover, but if we could, perhaps we could still move mountains with a word.

Intro: Why Authority Matters

In Part 1, I drew a distinction between power and authority and suggested that Christ’s ministry amounted to the reclamation of Adam’s authoritative dominion on behalf of the human race. In other words, the Word became flesh, so that you could move mountains.

In Part 2, I hope to show why this matters. If our sins have been forgiven and our “relationship with God” has been restored, what does it matter whether we regain authority over creation? Most of us just want to be “saved.” That is enough. We don’t care to be in charge of anything.

But this, Jesus says, will not do. Sin has left us not only alienated from God but from the world around us and from our priestly role on behalf of that world. We have fallen out of right relationship with our surroundings, and all creation is suffering because of it. The solution, Jesus says, is faith, which brings reintegration not only of ourselves but of the cosmos through us.

So…what is faith exactly?

Dominion and Imago Dei

Then God said, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness. And let them have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.” (Genesis 1:26)

I am not one to have pet peeves, not because I am such a good person, but mostly because I am woefully unobservant of my immediate surroundings (which is actually one of my wife’s pet peeves about me). But one pet peeve I do have has to do with the way Christian academics tend to use the term imago dei. And no, it’s not because I find their use of Latin pretentious. I like Latin; it’s pretty. It’s because I believe that most of our declarations of “being made in the image of God” are missing the point.

Today the phrase imago dei is typically used to highlight the inherent value and rights of every human being. And of course, I agree with their main point. But it’s half a point at best, like a prince who is always ready to remind you of his royal rights, but conveniently quiet when it comes to his royal responsibilities. I believe we’ve put the cart before the horse, and in doing so, we’ve actually diminished our view of human worth rather than adding to it.

The first question the Bible answers about human beings, when it tells us that we are made in the image of God, is not “What is our value?” but “What is our role?” That is to say, the prince can indeed be confident of his worth…once he understands his purpose. Purpose precedes value. Purpose is the ground of value. What we find in Genesis 1 is that to be made in the image of God is to be given a purpose like his, a priestly role and responsibility over creation that mirrors his own. This is what sets us apart from the rest of the created order; this is what gives us authority over Nature and, at the same time, what makes us subservient to her. (“For the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve.”)

As Christians, we have become accustomed to believing that true faith means something like the humility of “helpless dependence.” And I don’t deny that that is where it must often begin. But the prince who abdicates his throne because he deems himself helplessly unfit for office only feigns humility. For the truly humble prince, the throne symbolizes not so much his fittedness as his function, which he can no more abdicate than his own body and blood, however unfit he may feel to uphold it. For him, the key question is not so simple as, “Can I do it?” (No, you can’t.) The question is rather, “How can I do what is impossible for me to do, yet which I nevertheless must do, because it is my role and my destiny?”

This is the predicament in which the human race finds itself after the fall. This is why the covenants, the law, the temple, and the prophets all point not merely to our personal/individual forgiveness and redemption, but to the full restoration of the cosmos under God through human beings. And the New Testament doubles down on this point. Why else would St. Paul declare, even after Christ has come and died and conquered Death, that all creation groans in eager expectation—not only for Christ’s return, but for what?—for the sons of God to be revealed (Romans 8:19). For nothing less than the restoration of Adam’s dominion.

It will trouble no small amount of Christian souls to hear this—languishing as we are in the aftermath of a thousand failures of authority—but we are most like our Maker when we are reigning. “Do you not know that we will judge angels?” We were made for thrones and crowns and, dare I say, glory. The fact that we now covet, steal, and kill for the high position that would otherwise be ours by inheritance does not change the fact that creation still waits for us to assume that position rightly.

And yes, when finally we receive our crowns from him, there will be nothing better to do with them than to throw them back down at his feet. But that is precisely my point. Crowns were made for service. Again, even the Son of Man came not to be served, but to serve. That is his glory. That is what makes him Lord of all.

In what follows, I hope to show the relationship between faith, salvation, and dominion, in particular the reinstatement of imago dei. It is by grace you have been saved, through faith. But this is not so much a formula as a portal into new creation, the newness of which we are only beginning to taste and see.

For instance, if it is true that we are saved through faith, what can it mean that Jesus tells us that even a mustard seed of this faith can command mountains? Do we possess this mustard seed? Can we move mountains? No? Who then can be saved? “With man this is impossible, but with God all things are possible [in us!].”

Jesus’s promise about mountain-moving was neither arbitrary nor hyperbolic. Nor, as I have said already, is it an extra-powerful sign of an extra-zealous faith. On the contrary, as we will see, mountain-moving is a picture of what faith is meant to do and to be.

Recovering the Lock: Salvation as Restoration

For truly, I say to you, if you have faith like a grain of mustard seed, you will say to this mountain, ‘Move from here to there,’ and it will move, and nothing will be impossible for you. (Matthew 17:20)

Like most of Jesus’s teachings, I take the above saying to be, first and foremost, more of a riddle than a straightforward statement of fact. That doesn’t mean it isn’t also a fact. But it’s a riddle first, a riddle waiting to become a fact. Jesus’s words must first be seen as a problem before they can become a solution. Once a problem is well-understood, the solution is usually not long in coming. Sometimes our problems are self-evident. The bleeding woman wants to stop her bleeding. The blind man wants to see. Their needs are clear. They ask, and they receive. But no one, it would seem, needs to move a mountain. So why bring it up? That is the riddle.

Riddles are questions that make us ask more questions so that, eventually, we arrive at deeper answers. Good riddles unsettle us from the false contentment of automated solutions to problems we have hardly begun to consider. With such riddles, Jesus opened the spiritual eyes of his earliest disciples, and, in my view, the same teachings can still open the eyes of the church today, if we have ears to hear.

As Jesus often warned, the best way to stop up your ears is to believe you already have the answer. For modern-day evangelicals like myself, ironically, the claim that, “All answers are found in Christ,” can be one such ear-stopper. For certain, “All answers are found in Christ.” But what good is an answer to a question you haven’t even thought to ask? The problem for many Christians in our moment is not that we lack the key—Jesus is the Key, of course—but rather that we have lost the Lock.1 We don’t know how the Key works, much less what it opens. But the riddle of the mountain-mover shines a light once again on the Lock.

“Wait a minute,” you say. “We know the Lock. It is salvation from sin and death. That is what Jesus Christ opens for us, by the forgiveness of our sins.” And I don’t deny it. But the problem is even the word “salvation” has become for us an automated answer to a question we no longer know how to ask. There is, of course, nothing wrong with the word itself. “Salvation” is a glorious word. But like a key without a lock, it has begun to lose its meaning. No matter, it can be reclaimed.

In fact, in an attempt to reclaim it, let me suggest another word in its stead: “restoration.” Of course, this word too is imperfect. But notice how the word “restoration” appears to us slightly more in the shape of a question. “Restoration to what?” it seems to ask. Restoration to life? Yes. “Well,” you say, “this is exactly what is meant by salvation!”

Yes, but see, the question keeps on questioning: What is “life?” What exactly must be restored in order for life to be life? Is it mere biological function? “No, eternal life.” Exactly. But what is meant by eternal? Is it only a quantity? What is the quality of this “eternal life?” Again, what in particular must be restored? I reply: all that Adam lost. And what was he given in the first place? The answer to this question we have already shown, exactly as it is written in the very first scene of the Bible. But I warn you that you may not like the sound of it when I say it again:

Dominion. That is what Adam lost.

It is worth taking a moment to acknowledge the scandal, the stumbling block, we’re ushering in by choosing this word “dominion” as the telos of redemption. How about love, for instance? Restored relationship to God? Love is what Adam was made for, and love is what must be restored. Yes, in many ways, love is a far more pleasing answer than dominion.

And yet, once again, the problem with the word love is that it has lost so much of its meaning in use. It has been over-named and under-recognized. Perhaps even more than “salvation,” “love” has stopped being a mystery, a question, a lock, a portal. Like Christ himself, and like the salvation he came to bring, we have treated “love” as the obvious answer, as the golden key. And being overcertain of its value, we have lost and forgotten its purpose.

So I will insist, for now, on the word “dominion,” because it makes the questioner ask again: “Dominion over what?” “Dominion for what?” “How is dominion even good or loving or necessary?” To the last question, I answer that lordship may in fact be the highest form of love. (After all, “God is love,” is just another way of saying, “The Lord is love.”) But alas, we have all but lost the capacity to conceive of such a love. And so we must take the long road, rediscovering love through the lens of what seems almost its opposite.

Rediscovering The Key: Faith as Faithfulness

For truly, I say to you, if you have faith like a grain of mustard seed, you will say to this mountain, ‘Move from here to there,’ and it will move, and nothing will be impossible for you. (Matthew 17:20)

As long as we’re considering this teaching as a riddle, perhaps the heart of the riddle is the word “faith.” On the meaning of this word, everything else hinges. It is faith, Jesus says, that moves mountains. Okay, I believe. Why, then, won’t the mountains budge? Why won’t even my sore ankle budge? Again, what kind of faith can achieve such wonders? What even is faith? Well, how much time do you have? Just kidding. I’ll try to keep it brief.

The Greek word for faith in the New Testament (pistis) can be translated as both “faith” and “faithfulness.” In recent years, there have been great scholarly debates about whether Paul’s term pistis christou should be read as “faith in Christ” (as most of our Bibles have it) or “faithfulness of Christ.” Without entering the fray with regard to Paul’s intended meaning in each passage—there are great arguments on both sides—I take the ambiguousness of the term itself to be profoundly significant. For instance, are we justified by faith in Christ or by Christ’s faithfulness or (by extension) by Christ’s faith in the Father or by our faithfulness to Christ? To all this, the Christian can answer, “Yes.”

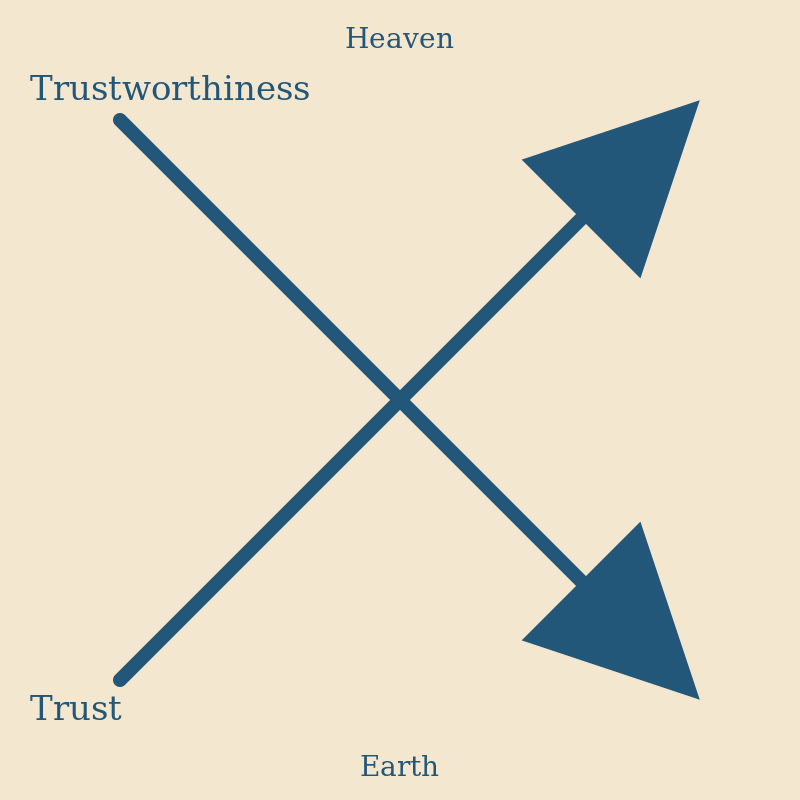

One way to appreciate the thickness of the biblical word faith is to incorporate both meanings simultaneously. Pistis, then, means something like faith-plus-faithfulness or trust-meets-trustworthiness, faithful faith and trustworthy trust, trust that proves itself able to be trusted.2 You may recall that in past essays, I have depicted Trustworthiness as a descending phenomenon, making the inaccessible meaning and certainty of heaven real and accessible on earth, and Trust as an ascending capacity to appreciate and count on the truth, beauty, goodness, or wholeness of a thing, despite its lack of certainty from our earthly vantage. Now, if that is the case, pistis can be understood as the center of the X, the faculty for discerning, inviting, and participating in the meeting of heaven and earth in our daily lives.

What I am saying is that the essence of pistis, not unlike its biblical counterpart agape (love), is found in its betweenness, in its inescapable relationality. You cannot merely “have trust;” you must trust in something, and that trust is continually tested by your trustworthiness to it. The degree to which you will count on, wait for, remain faithful to, and even reproduce the faithfulness of a person or thing shows whether you trust it or not. As C. S. Lewis puts it in Mere Christianity, “To have faith in Christ means, of course, trying to do all that He says. There would be no sense in saying you trusted a person if you would not take his advice.”

But notice that much of the “advice” we must take from Christ has to do with how we relate to others, especially to “the least of these.” The ultimate test of whether you have trusted your earthly father comes when you become a father or mother yourself. And this introduces a whole new level of betweenness.

Our trust in God is not merely offered up to him, but passed down to those who count on us in the form of trustworthiness. True biblical faith makes the Christian into a kind of cosmic middleman (or woman), mediating between God and nature as well as between God and others. As the New Testament declares over and over again, the faithful in Christ become ambassadors of Christ, not merely servants of the master, but stewards and overseers. We become priests, representing God to the world and simultaneously offering everything in the world back to God. The same faith which makes us dependent on Christ inevitably makes others dependent on us, requiring us to be like Christ to them. This is how reality works. And I am saying this is ALL part and parcel to what faith is.

Again, the way many of us talk about faith today, you would imagine that faith is literally all about dependence. You would think that Jesus told parables about servants who finally realized that they could do nothing at all but stop working and depend on the master’s good graces. “That is faith,” we say. But no, it isn’t. In fact, that’s literally what the wicked servant does in the Parable of the Talents. Meanwhile, the servants who multiplied their master’s wealth through risky-but-wise labor in his name are repeatedly called “faithful” (pistos).

That, then, is my functional definition of faith. Faith is the capacity to recognize and participate in reality by living constantly in the betweenness of trust and trustworthiness, ascending in trust to that which is trustworthy above you, and descending in trustworthiness to that which must trust you. And this betweenness—this priestly quality of faith, which makes us simultaneously servants and lords—also has a name in the Bible. It’s called (you guessed it)...dominion.

Lordship Redeemed

Then God said, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness. And let them have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.” (Genesis 1:26)

Two themes immediately stand out in the text: First, that humans were made in the image of God, and second, that they were given dominion over all other created things. That’s it. Those are the two themes. Moreover, the remaining verses of the chapter make this all the more clear by restating the same two themes multiple times:

So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them. And God blessed them. And God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it, and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over every living thing that moves on the earth.” (Genesis 1:27-28)

Finally, we return to my pet peeve. Hopefully now you can see more clearly that the immediate meaning of imago dei is found in our role much more than in our rights. As Christ is Lord of all, we were made lords of this earth. I don’t say it’s what I would have chosen—even the Psalmist is like, “When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers, what is man that you are mindful of him?”—but this, apparently, is the sort of project that interests our Maker. He is no clock-maker, and we are no cogs. He is a Father and a King, and we are his servants, his children, and the heirs of his kingdom.

Admittedly, the fall put a pretty big damper on all this dominion stuff. Outside the Garden, “thorns and thistles and the sweat of your brow” becomes the new normal. The earth still yields its fruit, but not without a fight, and not without claiming its own sort of victory in the end (“to dust you shall return”). As it turns out, when you’re not faithful to your Lord, it becomes much harder to maintain your own lordship.

And yet, the dominion mandate remains, even outside the Garden. The Lord restates it to Noah after the flood, yet with a foreboding addendum—“the fear and dread of you shall be upon every [living thing]”3—a phrase which casts no small amount of doubt on the purity and stability of sinful man’s dominion over anything. Much like the curses of the ground and the womb, man’s dominion has been cursed.

Once Adam ruled Nature by means of authority. Whatever he named the animals, that they were. His authority was true, and therefore good. His lordship was love. But now, there would be discontinuity between call and response, between speech and reality. If Adam’s rule was once based on a relationship of trust and trustworthiness—between himself and God and between the world and himself—now, at least for a time, it would be based on power and dread. If you want the mountains to move, the Lord seems to say to Noah, you will have to force them. And they will not go quietly.

As you probably know, the rest of the Old Testament bears witness to this corrupted dominion—to the ever widening gap between lordship and love. But it also hints again and again at its solution, finally revealed in the New Testament: the resurrection of man’s authority in the person of Jesus Christ.

All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go, therefore, and make disciples… (Matthew 28:18)

All authority has indeed been given to Christ, not to us. And yet, because Christ is our Representative, what is true for him becomes true for us, through faith. Faith is the trust-and-trustworthiness that links us to him, that makes his fate our fate. If he dies, we die. If he is raised, we are raised. And if he rules, we shall rule with him. But that same faith is also the link between him—his glory, his lordship, his love—and the rest of creation. For we are his Body in the world, and we represent him to the world as he represents us to the Father.4 And if we are his Body, then we speak with his voice. And even the mountains will hear us and be glad to obey.

Easier Said Than Done?

But of course there is still one glaring problem with all this talk of faith and dominion and authority and mountain-moving. And that is that the mountains still won’t move. You might have supposed that, in the course of my theological musings, I’ve forgotten this brutal fact. But no, it hangs over every word. It’s the elephant in the room. If Christ came to restore our authority over creation, if Jesus said that nothing would be impossible for those who believe—and we believe—why does the impossible remain impossible?

You might have noticed that the subtitle to this final section is a play on words. I admit, “Easier said than done,” is a fair rejoinder to my mountain-moving manifesto, thus far. “Talk all you like. Ain’t nobody moving any mountains.”

Fair enough. But to be clear, my claim (and Christ’s) is not that we can move mountains, but that we will speak to them, and they will move of their own accord. Which raises the question: Is it easier to speak to a mountain than to move it? Is it easier to operate by call-and-response or cause-and-effect? Well, that depends.

The entire Atlantic slave trade, it seems, operated according to the premise that coercion was more profitable than negotiation, that cause-and-effect trumps call-and-response. And at least in the short term, the slavers’ premise proved true. It was easier done than said.

Again, is it easier to ask someone to marry you or to force them at gun point? Well, if they don’t trust you and don’t want to have anything to do with you, I suppose force would be “easier” in the sense that, in that moment, it would be the only way. Of course, it would be a terrible idea for the same reasons that the slave-trade was a terrible idea.

But notice, I don’t just mean terrible on a moral level. Both are bad ideas, even for those in control, because both are doomed from the start. They are unsustainable relationships, requiring ever-new and more exhausting acts of coercion—and accruing ever-new forms of collateral damage—just to push off an inevitable and disastrous expiration date.

But let’s return to the marriage example. If you want to marry someone who doesn’t want to marry you, there is another option besides forcing what cannot be forced or despairing of what can never be at all. The other option is to be faithful. To spend however long it takes proving yourself trustworthy, keeping your promises, laying yourself down and pouring yourself out for the sake of your beloved, being willing and ready to get stomped on by the other in the process.

This, of course, has been God’s game plan all along with regard to his people. This is how proper authority works. The physics of true lordship is steadfast love. Nothing easy about it. But, again, he is patient. And when the day comes, when his call rings true in our hearts, he will only speak a word, and we will be his. It will be almost…easy.

What would it look like to be trustworthy to a mountain for long enough to change its mind, so that it wants to respond to your call? It might not be easy, though perhaps far easier than with a person. Perhaps a mountain only requires a mustard seed of faithfulness, whereas the human heart requires far more.

In any case, how can we begin to remake our lordship into love so that it can finally become true lordship? I have some ideas. Perhaps you do too? If so, leave a comment. And stay tuned for Part 3, where I (finally) begin to explore how mountain-moving might actually become possible for us.

If you enjoyed this post, please hit the LIKE and RESTACK buttons below. Thanks!

I noticed recently that the work of George MacDonald and the (more contemporary) work of Matthieu Pageau have almost perfect overlap regarding this point (and many others). Interestingly, when I asked Matthieu if he was familiar with MacDonald, he said he was not. Holy Spirit connections.

You could also say “dependence and allegiance.”

Genesis 9:2

See Jesus’s High-Priestly prayer in John 17 for a detailed description of this economy.

Babe, if you would simply feed him or take him for a walk every once in a while, the dog would probably listen to you.

I think it's N. T. Wright who talks about 'pistis' being understood as 'loyalty' which I've always liked as an active form of 'faith'. Am I being loyal to Jesus and God? Am I acting in the way a loyalty servant does?

Also makes me think of the loving servant with the pierced ear - the desire to choose to remain my lord's servant, not out of obligation but out of a deep love that causes me to want to serve him.