The Best of 2025

What I Read, Watched, & Listened To This Year

Merry Christmas Everyone!

Since 2016, my friend Thomas Dixon and I have shared our reading lists with one another at the end of each year. Over that time, I’ve slowly expanded my list to include my favorite essays, interviews, movies, and music. Besides being a good excuse to catch up with a friend, these lists have allowed us to cheat off of each other’s recommendations for future reading. I hope it will help you in similar fashion. Skip to the bottom for my absolute “Best of 2025.”

NOTE: These are not all works published this year; just things I read and listened to in the last twelve months (mostly listened to—I’m an audiobook person). Following Lewis’s advice, I tend to read old things and re-read the best things.

— Ross

P.S. Check out last year’s list for more recommendations.

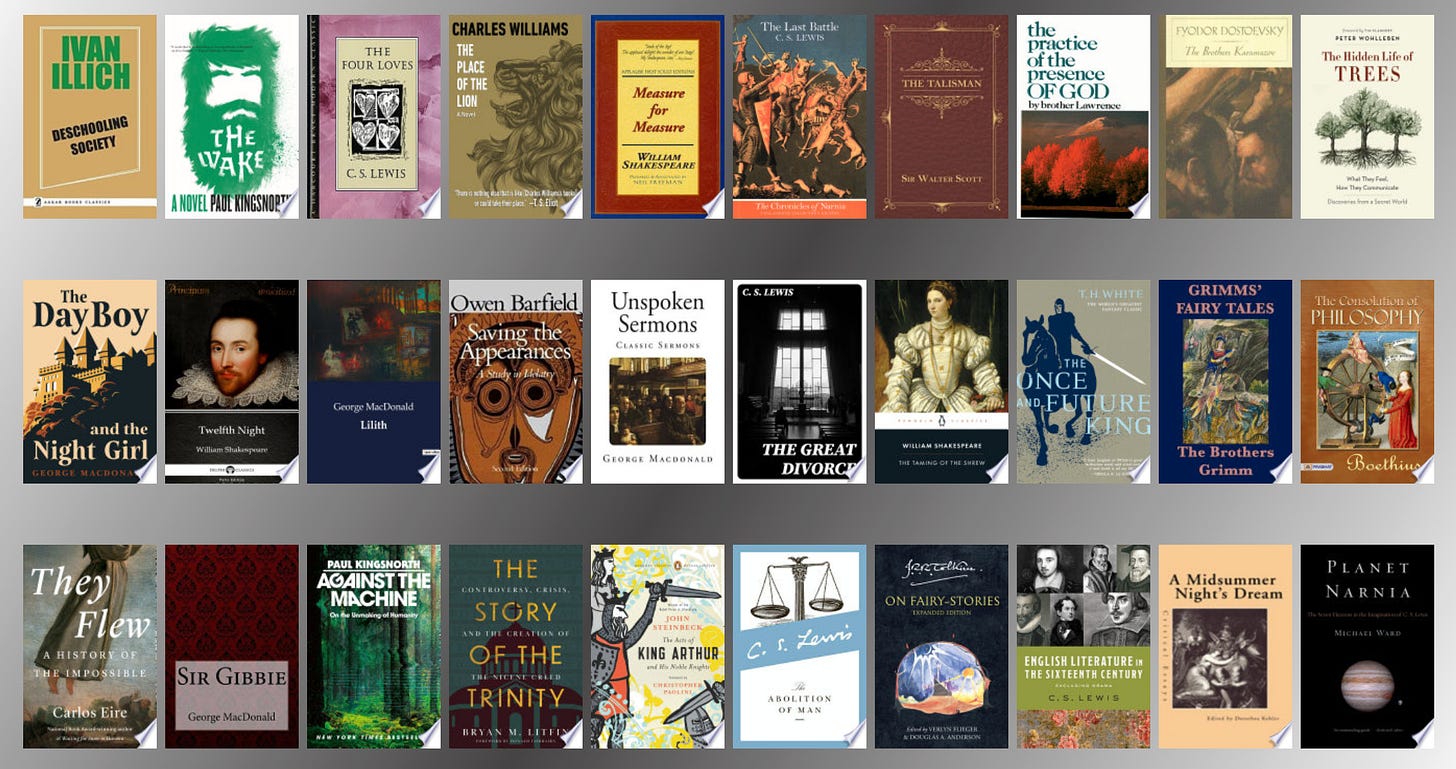

2025 Books I Read

Deschooling Society, Ivan Illich - rare that a work of nonfiction can wake me so thoroughly from my own philosophical slumber, but this book did; Illich’s thinking has more potential to radicalize me than most, so I have to be careful when reading him; DS is a glorious, prophetic, out-of-the-box take on our society, which made me think differently about many things without necessarily agreeing with the author on all those things; thus, my favorite kind of read; here’s a taste:

Since there is nothing desirable which has not been planned, the city child soon concludes that we will always be able to design an institution for our every want. He takes for granted the power of process to create value. Whether the goal is meeting a mate, integrating a neighborhood, or acquiring reading skills, it will be defined in such a way that its achievement can be engineered. The man who knows that nothing in demand is out of production soon expects that nothing produced can be out of demand. If a moon vehicle can be designed, so can the demand to go to the moon. Not to go where one can go would be subversive. It would unmask as folly the assumption that every satisfied demand entails the discovery of an even greater unsatisfied one. Such insight would stop progress. Not to produce what is possible would expose the law of ‘rising expectations’ as a euphemism for a growing frustration gap, which is the motor of a society built on the coproduction of services and increased demand. [...]

Man has developed the frustrating power to demand anything because he cannot visualize anything which an institution cannot do for him. Surrounded by all-powerful tools, man is reduced to a tool of his tools. Each of the institutions meant to exorcise one of the primeval evils has become a fail-safe, self-sealing coffin for man. Man is trapped in the boxes he makes to contain the ills Pandora allowed to escape. The blackout of reality in the smog produced by our tools has enveloped us. Quite suddenly we find ourselves in the darkness of our own trap.

The Four Loves, C. S. Lewis - thousandth read; could read it every year; maybe I just will.

The Wake, Paul Kingsnorth - a very dark novel; pretty masterful depiction of pre-modern perspective, for my money; but not exactly an enjoyable read; those who think Kingsnorth’s last couple of years raging against the modern machine is based on some kind of naive dream that “earlier times were better times” should read one of his novels; he may be a bit radical in his rejection of our present civilization, but he is also far from quixotic about the past.

The Last Battle, C. S. Lewis - people will say it’s not his best, that it’s sorta weird and he could have ended it stronger, etc; I say it’s wonderfully and fittingly weird, and I wouldn’t change a thing about it.

The Language of Creation, Matthieu Pageau - has become a yearly slow-read for me these last few years; I see new things all the time thanks to Matthieu’s symbolic perspective; possibly one of the most important theological books of the 21st Century (certainly the most important to me, but then again I don’t read much contemporary theology).

The Place of the Lion, Charles Williams - my favorite work of fiction this year; opened up an entirely new perspective through which to understand Lewis and the spiritual imagination of the Inklings; it was almost uncanny to learn that someone had basically already written a kind of That Hideous Strength before Lewis had even converted to the Christian faith; highly, highly recommend.

Planet Narnia, Michael Ward - re-read for a book club; I don’t have a high appreciation for much “Lewis scholarship” (other than the masterful work required to compile and publish his own original essays, letters and other unpublished works), but this book is a work of absolute genius; it has opened a door for me that no other book about Lewis or the Inklings—and I’ve read many—has. Forever grateful to Zach Kuenzli for recommending this one.

The Great Divorce, C. S. Lewis - I read it every other year with my surf camp staff (in a rotation with Screwtape Letters); never gets old.

The Talisman, Sir Walter Scott - first read; hard to stick with it at first, but then I was glued; sublime prose and a fascinating perspective on the relationship b/t Christianity and Islam in the time of the Crusades. Plus, things like this (a description of the knight Kenneth falling in love at first sight):

But to Kenneth, solitude and darkness, and the uncertainty of his mysterious situation were as nothing--he thought not of them--cared not for them--cared for nought in the world save the flitting vision which had just glided past him, and the tokens of her favour which she had bestowed. To grope on the floor for the buds which she had dropped--to press them to his lips, to his bosom, now alternately, now together--to rivet his lips to the cold stones on which, as near as he could judge, she had so lately stepped--to play all the extravagances which strong affection suggests and vindicates to those who yield themselves up to it, were but the tokens of passionate love common to all ages. But it was peculiar to the times of chivalry that, in his wildest rapture, the knight imagined of no attempt to follow or to trace the object of such romantic attachment; that he thought of her as of a deity, who, having deigned to show herself for an instant to her devoted worshipper, had again returned to the darkness of her sanctuary--or as an influential planet, which, having darted in some auspicious minute one favourable ray, wrapped itself again in its veil of mist. The motions of the lady of his love were to him those of a superior being, who was to move without watch or control, rejoice him by her appearance, or depress him by her absence, animate him by her kindness, or drive him to despair by her cruelty--all at her own free will, and without other importunity or remonstrance than that expressed by the most devoted services of the heart and sword of the champion, whose sole object in life was to fulfil her commands, and, by the splendour of his own achievements, to exalt her fame. Such were the rules of chivalry, and of the love which was its ruling principle.

Are you kidding me? In this light, I must insist once again on the greatest love song of our time:

The Practice of the Presence of God, Brother Lawrence - hadn’t read it since I was a teenager; a classic for a reason; actually a harder read than I recalled, which is odd since most classics are much easier for me in my 40’s than they were in my teens; it’s still beautifully simple, but it didn’t hold my attention the way it did the first time (maybe just me?):

Let us thus think often that our only business in this life is to please GOD, that perhaps all besides is but folly and vanity.

C. S. Lewis Essay Collection, C. S. Lewis - I finish it and then I start it over again; I don’t know why, but somehow it’s Lewis’s essays more than his fiction—and definitely more than his published non-fiction books—which really make me feel like I am getting to know the man and his perspective on things; hot take: if I could only have one book with his name on the front, it would be this one.

Twelfth Night, William Shakespeare - the first of my little summer trip through Bill’s most popular comedies; such a fun one; I thought about it for weeks afterward.

The Brothers Karamazov, Fyodor Dostoevsky - fourth(?) read; does it get any better than this?; still see new things in it; appreciated the story as a whole more this time around, whereas in the past I have felt it to be his least unified work, a kind of mosaic of stories and philosophical musings without a totally unified narrative; this time I saw the unity:

At some thoughts one stands perplexed, especially at the sight of men’s sin, and wonders whether one should use force or humble love. Always decide to use humble love. If you resolve on that once for all, you may subdue the whole world. Loving humility is marvelously strong, the strongest of all things, and there is nothing like it. (Father Zosima)

Measure for Measure, William Shakespeare - my new favorite play (h/t Zach Kuenzli again); I will resist the urge to tell you all the reasons here, but suffice it to say it is thoroughly Christian, deeply symbolic though also quite entertaining on its face; the biggest shocker for me was seeing afterward how many contemporary critics have completely missed its meaning thanks to their own cynical takes on gender, sexuality, and politics; honestly it’s a form of robbery; it made my apolitical self want to come out as stridently, dogmatically anti-woke just so college students could have a chance to appreciate Shakespeare again.

He who the sword of heaven will bear Should be as holy as severe, Pattern in himself to know, Grace to stand, and virtue go; More nor less to others paying Than by self-offenses weighing. Shame to him whose cruel striking Kills for faults of his own liking. Twice treble shame on Angelo, To weed my vice, and let his grow. O, what may man within him hide, Though angel on the outward side! (The Duke, Act 3, Scene 2)Saving The Appearances, Owen Barfield - this man is slowly transforming my epistemology; read at your own risk:

“Science, with the progressive disappearance of original participation, is losing its grip on any principle of unity pervading nature as a whole. The knowledge of nature—the hypothesis of chance—has already crept from the theory of evolution into the theory of the physical foundation of the Earth itself. But more serious, perhaps, than that, is the rapidly increasing fragmentation of science. There is no science of sciences, no unity of knowledge; there is only an accelerating increase in that pigeon-holed knowledge by individuals, of more and more about less and less.”

Unspoken Sermons, George Macdonald - reading these sermons years ago changed my life; reading them again felt like reading them for the first time; the man seems to have broken for himself the dim glass through which the rest of us see our Lord. Here’s a snapshot from ONE sermon, which I chose at random:

The liberty of the God that would have his creature free, is in contest with the slavery of the creature who would cut his own stem from his root that he might call it his own and love it…who poises himself on the tottering wall of his own being, instead of the rock on which that being is built. Such a one regards his own dominion over himself…as a freedom infinitely greater than the range of the universe of God’s being. If he says, ‘At least I have it my own way!’ I answer, You do not know what is your way and what is not. You know nothing of whence your impulses, your desires, your tendencies, your likings come. They may spring now from some chance, as of nerves diseased; now from some roar of a wandering bodiless devil; now from some infant hate in your heart; now from the greed or lawlessness of some ancestor you would be ashamed of if you knew him; or it may be now from some far-piercing chord of a heavenly orchestra: the moment it comes up into your consciousness, you call it your own way, and glory in it! (Series III, Chapter 5, “Freedom”)

Lilith, George Macdonald - possibly my favorite novel of all time, but every time I recommend to others, they tend to falter on the middle part (which is admittedly long and slow); this time, however, we read it as a book club and I think I was able to make many converts in the process; this book is a deep well; it’s like swimming around in a nightmare of death only to have it turn into the best dream you’ve ever had (and yes, it’s literally a story about death and sleep and dreams); I still feel I’ve hardly reached the bottom of it, but this read I went pretty deep.

“What does it all mean?” I said.

“A good question,” the Raven rejoined. “Nobody knows what anything is; a man can learn only what a thing means. Whether he does depends on the use he is making of it.”

“I’ve made no use of anything yet.”

“Not much, but you know the fact, and that is something. Most people take more than a lifetime to learn that they have learned nothing and done even less.”

Okay fine, one more:

[Mr. Vane:] “But surely I had no power to make [the Little Ones] grow.” [The Raven]: “You might have removed some of the hindrances to their growing.” “But what are they? I did think perhaps it was the want of water.” “Of course it is! They have none to cry with!” “I would gladly have kept them from requiring any for that purpose.” “No doubt you would—the aim of all stupid philanthropists! Why, Mr. Vane, but for the weeping in it, your world would never have become worth saving!”

Okay fine, one more more:

“We stood for a moment at the gate whence issued roaring the radiant river. I know not whence came the stones that fashioned it, but among them I saw the prototypes of all the gems I had loved on earth—far more beautiful than they, for these were living stones—such in which I saw, not the intent alone, but the intender too; not the idea alone, but the embodier present, the operant outsender: nothing in this kingdom was dead; nothing was mere; nothing only a thing.”

The Taming of the Shrew, William Shakespeare - not Bill’s most well-loved play and perhaps for good reason (though it did give rise to one of my wife’s favorite movies, Ten Things I Hate About You); weird but still enjoyable, with plenty of gems like this:

Why are our bodies soft and weak and smooth, Unapt to toil and trouble in the world, But that our soft conditions and our hearts Should well agree with our external parts? – Katherina, Act 5, Scene 1A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare - probably most people’s first experience of Shakespeare (it was for me and for my kids, who had to act it out with their homeschool co-op a few years back; deserves its premier place.

The Once And Future King, T. H. White - super fun read; my son also enjoyed it; but I could see why the Inklings didn’t love it; a modern, casual, humorous adaptation of the Arthurian stories that’s not casual and humorous enough to be Monty Python and yet somehow too casual and humorous to feel like you’ve really entered the world of the legends themselves; not the way I would want the Arthurian stories to be introduced to my children (I’ll take Howard Pyle), but perhaps a nice light take on them for those already familiar; The Sword and the Stone by itself is still pretty magical though.

The Day Boy & The Night Girl, George Macdonald - somehow I didn’t even know this little gem existed until this year; a story about two children kidnapped and raised by a witch who only lets the boy live during daylight hours and only lets the girl be awake at night; besides being a great idea for a modern folk tale, it’s a brilliantly simple exploration of the mysteries of gender.

Grimm’s Fairy Tales, The Brothers Grimm - was pretty amazed at how readily my boys locked onto these stories compared to most things we read together; some of these stories are very weird–like a foreign language that you know means something but the meaning is veiled to you, we were sometimes tempted to think it was just narrative gibberish; other times the stories resonate for days or weeks; it’s a treasure trove for sure.

The Consolation of Philosophy, Boethius - as a Lewis aficionado, I’m embarrassed to say this was my first time reading the whole thing through; I loved it so much; can’t recommend highly enough:

Love, all-sovereign Love!—oh, then, Ye are blest, ye sons of men, If the love that rules the sky In your hearts is throned on high!

Sir Gibbie, George Macdonald - the man’s soul is miles deep; I cannot imagine not being amazed by him for the rest of my life; this tale—forgive me, I say this as a huge Dostoevsky fan—struck me as a more maturely Christian version of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot.

Alas for the human soul inhabiting a drink-fouled brain! It is a human soul still, and wretched in the midst of all that whisky can do for it. From the pit of hell it cries out. [...] There are sins which men must leave behind them, and sins which they must carry with them. Society scouts the drunkard because he is loathsome, and it matters nothing whether society be right or wrong, while it cherishes in its very bosom vices which are, to the God-born thing we call the soul, yet worse poisons. Drunkards and sinners, hard as it may be for them to enter into the kingdom of heaven, must yet be easier to save than the man whose position, reputation, money, engross his heart and his care, who seeks the praise of men and not the praise of God. When I am more of a Christian, I shall have learnt to be sorrier for the man whose end is money or social standing than for the drunkard.

Or this:

Having no natural bent to literature, but having in his youth studied for and practised at the Scotish bar [school of law], he had brought with him into the country a taste for certain kinds of dry reading, judged pre-eminently respectable: the history was mostly Scotish, or connected with Scotish affairs; the theology was entirely of the New England type of corrupted Calvinism, with which in Scotland they saddle the memory of great-souled, hard-hearted Calvin himself. Thoroughly respectable, and a little devout, Mr. Galbraith was a good deal more of a Scotchman than a Christian; growth was a doctrine unembodied in his creed; he turned from everything new, no matter how harmonious with the old, in freezing disapprobation; he recognized no element in God or nature which could not be reasoned about after the forms of the Scotch philosophy.

They Flew, Carlos M. N. Eire - hot take warning: I can’t remember a book which received such high praise from people I trust that fell so flat for me; not that the book was bad; don’t get me wrong: what it set out to do, it did excellently; as a historical accounting of some of the wildest miracles in the history of the church (mostly taking place at the dawn of modernity!), it’s an absolutely fascinating project, and the historical data seems carefully and thoughtfully put together; maybe this was just the moment in which I realized I don’t care for modern secular history; I wanted less lists and forensic corroborations of facts (I get it, lots of people flew) and more…meaning; I understand that we must still pretend that modern historians are not in the meaning business—other than to paint a picture of the philosophical and theological imaginary out of which these events supposedly took place—they’re “just giving the facts,” and I do actually appreciate an air of neutrality, but for my money, I wanted more; I don’t think this was any fault of the author, who seems a more brilliant man than I; I guess I just discovered that some people really care about facts more than I do and are less curious (or at least more humbly silent) than I about what such facts might imply about the world in which they supposedly occurred; it felt a little like those old apologetics books from the 90’s trying to give forensic proof of the resurrection of Christ; I can see how that could be a valid use of scholarship; perhaps 70% of my disappointment is just personal preference as to how to show the reality of a thing (for me, if the meaning of an event resonates and integrates with the rest of reality, I judge it as more trustworthy than merely if the scientific method has verified the available data), but again I admit this is mostly personal preference; the other 30% of my issue is perhaps more objective, and it has to do with the way people imagine we know things about the past: I take it as rather straightforward that the past is not present, and therefore that factual access to events that occurred before our time are not accessible to us in the same way; our access to the past, whether we like it or not, is facilitated almost entirely by means of narrative, that is, by means of past peoples’ presentation of facts not unfiltered—but necessarily filtered—through their meaning and their value structures, and requires us to dance to their tune (not our own) if we want to know them (archaeology is, of course, an exception to this rule, and yet is all the more in danger of anachronism since the “direct access” which it affords tends toward an overly confident approach, unknowingly filtering past facts directly through our present imaginary and then telling modern stories under the guise of revealing ancient truths); anyway, my over-criticism is probably mostly coming from the fact that, as I read this book, I was writing about the meaning of miracles myself, and felt the book to be stubbornly unwilling to converse with my particular interests, which is my problem, not the author’s, so take all this with a large grain of salt.

English Literature in the Sixteenth Century, C. S. Lewis - still haven’t quite finished it, but part of the reason for that is that the very long intro, “New Learning and New Ignorance,” which could be published as a book in itself, so captivated me on this reading that I read it FOUR times before continuing to the rest of the book; it’s a rich philosophical and theological exploration of the West’s slow turn to modernity:

Man with his new [scientific] powers became rich like Midas, but all that he touched had gone dead and cold.

The Hidden Life of Trees, Peter Wohlleben - not a big science guy, but I try to read at least one science book each year; this one blew my mind, and if you’re familiar with my “On Moving Mountains” series, you’ll see why:

In the symbiotic community of the forest, not only trees but also shrubs and grasses—and possibly all plant species— exchange information this way [by communicative networks of call-and-response]. However, when we step into farm fields, the vegetation becomes very quiet. Thanks to selective breeding, our cultivated plants have, for the most part, lost their ability to communicate above or below ground—you could say they are deaf and dumb—and therefore they are easy prey for insect pests. That is one reason why modern agriculture uses so many pesticides. Perhaps farmers can learn from the forests and breed a little more wildness back into their grain and potatoes so that they’ll be more talkative in the future.

As in the world of Prince Caspian’s Narnia, our once “talking” world has become deaf and dumb. But since it may have been our own spells that put it to sleep, perhaps we can also be the ones to wake the world to its former (and, more imporantly, future) glories.

Against the Machine, Paul Kingsnorth - most of you will have heard too much of this book already from other sources; I’ll just repeat what I have said before about Kingsnorth’s anti-civilization project: For those frustrated by Kingsnorth’s seeming all-or-nothing style, try to hear him prophetically, not strictly theologically. It may not be a categorical fact that civilization is always a sinful structure, that jellyfish tribes & Christian barbarians are always the way forward, but if, as I believe, we are passing from a Joseph Moment to a Moses Moment, Kingsnorth’s emphasis is appropriate and will prove even more true over time. Also, you gotta love this quote he drops from Chesterton:

The whole modern world has divided itself into conservatives and progressives. The business of progressives is to go on making mistakes. The business of conservatives is to prevent mistakes from being corrected.

The Story of the Trinity, Bryan M. Litfin - a great little beginner-level read on the history of the doctrine of the Trinity by an old professor of mine from UVA.

The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights, John Steinbeck - this was a gem I had no idea existed before a few months ago; bummer he never completely finished it; critical reviews, as I understand, were mixed, mostly lamenting the fact that he did very little new with the text other than clean up Malory’s archaic language for a younger/modern audience and add his own style and emphases to the narrative, but that’s exactly what I love about it; there are, in my opinion, too many “modern adaptations” of things which, lacking the humility of a translator (which is already a creative and interpretative work in itself), insist on making the original work better by asserting their own “improvements;” the irony here is of course that if anyone had the talent to create his own Arthurian world, it was Steinbeck; and yet he was humble enough not to do so; cheers to that; still quite Steinbeckian though, in its own way; a shame he didn’t finish it.

The Abolition of Man, C. S. Lewis - an almost yearly read; much of my recent essay series “On Moving Mountains” is in response to some of the loose threads left by this brilliant critique of our modern perspective on reality.

Waiting on the Word, Malcolm Guite - beautiful collection of Advent poems with just the right amount of commentary; I don’t care for commentary generally, but I find, with poetry, a good commentator really helps me love and appreciate every word more; Guite is that kind of commentator; plus he picks great poetry:

By God’s birth Our common birth is holy; birth Is all at Christmas time and wholly blest --- from “Christmas and Common Birth” by Anne RidlerOn Fairy Stories, J. R. R. Tolkien - fourth or fifth time reading; always opens new doors for me; if Lewis is the father of my thinking, Tolkien is the mysterious uncle who interjects a different style and perspective on the same truths at just the right times and in just the right ways:

The Gospels contain a fairy-story, or a story of a larger kind which embraces all the essence of fairy-stories… The Birth of Christ is the Eucatastrophe of Man’s history. The Resurrection is the Eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation. This story begins and ends in joy… There is no tale ever told that men would rather find was true, and none which so many skeptical men have accepted as true on its own merits… Art has been verified. God is the Lord, of angels, and of men—and of elves. Legend and History have met and fused. But in God’s kingdom the presence of the greatest does not depress the small. Redeemed Man is still man. Story, fantasy, still go on, and should go on. The Evangelium has not abrogated legends; it has hallowed them, especially the ‘happy ending’.

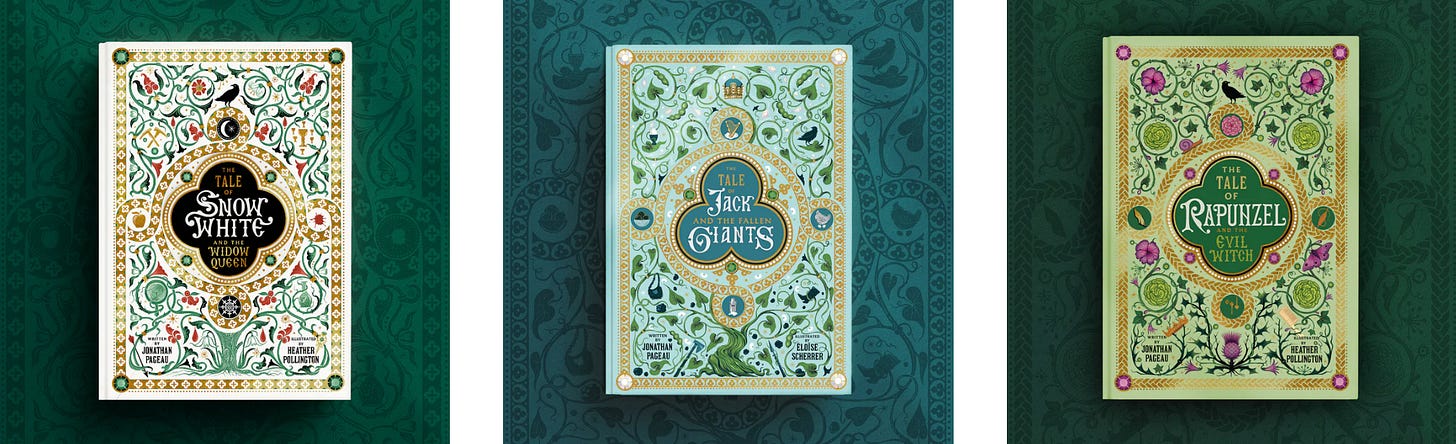

Jack and the Fallen Giants / Rapunzel and the Evil Witch, Jonathan Pageau - speaking of fairy tales…these are small books, so I thought I’d include them together; Pageau’s fairy tale series continues to amaze; I especially love Rapunzel, my favorite and, I think, the deepest so far; I’ll be teaching my students on it this Spring.

2025 Podcasts

Not a big year for me and podcasts…

“The Symbolic World,” Jonathan Pageau (most)

“Interesting Times,” Ross Douthat (most)

“The Rest Is History,” Tom Holland and Dominic Sandbrook (a few)

2025 Interviews, Courses, Essays, & Lectures

“Metacrisis: Interview with Jordan Hall,” by Pavel Schelin - brilliant discussion; this was the interview that became the backdrop for my own interview with Jordan a few weeks later entitled “The Divine Economy”

“Sexuality After Industrialism” by James Wood - my favorite essay of the year over at Mere Orthodoxy, reflections on Ivan Illich’s book Gender; I think I read it while I was writing “Partnership Over Compromise,” which turned out to be the most popular essay I’ve ever written on Substack.

“Feminism, the Body, and the Machine” by Wendell Berry - another (obviously much older) piece on the same subject matter: gender and the possibility of home-based economics in the post-industrial age; excellent from beginning to end.

“We Must Become Barbarians” by Paul Kingsnorth - this one blew my socks after; turned out to be one of the grand finale chapters to Kingsnorth’s aforementioned book Against the Machine, and rightly so; the notion of “cooked barbarians”—those living within the walls of the Empire, who pay their taxes, etc but nevertheless pay it little homage and have formed their own subtle village-style economy under its nose–-has stuck with me.

“Symbolism Masterclass,” a course by Jonathan Pageau - a work of absolute genius; I have said it before, but I think Jonathan Pageau (perhaps paired with his brother Matthieu) is the closest thing our generation has to a C. S. Lewis; he sees things that few others see and communicates them on a popular level in a way that few others can; I don’t think Pageau has been gifted with quite the same level of clarity in communication as Lewis, and it shows, especially in courses like this; it’s not as easy to follow as I was hoping, especially for the uninitiated—I’ve struggled for years to find the right way to share this man’s work with people who know nothing about him—but still…no one’s really doing what he’s doing; I thank God for this man.

“Tolkien & Universal History,” a course by Richard Rohlin - okay fine, Richard Rohlin is kind of doing what Pageau is doing; but he doing it with Pageau at Symbolic World, so yeah; Richard is another faithful genius, and this course was great for people like me who love Tolkien but don’t really “nerd out” to him like so many of his followers do; I learned a lot; highly recommend.

“Deeper Yet Into Creation and Renewal” an interview w/ Matthieu Pageau - had to throw something of Matthieu in here; still think “The Language of Renewal” is the most mind-blowing interview I’ve watched in a couple of years at least; looking forward to his next book; this interview is great too though!

“When A Heart Is Really Alive: George Macdonald and the Prophetic Imagination” by Malcolm Guite - a wonderful lecture by one of my favorite contemporary thinkers talking about one of my favorite writers of all time.

“Conversation of Michael Levin with Iain McGilchrist #2” - I mentioned I don’t read or follow much science, but I’ve been following both of these two quite closely, since both seem to have (certainly McGilchrist does have) a deep philosophy undergirding their science, which seems rare these days; this was a great conversation; both of these men’s work have informed my recent essay series, “On Moving Mountains”

“The Over-Diagnosis Crisis” w/ Dr. Suzanne O’Sullivan - another deep interest/concern of mine, tackled with admirable skill and nuance by Dr. O’Sullivan; glad to see a publication like Unherd having these kinds of conversations.

“Jordan Peterson vs. 20 Atheists” - okay, I wouldn’t say this was one of my favorite videos of the year, but it definitely made me think a lot; in general I think Christian critics were too hard on Peterson after this one; but that’s not all I think; you can read more of my thoughts here: “On Prophets & Their Demise”

“Brave New Biology” w/ Jonathan Pageau, Michael Levin, & John Vervaeke - man, this conversation was thrilling and terrifying; Levin confirms, through biological research, what so much of my theological explorations have posited about the difference between power and authority; as it turns out, even the cutting age of science is discovering the world is made primarily of “call-and-response,” not “cause-and-effect.”

2025 Music I Enjoyed

Alas, not a lot. Mostly just listened to Bach, Billy Joel and Fleet Foxes again. The new Jacob Collier was good, as usual. The new Taylor Swift not so much. Andy Squyres released a great little EP about marriage; he came and played it on our backyard, which was wonderful. And my friend William Sumner continues to write beautiful stuff like this.

2025 New (& Old) Movies & Shows I Watched

Severance (Season 2) - I don’t know; I loved the first season, but it just felt like the second season was far too slow getting to the punch line; whole episodes where hardly anything happened; they saved FAR too much for the final episode, but I admit that the final episode did not totally disappoint; I sort of hated it when I first watched it, but then Jonathan Pageau’s analysis helped me appreciate it more; did I feel like it wasted my time at times? yes; is it still the most original, most intelligent, and possibly deepest show on the internet right now? also yes.

The Minecraft Movie - was actually pretty fun for being an obviously not very good movie; I admit I just love Jack Black being Jack Black.

Mission Impossible: The Final Reckoning - not everyone liked this one, but I finished the series feeling grateful for what it had accomplished; definitely some cliche moments and less-than-profound messages baked in, but the main theme that stood out to me from the films, which was emphasized beautifully in the last, is this: Ethan Hunt is a man who refuses again and again to save the world at the expense of his friends and loved ones, a thing which his governmental superiors continue to fault him for. Is he seriously going to put the whole world at risk to save the person he loves…again? Yes, he is. You see, Ethan somehow understands the Christian paradox of love, which is this: to love your neighbor is to do your part in saving the world. Whereas to love the world despite your neighbor is to save neither. Because Ethan embodies this truth, his sacrificial actions (like those of Christ) not only save his loved ones, they really do save the world. Moreover, his actions (like Christ’s) inspire others to sacrifice themselves with him, which in turn saves and redeems the world even more. It’s almost like Tom Cruise has been reading Dostoevsky…or the Bible. Or maybe not. Either way, the films are haunted with this paradoxical truth, just as our civilization is still haunted with the Christ we have tried so hard to leave behind.

Fountain of Youth - pleasantly surprising National-Treasure-style good-humored adventure flick, directed by Guy Ritchie, starring John Krasinki and Natalie Portman (what could go wrong); honestly, really the only thing that went wrong was that the ending was a bit intense and over-bearing, sort of along the lines of people’s faces melting off in Raiders of the Lost Ark; not enough wisdom or experience or creativity to know how to depict spiritual danger.

Stick (Season 1) - first season was really enjoyable; Owen Wilson seems like he kinda plays himself and I’m all for it; not as good as Season 1 of Ted Lasso, but a nice effort in that direction.

The Waltons - it was a Waltons year for our family; maybe my favorite show we’ve ever watched as a family; the script-writing is formulaic, but in the best way; no problem presented is every easily or tritely solved; life is complex, even when it is simple; the line between good and evil runs straight through the human heart, and yet, through suffering, perseverance and love, good does seem to triumph again and again; highly recommend.

30 Rock - I don’t know why, but this show still makes me laugh more than almost any other; interpret that as you will; I’m not particularly proud of it, just being honest.

The Big Short - re-watched this one on a plane with my wife last week; can’t remember watching something with such clever writing and story-telling; not sure if it’s underrated, but man, I forgot how good it was.

Ready Player One - hadn’t seen it before; the whole family really enjoyed it, though we were definitely rooting for the whole virtual world to be destroyed at the end; nevertheless, exceeded expectations.

Master & Commander - took some convincing to get the whole family to watch this with me, and though there were some grisly parts, everyone enjoyed it; and for me, it was just as much of a masterpiece of writing, acting, and directing as I remembered.

What did I miss? I really want to watch the new Frankenstein and the new Knives Out. A good friend also told me to watch Train Dreams. Those are the three on my list for the new year.

Ross’s Best of 2025:

Best Classic Fiction I Read: Lilith, George MacDonald (1895)

Best Contemporary-ish Fiction I Read: The Place of the Lion, Charles Williams (1931)

Best Non-Fiction I Read: The Hidden Life of Trees, Peter Wohlleben (2016)

Best Show or Movie I Saw: Severance, Season 2 (2025)

Ross’s Best of 2024 (for the record):

Best Classic Fiction I Read: Phantastes, George MacDonald (1858)

Best Contemporary Fiction I Read: The Name of the Rose, Umberto Eco (1986)

Best Non-Fiction I Read: Poetic Diction, Owen Barfield (1928)

Best Show I Watched: Dark Matter (2024)

Ross’s Best of 2023 (for the record)

Best Classic Fiction I Read: Robin Hood, Louis Rhead (1910)

Best Contemporary Fiction I Read: Hannah Coulter, Wendell Berry (2004)

Best Non-Fiction I Read: Remaking The World, Andrew Wilson (2023)

Best Film I Saw: Oppenheimer, Christopher Nolan (2023)

Ross’s Best of 2022 (for the record)

Best Classic Fiction I Read: East of Eden, John Steinbeck (1952)

Best Contemporary Fiction I Read: Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell, Susanna Clarke (2004)

Best Non-Fiction I Read: Seeing Like A State, James C. Scott (1998)

Best Film I Saw: Pig, with Nicolas Cage (technically 2021)

That’s it! Please share your own “Best of 2025” in the Comments. I’d love to know hwat I missed. Merry Christmas & Happy New Year!

I’m crushed by your take on ‘They Flew,’ as we seem to have very similar taste and I was just gifted that book for Christmas. Great list though!

Barfield was a genius. He changed the way I see the world.