On Moving Mountains

Why Miracles Are Not What We Think

Friends,

Earlier today, I put out a note saying I was just about finished with a massive 15,000 word essay (small book?) on Jesus’s teaching about moving mountains. I asked if I should post it all at once, break it up into 3 or 4 smaller essays, or quit writing altogether until I can learn to write shorter. The overwhelming majority vote was to release it in parts (thank you for not telling me to quit). So, without further ado, here is Part 1. Please leave your honest thoughts and questions in the comments, as it will help me to improve future sections before they come out.

O LORD, our Lord, how majestic is your name in all the earth! You have set your glory above the heavens. Out of the mouth of babies and infants, you have established strength because of your foes, to still the enemy and the avenger. When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars, which you have set in place, what is man that you are mindful of him, and the son of man that you care for him? Yet you have made him a little lower than the heavenly beings and crowned him with glory and honor. You have given him dominion over the works of your hands; you have put all things under his feet, all sheep and oxen, and also the beasts of the field, the birds of the heavens, and the fish of the sea, whatever passes along the paths of the seas. O LORD, our Lord, how majestic is your name in all the earth! (Psalm 8, ESV)Man’s conquest of Nature turns out, in the moment of its consummation, to be Nature’s conquest of Man. (C. S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man)

Preface

Every so often I’m reminded that Jesus said things I don’t actually believe. Yes, I am a Christian, and I do believe everything Jesus said. But also, I am a Christian, and I don’t believe everything Jesus said, at least not fully, not yet. Here is a saying I’m only now beginning to believe:

For truly, I say to you, if you have faith like a grain of mustard seed, you will say to this mountain, ‘Move from here to there,’ and it will move, and nothing will be impossible for you. (Matthew 17:20)

I know what you’re thinking: “He’s a Christian. Shouldn’t he just believe all this supernatural stuff? Jesus did all kinds of miracles. So did his disciples. The whole faith rests on a man being raised from the dead, but moving a mountain is too much?”

Sure, but I know what you’re also thinking: “Wait a minute. He said he’s beginning to believe that people can move mountains. Like, literal mountains? Because as far as I know, no one has ever moved a mountain. Not even Jesus moved a mountain! He can’t actually believe that. Queue the predictable sermonic metaphor: ‘Life’s obstacles are the real mountains, etc, etc.’”

Now, hopefully, you’re with me. Both sides of you: the part that believes and the part that doesn’t. And don’t worry, I promise to spare you the metaphors. When I say I’m beginning to believe we can move mountains, I mean nothing less than literal mountains. I admit my faith in this regard is small, perhaps much smaller than a mustard seed. But if it only takes a mustard seed to move a mountain, perhaps it only takes a microbe to believe that a mustard seed can move a mountain. I think I may have found that microbe, and I’d like to share it with you here. After all, microbes can become mustard seeds, and mustard seeds can do more than move mountains: they can become the largest tree in the garden.

Buried Treasure

In the opening quotations, you may have noticed a rather stark juxtaposition. While the Psalmist wonders at God’s decision to give human beings (even infants!) dominion over creation, C. S. Lewis laments the effects of this apparent dominion. To whatever degree modern man believes he has outsmarted or overpowered nature, Lewis says, the truth is the reverse. Even and especially in our hyper-technical age, nature is having the last laugh. And of course this feels exponentially more true today than eighty-some years ago when Lewis wrote it. The algorithms we’ve built to solve all our problems are creating for us an even deeper problem, enslaving us not to the army of evil robots we might have feared, but to our own appetites, which we haven’t feared nearly enough.1 Yet Lewis wasn’t questioning the wisdom of the Psalmist or the wisdom of God revealed therein. He was rather prodding us to reconsider what our “dominion” over creation is meant to look like, since our current version isn’t exactly panning out as we might have hoped.

In this essay series, I intend to pick up where Lewis left off. I hope to show that our true dominion, which we must and shall regain, is not our conquest or power over Nature, as the sorcerers and technologists would have it, but rather our authority over her. Hidden in the subtle dilemma between striking the rock (power) and speaking to it (authority) we find our true purpose and the key to our redemption. Jesus’s images of his disciples telling mountains to move and trees to be uprooted and thrown into the sea are not extra-powerful signs of an extra-zealous faith, but simple signs—mustard seeds, in fact—of what true faith has always entailed: the reclamation of Adam’s authoritative dominion under God.

Of course, to modern ears, this distinction between power and authority will hardly register, since to us almost everything is power.

In the modern world, dominion means domination. Presidents and policemen can be said to have authority only to the degree to which they have the power to enforce it. As D. C. Schindler has pointed out, when Nietzsche declared that God was dead, he was probably speaking of authority in particular. Nietzsche’s “will to power” is a response to a world increasingly bereft of authority—that unseen relational principle by which laws and morals, kings and priests were established and trusted—while, at the same time, gaining incredible new powers.

Why is God dead? How did we kill him? It wasn’t simply by thinking secular thoughts. Nietzsche was living in the midst of a new scientific/mechanized age, where Bacon’s dream of overcoming nature with technological power was finally coming true on multiple fronts. The fairies and gods and spirits and angels of the Middle Ages were fading in the new light of man and his machines. Humans had become the only agentic beings in the universe. In this new mechanized view of the cosmos, everything else in creation became not so much subject to us—as it might have been in the Garden—but objects to be moved as we see fit. Those who did not recognize this shift, thought Nietzsche, were doomed to be slaves. Those who did recognize it could replace the gods.

Even if Nietzsche were overstating his case, even if authority had not been altogether killed by the new powers of scientific progress, it had at least been buried alive. Yet, not far beneath Nietzsche’s feet—and ours—lay a treasure which, if unearthed, might tempt us to sell all the powers of his industrial age and our digital age combined. This is the treasure which Jesus called “the kingdom of heaven.” We might also call it “the dominion of God” or, more broadly, “the love of God” or even “the gospel.” But for our present purposes, I will call it authority.

If Nietzsche had been right about the burial of authority, he was certainly wrong not to sell everything he had to gain the land it was buried on. Christianity is that land, and we who claim to be its inheritors in an age of unprecedented power would be fools not to start digging for what we’ve lost. Sleepers, awake! Mountains can still be moved with a word. At least, so I am beginning to believe.

The Ring of Authority

Crises of authority are not new. Nietzsche’s generation was not the first to wonder if the authority of God was finally giving way to the raw power of man. In Jesus’s time, the Roman Empire was Exhibit A for this line of reasoning. Even the Jewish religious leaders of the day seemed to operate not as stewards of God’s true authority but as cynical power brokers (“They honor me with their lips, but their hearts are far from me”). You have heard of a power vacuum. Let me introduce you to an authority vacuum. The people of God were living in one then, just as we are living in one now. This is why both Matthew and Mark record the same shocked response from the crowds after hearing Jesus preach for the first time:

The people were amazed at his teaching, because he taught them as one who had authority, not as the teachers of the law. (Mark 1:22, Matthew 7:28-29)

Jesus’s ministry marked the return of proper authority. But it was not only people who awaited the final filling of the authority vacuum:

For we know that the whole creation has been groaning together in the pains of childbirth until now. [...] For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the sons of God. (Romans 8:22, 18)

How can the sun and moon groan? How can the trees wait? How can the birds eagerly long for the revealing of the sons of God? The foundation for this strange, agentic view of creation is laid in Genesis 1.

Contrary to the modern scientific vision, the creation account does not tell of a world of inanimate objects being zapped into existence and moved around by force. As I have spelled out in more detail elsewhere, God did not create mere objects, but agents, choosers, lovers with the capacity to hear and obey his commands. After all, he made the world by speaking (“Let there be light”). The creation narrative is absolutely full of commands, not only to human beings but to everything. God is no clock-maker. The sun and the moon are not so much “set in motion” as assigned their own proper jobs and jurisdictions over the day and the night. The birds and the fish are told to be fruitful and multiply. All created things reflect the likeness of God in at least this way: that all have the capacity for relationship with him, the capacity to respond to his word, the capacity to obey.

What I am saying is that God brought the world into being not by an act of power, but by an act of authority. He spoke, and reality obeyed his voice. And at the climax of this narrative, human beings are given the crowning glory of being made in his image. Like the rest of creation, we were made with the capacity to know and love and obey our Maker. But unlike the rest of creation, we were also given the capacity to speak to them as He had done. We alone were given authority to rule over creation just as He would rule over us. But, of course, the story takes a turn.

Imagine (bear with me here) a kind of brighter parallel to Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, except instead of Sauron forging the one Ring of Power by which he meant to enslave all the races of Middle Earth, God gave to Adam and Eve a “ring of authority” by which they were meant to lead and guide the created order into further and deeper levels of love and faith and glory. But the treasure of man’s authority was lost. Sure, the stories of the Old Testament tell of those few and fleeting moments in which the treasure seemed to have been recovered, then lost again. But the New Testament comes with good news. The ministry of Jesus Christ is the definitive unearthing of the primordial treasure of authority, the climactic proof that true dominion is something far more beautiful and powerful than mere domination.

Just as the world was made by speech—by call and response, not cause and effect—the world would be remade in like fashion.

In the Gospels, Jesus speaks, and not only the crowds but the whole created order seems slowly to awaken from its long agentic slumber. Jesus’s teachings and his miracles in the Gospel accounts appear haphazardly mixed, because they are inextricably linked: two parts of the same authoritative action. Even his miracles tend to be speech-acts. It’s easy to miss, but next time you open one of the Gospels, watch for this and you will see: Like his Father in the beginning, Jesus does not merely act upon things. He commands them, and they obey. He is, after all, the Word of God, which was with God in the beginning. Through him all things were made. And so, when he comes to earth, he speaks, not only to men and women, but to demons and fevers, to storms and trees, to blind eyes and paralyzed bodies. He speaks to things which human beings would not normally dream of speaking to. And in their submission to his authority, they reclaim their own true health and power. Whereas raw power tends to ignore or diminish the agency of the other, proper authority restores and redeems agency by calling the other to submit to that which is higher.

This is why, by the way, all atheist arguments that begin with, “If God is all-powerful and all-loving (blah-blah-blah)…” are misguided. Simply put, God is not all-powerful in the sense they imagine. If he were, the world would have been set right long ago. But God’s primary means of making and moving and redeeming the world is authority, not power. Straight-line power has always been the “easy fix” according to His opponents. Just ask the devil in the desert: “Turn these stones to bread.” “Throw yourself from the pinnacle of the temple and let your angels catch you.” “Rule all the kingdoms of the earth; only bow down to me.” In that final temptation, we find that even Satan understands the primary place of authority over power much better than those who argue on his behalf. “Go ahead, rule everything,” he says, “as long as you answer to me.”

Every ruler bows to someone or something. Power always proceeds from some greater authority. Ironically, the most powerful people are often the least aware of this fact. They cannot see whom they serve until it’s far too late.2 And lest we be tempted to point the finger up the political or economic hierarchy, today the same can be said of every smart-phone user. The technological powers we continue to accrue and depend upon have hidden authority structures behind them, which are not advertised (nor even mentioned in the fine print), because not even their makers are fully aware of them. But lose your phone for a mere twelve hours, and you will discover beyond a shadow of a doubt that these are not “neutral tools” we carry around in our pockets.

Remember when God gave Moses the power to do signs and wonders in Pharaoh’s court, and, as it turned out, Pharaoh’s own magicians could do many of the same things? That must have been very disconcerting for Moses. But today we find ourselves in a similar situation, except worse: the modern tech-magicians produce the signs and wonders, and the faithful are left wondering if God can match their power. Sure, he can. But frustratingly, he often won’t. We pray for power, for results here and now. But if we’re honest, he doesn’t often prove himself to be the genie we’d hoped for. And so, rather than continue to ask and trust and wait as he taught us (Luke 18:1-8), we pray instead to our phones and computers, to experts, procedures, chemicals, and contracts.

We pray directly to the powers which give us what we want when we want it. And in doing so, we slowly forget the true shape of reality. We forget that God does not play that kind of game. We forget that the most important and meaningful things in our lives, even in an earthly sense—our loves, our longings, our purposes, and our peace—operate according to a subtler physics, which we lost the ability to recognize as soon as we lost the patience to wait for it. We forget that even the modern devices to which we constantly submit our requests, have other subtler masters, which become our masters to the extent that we depend upon them. And we forget, perhaps most of all, that we were made to master these masters.

Speaking To The Rock

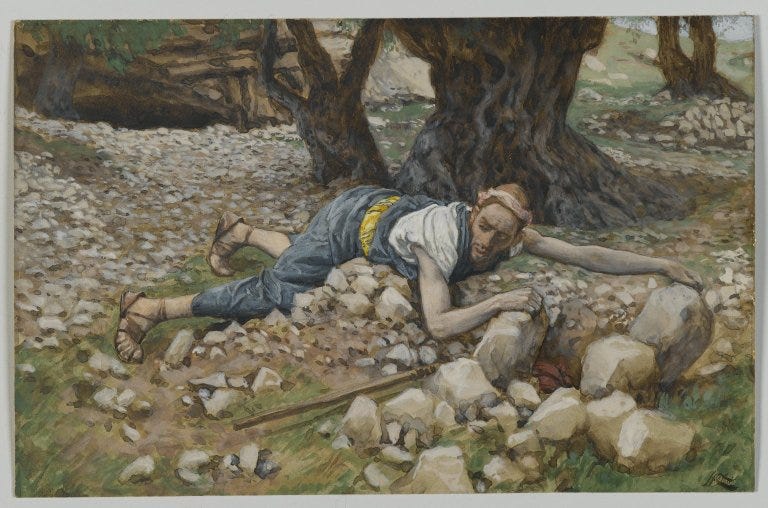

The difference between Moses and the court magicians—even if Moses himself could not see it—was not primarily a difference in power, but in authority, not in what they could do, but in whose name they were doing it. This is the key to understanding much of the Exodus narrative. Egypt may have had chariots, but they did not have the Name of God. And this is what made Moses’s sin of striking the rock so consequential. Yes, on an earlier occasion, God had indeed permitted Moses to strike the rock. After all, God hadn’t shied away from acts of power in delivering his people from Pharaoh’s hand. But you can tell very early in the story that such acts were a last resort (or, from another perspective, a first step).

God’s purpose was never to form a people around his power, submitting to divine power if only to be able to wield it for themselves. That would make them no different than Egypt. No, the Lord had another plan. His second command to Moses about the rock—that he should speak to it rather than striking it—was a further and deeper iteration of the first, moving from the clear and physical boon of divine power to a subtler relationship of trust in divine authority. To the extent that Moses could submit to divine authority, he would begin to embody that authority himself, like a new Adam, naming and commanding created things to do his bidding (e.g. telling the rock to produce water). To the extent that he would not, even the power he had would be lost. “For to everyone who has will more be given, and he will have an abundance. But from the one who has not, even what he has will be taken away” (Matthew 25:29). Power without authority is like a pair of good lungs under water.

But why tell Moses to strike the rock first, then change the command? Why not tell him to speak to it the first time? Well, for the same reason that Jesus stopped the woman’s bleeding and healed the man’s blindness before he stopped the bleeding of our souls and healed the blindness of our hearts. God is patient. The former requires only a word from him; the latter requires, among other things, a word from us. And he will woo us to speak that word by whatever means necessary. Power must sometimes come before authority, in our eyes, so that authority can finally come before power in our hearts. Or, to put it another way, God is in the business of turning microbes into mustard seeds, one interaction at a time.

In this light, the story of Abraham takes much the same shape as that of Moses. Small steps of faith early on lead to great experiences of power and promise. And yet all this leads where? To the altar upon which Abraham is commanded to sacrifice the son of that promise. For both Abraham and Moses, God presents the opportunity to convert power to authority by means of sacrifice. Now, for an infinitely deeper version of the same pattern, consider that in 1 Corinthians 10 Paul identifies the Rock which Moses struck as Christ himself. I can hardly begin to plumb the depths of what this suggests, but here’s a start: Just as the rock at Meribah becomes the stumbling stone that condemns Moses while also saving the people, Christ the Cornerstone becomes the stumbling stone that condemns—but also saves—us. Our “striking him” for the sake of signs and wonders should have led to our speaking to him for the sake of repentance and relationship, but instead our feeble and faithless attempts to speak to him led to our striking him to death. And yet, irony of ironies, while proper power couldn’t give way to proper authority, the very height of improper power nevertheless gave way to proper authority: by means of his crucifixion, we now proclaim him Lord of all. Yet still, if striking the Rock does not finally give way to speaking to Him, we may be struck by the Rock and crushed (Matthew 21:44).

Note that the relationship between power and authority in Scripture (and in life) is complex. It is not so straightforward as power:bad, authority:good. The point is not to replace the ways of the earth with the ways of the heavens. The earth is the body of the heavens just as heaven is the breath of the earth. In all of God’s redemptive acts, he is marrying heaven and earth by calling earthly things to submit to heavenly patterns. After all, even earthly things—from microbes to mustard seeds—already have the invisible patterns of heaven built in, whether they know it or not. The physics of earth (cause-and-effect) and the physics of heaven (call-and-response) both have their place, but if cause-and-effect does not submit to call-and-response, it will simply undo itself over time. “Dust you are, and to dust you shall return.”

For the sin of striking the rock the second time, as we know, Moses and Aaron were both sentenced to die in the wilderness rather than lead their people into the Promised Land. To the modern reader, the whole thing seems more than a bit unfair. But hopefully the Lord’s reasons are becoming a bit more clear to us now. As I mentioned in an earlier essay, we can see those reasons more clearly still if we consider what happens next:

What if Moses hadn’t died? What if he had gone on to lead the people across the Jordan? Could a man in his role, now apparently prone to striking things to which God had commanded him to speak, really continue to lead them into the Promised Land? I think not. After all, the entrance to Canaan was Jericho, and the walls of Jericho turned out to be another “rock” which was not meant to be struck but “spoken to.” Joshua was the man for that hour, as was Moses for his own.

Out Of The Mouths Of Babes

Why, though entreated by the devil and some of our very own prayers, does our Lord ultimately refuse to play the power game? Jesus himself gives the answer: Though his kingdom has entered this world, it is not of this world. The subtle physics of heaven is not power but authority—patient lordship over natural and spiritual realities via relationships of trust and trustworthiness.

Like treasure hidden in a field, like a mustard seed becoming a tree, like a little bit of yeast working through the whole batch of dough, so is his dominion. In a world transfixed by the power of nuclear bombs and artificial intelligence, the slow and subtle outworking of seeds and yeast would seem a feeble force indeed. Nevertheless, in the truest story ever told, the fury of the storm is not overpowered by a similar act of fury, but calmed by the breath of a word. “Out of the mouths of babies and infants, you have established strength.”

Here is my microbe of faith: I believe that Jesus Christ spoke to the storm, and that the storm obeyed him, not as an impersonal force ‘obeys’ a sorcerer or a scientist, but as a child obeys her loving father, because she loves him in return. I believe that Jesus spoke as a man, as Adam would have and could have spoken. Call it “supernatural” if you like (you would not be wrong). But it is no more supernatural than saying, “Pass the salt,” rather than picking it up yourself. In a proper relationship of trust, call-and-response is as ordinary as cause-and-effect. Finally, I believe that because he did this, we can too. In fact, I believe we must. We must learn how to speak to storms and mountains and broken bodies and confused minds. We were made for nothing less, and, as I hope to prove in future posts, our salvation involves nothing less than the restoration of this office. For faith and authority—faith and dominion—are not two separate things but one.

I don’t say it will “work.” Not right away. Not easily. I can’t say it’s working for me. The storms and mountains have little reason to obey me if my own body still won’t. Perhaps I haven’t given them reason enough to trust me yet. But they are slowly getting to know my voice. And I pray that each day it would sound more and more like His.

Thanks to Richard Jordan for this language.

See Lewis’s That Hideous Strength for a terrifying and prophetic example of this in fiction.

'The physics of Heaven is call and response.' <-- bars! Thank you Ross

Outstanding work, Ross: I will be suggesting this piece to others. Connecting the question of "dominion over nature" with Moses and the mustard seed is very illuminating. Thank you very much for your work!