Love Is Not A Laser Beam

Love Is A Circulatory System

Hello friends,

My writing time is short in the summer months because of surf camp, but this little topic kept coming to mind after my June essay on forgiveness, so I had to get it out. It’s a bit rougher than usual, but it has lots of good poetry, so I’m hoping that makes up for it. Much love to all.1

The Gospel According To Phantastes

Love, in real life, is never quite what we think. It is much, much better and also seemingly far worse. And yet there is nothing better than love. There is, in fact, no good at all but love, even when we only taste its bitterness.

I re-read George MacDonald’s Phantastes recently and discovered once again that his writing sings this truth in almost every line. But there’s one particular scene and theme from the book which has haunted me more than any other. It has to do with MacDonald’s very counterintuitive perspective on love and the suffering of love.

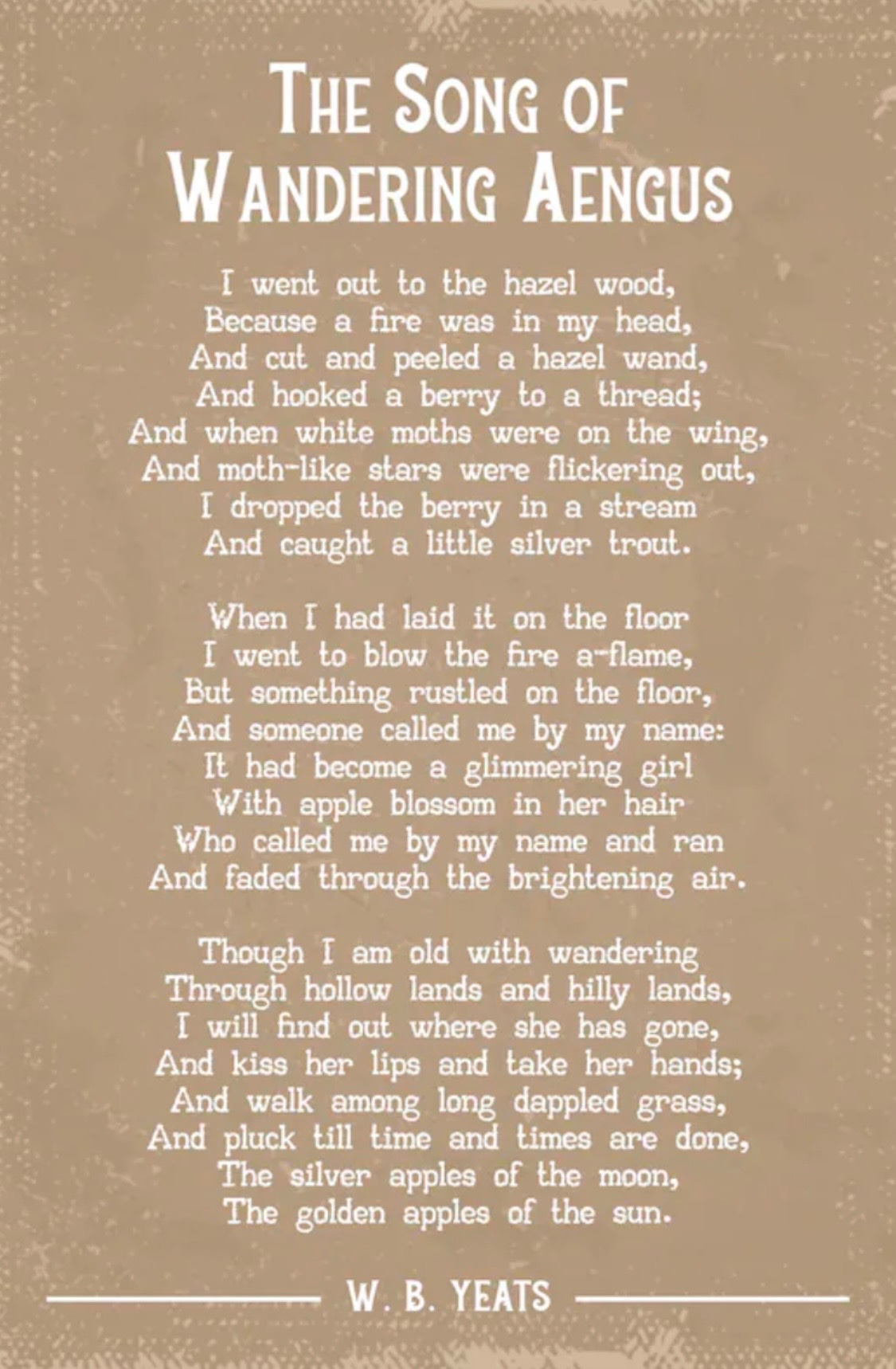

Earlier in the tale, the protagonist Anodos discovers the statue of a beautiful maiden, which he manages to awaken by singing to her. Once awakened, the maiden runs from him, and Anodos spends a good portion of the rest of the story chasing after her, to no avail. The whole episode calls to mind this enchanting bit from Yeats:

Later in the story, a kind fairy woman allows Anodos to take refuge in her home. That night, she shows him, in a vision, the woman he has been chasing. In the vision, the woman chooses to be with another man, a knight, who, by all accounts, is a better man than Anodos. He knows now for certain that he cannot be with her. He is second best, the “moon” to his “sun.” The maiden must be with the knight, not with him. He had perhaps been worthy enough to awaken her, yet not worthy enough to have and to hold her.

When the vision is finished, he falls into the motherly embrace of the fairy woman, who sings a song over him as he mourns. The song begins by lamenting with Anodos (whose name means “pathless”), but goes on to offer a surprising remedy for the heartbreak of unrequited love.

O light of dead and of dying days! O Love! in thy glory go, In a rosy mist and a moony maze, O'er the pathless peaks of snow. But what is left for the cold gray soul, That moans like a wounded dove? One wine is left in the broken bowl! — 'Tis — To love, and love, and love. Better to sit at the waters' birth, Than a sea of waves to win; To live in the love that floweth forth, Than the love that cometh in. Be thy heart a well of love, my child, Flowing, and free, and sure; For a cistern of love, though undefiled, Keeps not the spirit pure.

What is the remedy for the love-shattered soul? To love and love and love, says the woman, in what must surely be the most offensive answer to modern ears. The same love which caused your heart to break is yet the only wine left in the broken bowl. There is no other sustenance. If you had not loved, perhaps you would not have suffered thus. But the cure for the pain is only to go further into its cause. To love and love and love.

Perhaps this was the episode which led C. S. Lewis—after all, this was the book that “baptized his imagination”—to pen one of his most memorable meditations on the subject:

There is no safe investment. To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything, and your heart will certainly be wrung and possibly broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact, you must give your heart to no one, not even to an animal. […] The only place outside of heaven where you can be perfectly safe from all the dangers of love is hell.

But back to the fairy’s song.

What precisely is this love which promises renewal to the broken hearted and a path to the pathless? It is, she says, the love that floweth forth rather than the love that cometh in. Like manna in the desert, true love can be enjoyed only by being given and taken and shared, never by being stored up for tomorrow. “For a cistern of love, though undefiled, keeps not the spirit pure.” Oh my.

At the heart of the fairy’s “good news” is a truth rarely swallowed: that love is most truly itself not in the fact of being loved, but in the act of loving.

A more counter-cultural take on love you will not easily find.

Of course it stands in tension with our whole secular “self-care” moment. But it also seems to call into question many of our modern Christian articulations of “the gospel,” which tend to focus, almost entirely, on “the love that cometh in.”

The gospel, we insist, is that we are loved by God. This, apparently, is the good news our hearts have longed for. Yet why doesn’t it bring the lasting comfort which its words imply? Why doesn’t it stick? Why must we keep coming back, keep reassuring ourselves with the same bit of information over and over again? Of course, I am far from denying that we are infinitely loved by the One who made us. There is perhaps no greater truth in the universe than this. I simply deny that we can receive this truth—this love—as such. We are not cisterns, but fountains. Our hearts were not built to store up. We were built to overflow.

As I argued in my last piece, for Jesus and the apostles, the love of God does not function like a laser beam but a circulatory system. It does not flow one way only, and it certainly does not stand still once it arrives at its destination. Just as with our physical hearts, our spiritual hearts can only receive as they give and can only give as they receive. Input and output are inextricably linked. A cistern of love, though undefiled, keeps not the spirit pure.

“We love, because he first loved us,” (1 John 4:19) is not merely an explanation of where our love comes from. Of course it comes from God. But the apostle John is making a much bolder claim about what salvation is. He is saying we love because he first loved us. The sinner saved by grace is not merely the one who escapes condemnation and death; he or she is the one who enters irreversibly into the cosmic circulatory system of God’s infinite love, becoming not only blessed by God but actually like God, giving as he receives and receiving as he gives. The life he receives in Christ is quite literally the love of God, flowing out and flowing in and flowing out again, forever and ever. Salvation entails nothing less than the seemingly impossible transformation of the human heart, to love as he loves.

This is what has always captivated me about MacDonald’s writing. In each of his stories, reality takes on a quality—Lewis called it “holiness”—that is just too much for the protagonist, too good and true and real and palpable for any mortal soul to bear. And yet, the character must bear it, must obey it, must do precisely what he cannot do in the moment when it is most clear that he cannot do it. He must participate in the holy. He must be eclipsed by it, and yet somehow must become finally alive and real within it. All the forgiveness and redemption we know we need can only become ours by entering into and participating in that which most proves our unworthiness to receive it. To paraphrase Macdonald’s own words from elsewhere, the fire which burns us becomes our life. And that fire is his love. Nothing is as terrifyingly demanding as the love of God.

As Lewis explains (in an essay I can’t seem to track down at the moment), Dante’s famous concluding line about “the Love that moves the Sun and the other stars” is not exactly referring to the Love that comes from God, but rather to the Love of the heavenly bodies for God, which drives and regulates the Universe. Yes, they love because he first loved them. The planets wouldn’t exist without him. But in those heavenly bodies, Dante finally beholds that Love, which first made the world, now being properly returned to its Source in praise, giving shape to the eternal dance of all creation. And he is overwhelmed:

Here powers failed my high imagination: But by now my desire and will were turned, Like a balanced wheel rotated evenly, By the love that moves the Sun and the other stars

To put it almost too straightforwardly, the problem to which Jesus Christ is the ultimate solution is not merely, “How can God find a way to love us, despite our sin?” but rather, “How can God find a way for us to love him, despite our sin?”

What Christ accomplishes in us is nothing less than the transformation of our wills, of our wants, of our loves. We become worthy not merely because he calls us worthy, but because he makes us worthy by calling us and patiently forming us into lovers of the highest goods, into lovers of Him. Again, it is his love that does all this. But it is ours that must be changed. Otherwise there are no saints. Otherwise there is no salvation. A cistern of love, though undefiled, keeps not the spirit pure.

Notice that Jesus uses a similar image when speaking to the woman at the well in John 4:

Everyone who drinks this water will be thirsty again, but whoever drinks the water I give them will never thirst. Indeed, the water I give them will become in them a spring of water welling up to eternal life.

Love, like manna in the desert, cannot merely be stored up. It must continually flow between us and overflow in us, lest it spoil in the heart of the receiver.

The Light Princess & How Salvation Actually Works

All this brings to mind another one of my favorite George MacDonald stories, The Light Princess. In an opening scene reminiscent of Sleeping Beauty, a wicked witch, sister to the king, has been uninvited to her newborn niece’s baptism. But, being a wicked witch, she attends the ceremony anyway and pronounces a curse over the child in front of everyone. In MacDonald’s version, the princess’s curse is that of “lightness” or loss of gravity, an inability to feel or embody the weight of things. The curse manifests itself both physically (they have to tie her down so she won’t float away) and emotionally (she’s always happy and never cries). An odd curse to be sure! And at first, it doesn’t seem so bad. But happiness without the possibility of sorrow, almost like sunny weather, day after day, without the chance of rain, is not as pleasant as it might appear. By the time the princess is full grown, sure enough, the land begins to share in the princess’s cursed pattern. Just as the princess cannot produce tears, the land fails to produce rain. Drought and famine begin to threaten the kingdom.

Meanwhile a noble prince has arrived from a far off land. Each night the princess goes for secret swims in the lake beside the palace. She has discovered that the water is the only place where she has some sense of gravity. The prince meets her there and swims with her night after night. Soon he falls in love with her. But whenever he sings to her of his love, she only laughs. She cannot seem to take him seriously.

Nevertheless, the witch becomes very concerned about the possible progress which the lake and the prince seem to represent. So she cuts a hole in the bottom of the lake, and the water begins slowly to drain away. With no rain to replenish it, the people say the princess will not live an hour after the lake is gone.

Around this time, a strange prophecy is discovered, written on a plaque near the bottom of the lake:

Death alone from death can save. Love is death, and so is brave-- Love can fill the deepest grave. Love loves on beneath the wave.

The prince concludes from this that he must give his own life for the life of the princess, plugging the hole at the bottom of the lake with his own body. “She will die if I don’t do it. And life would be nothing without her. So I shall lose nothing by doing it.”

The reader is then led to believe that the prince’s sacrifice alone—his life for hers—will be enough to save the princess and possibly the kingdom. A clean exchange: the prince’s life for the salvation of all. A familiar story, no?

But the prince knows better. The prophecy proclaims no mere magical transaction. True salvation doesn’t work that way. After all the nights spent with the princess in the lake, the prince has come to understand that her curse is complex: it is not only on her but in her. It is hers now, not just the witch’s. And it manifests itself most deeply as an inability to love. He knows that, if his sacrifice is going to break the spell, it cannot merely bring her to life; it must bring her to love. And so, just before he dies, the prince sings to her:

As a world that has no well, Darting bright in forest dell; As a world without the gleam Of the downward-going stream; As a world where never rain Glittered on the sunny plain; Such, my heart, thy world would be, if no love did flow in thee. Lady, keep thy world's delight; Keep the waters in thy sight. Love hath made me strong to go, For thy sake, to realms below. Let, I pray, one thought of me Spring a little well in thee; Lest thy loveless soul be found Like a dry and thirsty ground

When the prince finishes his song, the princess only laughs. In usual fashion, she is happy to have the prince give his life so that she can go on swimming in the lake. But when the prince goes down to his death, the princess finally sees the meaning of it all. She tries to save the prince, but by the time she pries his body from the depths, there is no life left in him.

And so, finally, she cries.

As the tears flow down her face, her spell is broken, just as the prince hoped it would be: “Let, I pray, one thought of me / Spring a little well in thee.”2 Rain falls on the land again, a rainbow stretches across the sky, and a waterfall fills the lake brimfull. The witch is defeated and the prince is revived.

“Death alone from death can save,” we find, did not apply merely to the prince’s sacrifice, but to the princess’s response. Both had to die, in a way, so that the princess could be made well, and so that the two could live happily ever after. The prophecy had to be fulfilled not only for her, but in her. And the end result is love.

In Conclusion: Love Is Better Than Life

Let me try now to say in a few simple words what is much more powerfully portrayed in poetry and fairy tales. Love is our life. Or, as King David famously proclaimed, “Your love is better than life” (Psalm 63:3). The “eternal life” we gain in Christ is not actually life as we normally see it at all: not eternal existence, but eternal love. Our Savior came to give us not perfect survival, but perfect union with him.

I am especially grateful for the works of George MacDonald, which have opened my eyes to this reality again and again.3

Thank you Jennifer Downer for the encouragement to write about Phantastes!

“Tears are the only cure for weeping.” - the old fairy woman to Anodos, Phantastes

I just finished re-reading what is perhaps MacDonald’s deepest (and most difficult) novel, Lilith, with some of my surf camp staffers, and boy is my mind blown right now. Don’t even know what I would write about it at this point, but perhaps one day I will try to express for you some small part of what that story has given me.

wonderful wonderful writing getting at the heart of MacDonald's tireless message. Loving God is awful, painful, terribly consuming. But we are called to be fountains of living water, constantly giving. How miraculous that I can in any way pour out my meagre love on God, and He accepts it and embraces me in my attempts at loving. This is so relational, so anti-passive, so anti-self-focused. Love it!

Beautiful articulation of the gospel. Thank you for this reminder to seek first the law of the kingdom, for he can add all the other things. It is so easy to get burdened by the brokenness, but as I love him, and let that circulatory system of love flow through me, his love will bring the renewal. He makes all things beautiful in his time.