If You Do Not Forgive

Meditations On The Other "Unforgivable Sin"

Some passages in Scripture are hard to interpret, because their meaning is subtle. The true significance may be buried beneath the surface, waiting to be unearthed. Others are hard for the opposite reason, precisely because they are so plainly stated. They are hard to see, not like a needle in a haystack, but like the sun.

“Forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us,” is one such blinding light.

It comes in the middle of the most famous prayer in the middle of the most famous sermon of all time. We all know it. Many of us have prayed it thousands of times. Yet, its plain meaning is rarely swallowed. And lest we were tempted to settle for some subtler and more palatable interpretation, Christ himself seems to block off the exits with his very next statement:

For if you forgive others their trespasses, your heavenly Father will also forgive you, but if you do not forgive others their trespasses, neither will your Father forgive your trespasses. (Matt. 6:14-15)

What could this mean other than what it straightforwardly states: If you do not forgive, you will not be forgiven? On this passage, I want to suggest three (possibly contentious) points:

We don’t tend to take Jesus at his word here.

He absolutely means what he says, and we ignore it at our peril.

Nevertheless, there is a secret mercy hidden in our Lord’s threat of unforgiveness.

WARNING: Point #2 is kind of a wild ride, as I end up wrestling with the bigger problem of how we do theology in general. But stick with me; it’ll pay off.

1. We Don’t Really Believe It (Forgiveness as Impossibility)

Imagine your minister delivering the following message on Sunday morning: “If you do not forgive, God will not forgive you.” How would our modern congregations—evangelical, progressive, or otherwise—receive that message? I’m fairly confident it would cause some confusion, possibly even outrage.

“Heresy! Works-righteousness! God’s forgiveness contingent on our forgiveness? Never!” Yet this is the teaching of our Lord, not only in the Lord’s Prayer and the Sermon on the Mount, but also elsewhere, as in the Parable of the Unforgiving Debtor (Matt. 18:21-35).

The Protestant—and, going back even further, perhaps, Augustinian—tradition has taken a clear stance here, which is worth summarizing at some length:

“Despite what Christ seems to say, our forgiveness is in no way conditioned on our performance. If it were, there would be no meaningful forgiveness of sins at all, since we could never hold to our side of the bargain. Sure, Christ spoke these words just as he also commanded us to be perfect as our heavenly Father is perfect. But he was merely restating the law of Moses, against which we have all been weighed and found wanting. His threat of unforgiveness is not so much false as out-of-date. The law does not have the final say. Grace does. No one could perfectly forgive their neighbor; no one, that is, except One. And thanks be to Jesus, who has done the forgiving on our behalf, who declared on the cross, ‘Father forgive them, for they know not what they do.’ Since he has done it, we do not have to. We are justified, not by our own obedience, but by his work on our behalf. Thanks to him, the threat of divine unforgiveness has come untrue. If anyone continues to speak the same threat over us now, it is not Christ but the devil.”

I will not argue with this theory at present, some of which I believe to be true and some false, or at least confused. But this should suffice as evidence for my first point: we do not believe it, nor can we conceive of Jesus’s warning, in its plainest sense, as merciful or good for us.

2. He Means It (Forgiveness as Analogy)

I want to be careful here. There is some risk in insisting upon a truth like this, for my own sake as well as for others. For my own sake, I don't want to invite Christ’s condemnation of the Pharisees upon myself. I don’t want to heap burdens on the backs of others which even I cannot carry. For others, I don’t wish to scandalize, to make you choke on a truth you weren’t yet prepared to swallow. These are real dangers. And yet, I fear an even greater danger on the other side, in evading or downplaying a truth that must be swallowed.

The history of Christian theology is chock-full of biblical interpretations that do not so much explain the words of Christ as explain them away. The temptation is understandable. An awful mystery has been placed before us: nothing less than the promise of unforgiveness for those who do not forgive (which, by the way, is seemingly all of us). But in our rush to explain it and resolve it, we forget that God in Scripture has called us again and again to wait, to trust, and to ruminate. To obey, even when we do not yet understand. To obey in order to understand.

So let’s begin with another thought experiment. Imagine that Christ’s words in the above passage are really, actually true. If you forgive others their trespasses, your heavenly Father will forgive you; if you do not, he, quite literally, will not. Let's assume that this is as true as the law of gravity, yet without throwing out all the other truths which you already accept regarding his grace and mercy and sacrifice, which might seem to contradict the present notion. Simply swallow it all. How, then, will the puzzle pieces fit together?

Perhaps we cannot know, at least not immediately. And what if the knowledge we lack is found precisely in the act of obedience, which we have been told so often we cannot accomplish? After all, it is Christ’s own words which suggest continually that our dealings with others are directly related to our dealings with him. Perhaps as we begin to do what he says, we will find out more and more how true it all is, how the pieces fit together.

But this, you say, does not compute. He has trapped us in a contradiction: If we follow and obey him, if we do as he says, then we can receive his forgiveness. Yet, we cannot follow and obey him, which is why we need his forgiveness in the first place.

But the contradiction is not as stark as we suppose. In fact, we are the ones making it so stark, not him. And we have done so in a very peculiar way.

First, we have unthinkingly assumed an “all-or-nothing” framework when it comes to God, a framework I call uttermost theology.

In uttermost theology, we assume we can only ever understand God’s commands and promises in an all-or-nothing sort of way. Our theological categories of sin and forgiveness become so “high” and infinite in scope that we lack any earthly analogy for them. Although Jesus taught us to call God “Father,” we entertain no parallels between our Heavenly Father and our earthly fathers. Whereas an earthly father can be obeyed or offended in some specific way, be it small or great, our Heavenly Father, according to the uttermost theologians, can only be obeyed or offended infinitely. With him, there are no small, specific acts of obedience or disobedience, and likewise no small, specific acts of forgiveness. If we have failed once, we have utterly failed and require nothing but utter absolution.

But this “uttermost” logic is causing us to miss Jesus in some very important ways.

To be clear, there is a sense in which it is all quite true. God is infinite and infinitely beyond all we can comprehend. Yet, if that were all we knew of him, then we could know nothing at all. But that is not all. Instead he has “come down” again and again from the heights of heaven, revealing himself in and through the most mundane specificities of the earth. Every molecule speaks of him. And though no word or image or analogy does so with perfect accuracy, he insists on making himself known by lowly means: not only through angels and prophets, covenants and commandments, but through the actions of a prostitute and the mouth of a donkey. Without diminishing the transcendent glory of the Godhead, he has nevertheless condescended to us through small signs and great ones, and ultimately through his Son, so that by means of incremental revelation we might gradually come to know him. This is the story of Scripture.

Yet this paradox of transcendence and immanence is hard to digest. So rather than live in the tension, we tend toward one extreme or the other. And in “uttermost theology,” we tend toward extreme transcendence: “The commandments of Christ are so far above us that we could never even dream of obeying them.” But when we use this logic, we burn the bridge he built for us. Our seemingly “high” treatment of God’s commands and promises leads us, almost accidentally, to reject those same commands and promises in our daily lives. The commandments we claim to hold so “high,” we ironically never even try to keep, because we have deemed it impossible to do so from the start. We do not give body or action or application to his words, and thus we never even begin to know what they truly mean. And when we lose their embodied application on earth, we also lose the heavenly blessing that body was meant to hold. In other words (to give away the end in the beginning), we lose our capacity to receive Him.

Don’t get me wrong. The commandments of our Lord are certainly “high” commands. They are reflections of the infinite, glimpses into the kingdom of heaven. Nevertheless, our experience of them must begin on the ground. “Thy kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven,” he says. In fact, every element of the Lord’s Prayer is like this. The prayer descends from the Father “who art in heaven” into common requests about our daily lives. It’s about daily temptations and trespasses no less than daily bread. In a few lines, we descend from the hallowed throne of heaven to the minute particularities of earth—and even further, into hell itself (“deliver us from evil”)—in order, ultimately, to offer everything up to God again.

To take another example, even the greatest commandment, according to Christ, is not to “love everyone infinitely,” but to “love your neighbor as yourself.” Why? Because things must first be specific in order to become general. They must begin small and close, like a seed you can hold in your hand, which when planted, becomes a tree which can hold you in its branches. And you don’t need to know how it happens. It’s not your job to make the tree grow. But if you aren’t at least faithful enough to plant the seed and stay where you planted it, what do you know of seeds and trees?

Even before Christ, God could say this about his commands:

For this commandment that I command you today is not too hard for you, neither is it far off. It is not in heaven, that you should say, ‘Who will ascend to heaven for us and bring it to us, that we may hear it and do it?’ Neither is it beyond the sea, that you should say, ‘Who will go over the sea for us and bring it to us, that we may hear it and do it?’ But the word is very near you. It is in your mouth and in your heart, so that you can do it. (Deut. 30:11-14)

Of course, Christ’s commandments are higher, in some sense, than those of Moses, yet they are also nearer. They point “further up and further in” to the kingdom of heaven, yet that same kingdom is now “at hand.” The Word has become flesh, so that his words may become flesh in us.

What I am saying is that the commandments were not merely given as an unattainable standard (though they may also be experienced as such). They are not merely a measure of justice, by which we fall short, but also—and perhaps even more so—a means of grace, by which we participate in him. As we do what he says, we come to know him. Each act of obedience becomes a kind of lived analogy. Without obedience, even imperfect obedience, we could not know him at all.

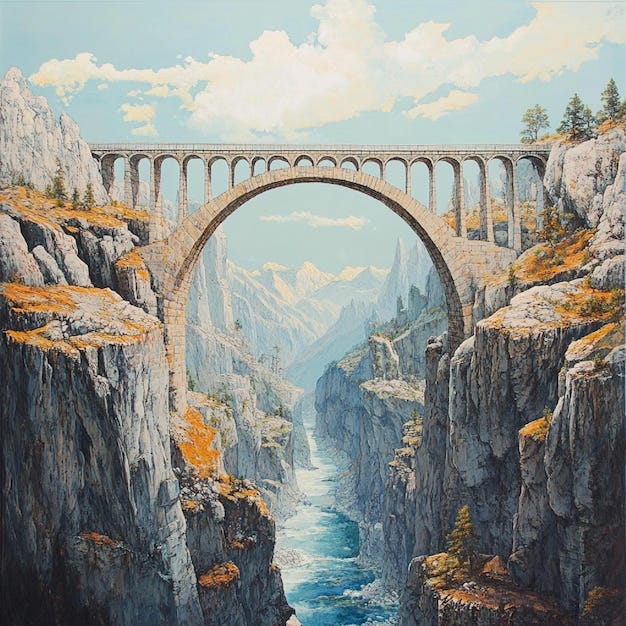

To return to the main example of forgiveness, we could not even conceive of the nature of the Father’s forgiveness except by struggling to forgive those who trespassed against us. Our daily acts of forgiveness—and, likewise, all acts of faith and obedience—become a kind of bridge by which we can finally experience the Father’s forgiveness. I do not mean that such acts make the Father’s forgiveness possible. It was always already possible in Him. Rather, it makes us into vessels who can receive and carry it.

This, however, does not fit into the “uttermost” framework.

“No bridge but Christ!” they say. And, to be clear, I don’t disagree. I’m simply stating the obvious: that a bridge is only useful to those who step out onto it. But the uttermost theologians object, since such a salvation entails taking steps at all. “Christ has spanned the expanse so that we don’t have to!” Sure, but we still need to get to the other side. “Christ takes us with him!” But how? It apparently just…happens. They have unconsciously traded the image of walking for that of teleportation, a natural and biblical analogy of faith for a magical and non-existent one.

And this is the problem. Ancient Christians envisioned a more patient union of heaven and earth. Jesus said the kingdom of God was like a mustard seed which becomes the largest tree in the garden—a seed which dies and grows roots and eventually sprouts branches, which reach imperceptibly slowly toward the heavens. A tree knows no other way but the long game. And they took this seriously. In their view, the God-man descended from heaven to earth in order to take and call earth up into heaven by means of daily, ordinary acts of trust, love, and faithfulness. Not that they imagined “earning” their way to heaven, as if such a foolish Tower-of-Babel project were possible. Rather, they assumed Jesus was calling them to participate in heaven, by his grace, here and now. “Follow me,” Jesus said. And they obeyed, or at least tried to.

By contrast, for us modern “uttermost theologians,” the whole journey between heaven and earth must be accomplished all at once or not at all. “It is finished,” replaces “Follow me,” rather than fulfilling it. The objective work of Christ replaces the subjective faith and faithfulness of the believer, rather than making it finally possible. The cross cancels discipleship instead of becoming its central symbol.

Without the tree-shaped bridge of participation, heaven and earth remain for us entirely separate entities, to be traversed only by means of divine teleportation. Salvation, once understood as mutual, self-giving relationship, becomes a kind of one-time transaction. The marriage of heaven and earth is replaced with a one-night stand. The whole cosmos is then bifurcated into “natural” (which means corrupted) or “supernatural” (which means deus ex machina), with nothing to bridge the gap in between. Our nature cannot be lifted up to God, and his super-nature cannot do anything but conquer and replace our corruption, which is to say, our whole selves.

But Jesus’s own ministry does not work this way. He does not come conquering and replacing. Rather, he comes speaking. He treats the things and creatures of this earth as still in some sense good, as still having at least enough agency and dignity to be spoken to by their creator. He tells the storm to be still, and it obeys. He tells the paralytic to pick up his mat and walk, and he obeys. He even tells his disciples that they may say to this mountain, “Move from here to there,” and it will move. And yet we are somehow to believe that he does not expect our obedience when he tells us to forgive those who have trespassed against us.

It is absurd.

I am not saying we can easily obey. On the contrary, we are sinners—as wild as the storm and as helpless as the paralytic. But if he says, “Walk,” we would be crazy not to try. And yet, as uttermost theologians, we do not try. Rather, we have transformed the palpable realities of obedience and sin and forgiveness and all the rest of it into technical theological terms of the uttermost heavens, which have no earthly specificity or application. “One sin,” we say, “is the same as a million.” Which is to say, it’s all an abstraction, to be resolved by another abstraction.

In such a world, what can forgiveness even mean? What does it feel like to forgive? What does it feel like to be forgiven? In the uttermost frame, we do not know. We have lost all analogy. Because we have not believed Jesus’s words about forgiveness, we have not done them. Because we have not done them, we have not understood them. And because we have not understood them, we have not even wanted to be forgiven. For wanting presupposes some knowledge of the thing wanted.

This is where we find ourselves as uttermost theologians of the 21st Century. We have avoided and disdained the specific teachings of Christ today, which might have been our bridge to knowing him, and have instead doubled down on an abstract and generalized blessing for tomorrow, which requires nothing other than the belief that we will receive it regardless of what we do or do not do, despite Christ’s clear words to the contrary.

We are like those who know we must make a very great and perilous journey, in which only one man has ever succeeded. That very man stands before us, pleading with us to follow him across the great abyss. If we do not, he says, we will surely die. Yet instead of fixing our eyes on him and putting one trembling foot in front of the other, we hang back, entertaining the rumors of some dreamlike technology which will get us to our destination without any effort on our part.

This, apparently, is our “good news:” not that the Son of God has bidden us to repent and to follow him as he leads the way to his Father’s house, where there are rooms prepared for us; but that having ignored and disdained his invitation, he will nevertheless take us where we would rather not go. “Christ will carry us!”

I think I understand why so many of us have come to believe this. As I have said, I believe some small part of it myself. But I would rather have him as my Lord today than as my divine technology tomorrow. I would rather at least try to do what he says, and when I fall short, cry out to him. At least then, when he hears, “Lord, Lord,” he will know my voice. And if he knows me, he will not leave me behind.

3. It Is Good (Forgiveness as Capacity)

Now that we have reclaimed analogy, and have seen at least in part how even small acts of real forgiveness become a bridge by which we can begin to conceive of and long for the infinite forgiveness of our souls, let’s go a step further. Our forgiveness of others offers far more than understanding and desire. It actually affords us the capacity to be forgiven, to receive a gift which we would otherwise have no room for.

See, the logic of the Uttermost God produces a world of what I call “laser beam doctrines.” In this world, the love of God and the blessings of Christ flow in a strict one-way current from God to us. He gives. We receive. That is the gospel. It is always about “being forgiven,” never about forgiving. In laser beam economics, it is not “Forgive us as we forgive,” but “Forgive us because we do not and will not.” But open your New Testament and you find a very different economy playing out in the teachings of Jesus and the other apostles. In the kingdom of God, love is not so much a laser beam as a circulatory system. Just as with our physical hearts, our spiritual hearts can only receive as they give and can only give as they receive. Input and output are inextricably linked.

I realize what this sounds like. Believe me, I do. But in my defence, I’m not the one who speaks this way about forgiveness. Almost no one does in the church today. But Christ did.

And yet, how could it be true? What symmetry or synergy could sinners possibly bring to the forgiving work of Christ? Again, we do not know. All we know is that our brother Christ has brought us a message from the Father: We must partner with him and the Father in their work. We must somehow participate in the circulatory system of their mutual love, otherwise there can be no place for us in their house.

But why? Why must he threaten our unforgiveness with unforgiveness? How could that be good? What is it specifically about our unforgiveness that might keep us from receiving the Father’s forgiveness?

Aha. Receive. What if the problem with forgiveness is not exactly that he will not give it, but that we cannot receive it? He cannot speak a word that will return to him void. Which brings us deeper into the notion of what forgiveness—and salvation—actually mean.

If forgiveness were a mere technical transaction, if “receiving” only meant that the stamp of absolution had been magically placed upon you, with or without your will, that would be simple enough. But if the forgiveness of God is primarily about restoring a relationship, well then, that is a more complicated matter. Then the receiver becomes a central part of the problem. God cannot merely give the gift he would like to give; he must find a way for us to be able to receive it (and therefore to receive him, which is the end of salvation). And, of course, that is exactly what he does.

Throughout Scripture, God’s primary mode of operation is relational. He relates to his people through covenants and commandments, through calls to faith and faithfulness. He works with and through imperfect men and women, not merely despite them. They must—the whole story seems to depend on it—actually heed his warnings, answer his calls, believe his promises, offer their only son on the altar, and speak to the rock instead of striking it. And even when they fail, striking the rock instead of speaking to it, God is faithful to carry out his purposes in their midst, yet again, not merely despite them, but through them. The whole thing is a two-sided relationship, because, of course, you cannot marry someone who doesn’t want to marry you.

This is how God saves the world. The love of God will not be eclipsed by our darkness, and yet somehow neither is the beloved eclipsed in his light. Because of his love, we shall neither die in the darkness (death by alienation), nor die of his light (death by holiness). We shall truly marry him. But we must be a pure bride. We must be sanctified if we want to be saved. Put another way, we must want to be saved if we want to be saved.

And he is patient. He plants the seed, tills the soil of our hearts, and waits for our love to grow. Just as trees are not merely zapped into existence, neither is the kingdom of God zapped into its fullness. When Jesus enters the scene at the beginning of the Gospels, he does not come giving out prizes: “Forgiveness for all!” Instead the message is this: “The kingdom of God is at hand. Repent and believe the good news.” And what is this kingdom like? “Like a mustard seed, which becomes the largest tree in the garden.” The marriage of heaven and earth cannot be merely announced in order to be enacted. First, both parties must take their vows.

This is the main problem with the Jesus-did-it-so-we-don’t-have-to gospel. Of course we have to. If we do not, we shall never be married to him, and we shall never be saved. Yes, grace speaks first. But it speaks in order to hear its beloved respond. He brings great gifts, but the gifts are not a one-way, laser-beam transaction. They are an invitation into a mutual relationship. “Repent, believe, follow,” “ask, seek, knock,” “eat my flesh and drink my blood,” “forgive or you will not be forgiven”...this is the language of urgent invitation into participation in him. It is a wedding proposal, a call to enter through his wardrobe, to taste and see, perhaps even to settle down and live in the world where he is king.

“If you do not forgive, you will not be forgiven” is not primarily a reflection of the Father’s justice, but of his mercy. It is the loving father who warns his son, “Do not take that path. It will not lead you out of the woods, but only further in.” But for the son who doesn’t trust his father and insists on going his own way, the warning can only be a judgement.

Near the end of The Last Battle, Aslan stands at the door of his eternal kingdom and opens his mouth to speak. Those who trust the Great Lion hear his loving voice welcoming them in. Those who do not trust him, at the same moment, hear only a snarl. The difference is in them, not in him.

If we will not enter his world, how can we partake of his gifts? And why would we enter if we are already content within our own kingdoms here and now? How can we receive his gifts if our hands are already full? It is hard for the rich to enter the kingdom of heaven, because entering means emptying. So much of Christ’s teaching revolves around these two themes, which are really the same theme: emptying and entering. The gift is indeed free, but we still cannot afford it. Why? Because, as he says repeatedly in the Sermon on the Mount, we have already received our reward. In this light, the very first line of the sermon can be seen as the key to all that follows:

Blessed are the poor in spirit,

For theirs is the kingdom of heaven

Why must we forgive? Because forgiveness makes us poor, so that we can finally be rich. Because forgiveness is the opening of our hands to God, precisely as we empty them of all our grievances. To forgive is to join his circulatory system of love, which is the heartbeat of the cosmos. Whatever we withhold for ourselves, that is what we cannot receive from God. The earthly treasures we store up here and now, including even our just judgements against those who have wronged us, take the space which heavenly treasures could have otherwise filled. We can hold on or we can let go. We can have one “reward” or we can have the other. But the one thing we cannot do is have both. We cannot serve two masters.

This has been one of the most difficult pieces I have ever written. I do not expect that it will have convinced most of my readers. Nor do I wish to scandalize you beyond what your conscience can take. For generations, we have preached that the free gift of God comes with “no strings attached,” an idea which cannot—and perhaps should not—be upended in one fell swoop. But as I have argued in previous essays, true grace is a gift with strings attached, and those strings mercifully bind us to Him. “Forgive us as we forgive” is one such string. Such a gift affords us the salvation of restored relationship. It affords us the ability, finally, to love Him and be faithful to Him as he has been to us. And this is precisely what it means to be saved.

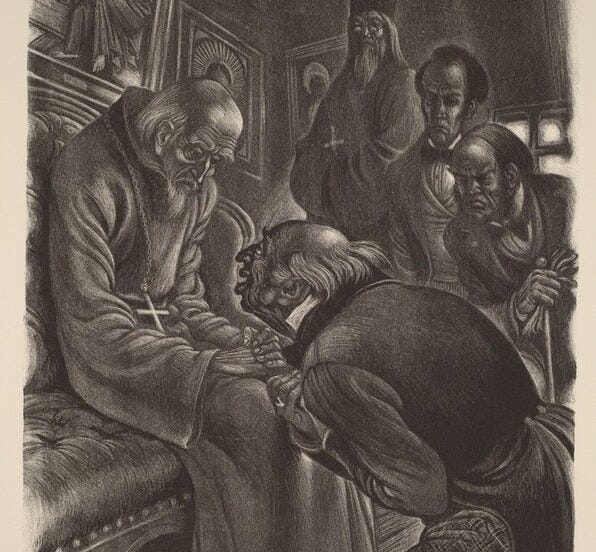

“What is hell?” asks Father Zosima in The Brothers Karamazov. “I maintain that it is the suffering of being unable to love.” So Lord, open our hearts to love others as you have first loved us. And forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.

P.S. If you were expecting this essay to delve more practically into the complexities of forgiving others, stay tuned. This is the first in a series on forgiveness. More to come in due time. And I promise it will get more practical from here.

P.P.S. Big thanks to Griffin Gooch, Colby Edwards, Nick Cummings, John Gayle, and Matt Fittro for reading and offering your thoughts when this essay was in its painfully unfinished stage. It’s probably still unfinished, but it’s much better than it was!

This was very very good to read Ross. It gets to the heart of a lot of what I find lacking across many denominations I have attended or visited. There can be no expectation of discipleship if we are utterly incapable of doing anything except sinning and confessing in a vicious cycle, waiting for Jesus to come back and justify us because we called upon His name.

We know in our hearts it's true that we are called to keep attempting to live as Jesus commanded, to reach towards completion/perfection (despite our failings), to allow each time we succeed in pleasing God's heart and each time we fail be a way for our capacity to forgive and be forgiven (or love and be loved) be expanded or deepened. There is a scurrilous cowardice in the way churches teach (implicitly and explicitly) that we are all sinners and there's no hope in trying to follow Jesus perfectly/purely.

Thank you for taking the time and effort to write and share this clarifying essay.

Great stuff.

The modern man only has faith in his own internal experience. Anything outside of what he sees or feels is viewed as illusory. The modern man doesn't really believe in friendship as an external reality, but only as an internal experience. The same is true for love, glory, honor, beauty, goodness etc. Even in the evangelical world, this has become the norm. Which is why the fruit of the spirit - "love, joy, peace, longsuffering" etc. - are so often talked about as internal experiences rather than realities that exist between us. Forgiveness requires faith in a reality outside of my own internal experience. Thus why the modern man manages relationships in all sorts of complex ways, while never truly forgiving.