Wives Submit?

On Gender, Trust, & Trustworthiness

So I am lecturing the VB Fellows this week on “Gender and the Christian Life,” and I thought I’d give you a snapshot of how I teach on the subject. Needless to say, the topic of gender tends to raise everyone’s blood pressure a bit (or more than a bit). I promise to do my best not to raise it further with what follows.

Talking About Gender

In my experience, there are three main ways to talk about gender in contemporary discourse. The first is to talk about gender inequality. Most of such talk, of course, points toward the inequities and injustices experienced by women, though there is also a small but increasing faction of young men online who, in reaction to the modern backlash against masculinity, claim that they are the true victims. Either way, in my opinion, this is the most natural way to talk about gender today. People do it all the time.

The second is to talk about whether or not gender exists. A debate, which began only a few decades ago in obscure academic circles has now become commonplace on social media, and from there, has spilled over to dinner tables across the country. Whether the debate will hold onto its place in the limelight for decades to come is anyone’s guess. Some believe it has already peaked, especially since the denial of the gender binary not only rejects the core assumptions of every traditional culture but also the core assumptions of the L, the G, the B, and the T. But that is a topic for another day.

The third is to talk about gender itself: male and female. How are they different? What is the meaning and telos of masculinity? Femininity? Oddly enough, this has become, for many of us, the most unnatural of the three. Probably it is still common in other cultures—surely, in other times—but not here. In our culture, public discourse about gender itself is increasingly rare. In more and more contexts, we prefer to be gender-blind. And we have our reasons. If you don’t understand what I mean, you could imagine a correlate: race. It is natural to talk about racial inequality in our time. It is much less natural to talk about race itself, as we experience it, noting differences across racial lines, etc. And, I think, for good reason. The categories of race are slippery and can be defined and redefined by those who would use such definitions for selfish gain, a problem our country has experienced for most of its history. We are wise not to fall too easily into the trap of constantly cataloging racial differences.

But the categories of male and female—despite the radical arguments of some today—are generally fixed categories and are, as compared with race, much more fundamental. We live with and depend upon these categories for our daily existence, and yet we are increasingly blind to the qualities which shape and define them. Those, especially women, who still feel the negative effects of inappropriate and prejudicial treatment may argue that we have not yet become gender-blind enough. This is understandable. But there is also a cost on the other side. In the 21st Century, with our powerful microscopes and telescopes, we can definitely see things our ancestors could not. But we’ve also become blind to certain things which our ancestors could see quite clearly.

The Bible, for instance, sees gender quite clearly. Yet, that does not mean the differences between male and female, masculine and feminine, are entirely simple and straightforward. Personally, I follow C. S. Lewis in the belief that the created realities of “male and female” reflect something deeper, more complex, and more beautiful than we can adequately account for with our social conventions or biological dictums. In my view, the question, “What is a woman?” defies both the recent conservative insistence that the answer is “simple” as well as the progressive proclamation that it is “whatever you want it to be.” Of course, in a sense, the answer is simple. Any three year old can say with 99% accuracy, “That is a woman.” And yet he or she will spend the rest of his or her life trying to figure out what that simple statement means. What does it mean to be a woman? What does it mean to be a man? Likewise, any biologist—at least, I hope this is still true—can point to the general differences between male and female physiology. And yet, a woman is not merely a biological entity any more than a mother is merely someone who has given birth. What is a mother, exactly? And how is she different than a father? Like the three year old, we know, but also we do not know. And, in some ways, we are increasingly forgetting.

But how do we go about remembering? If we are going gender-blind, how do we learn to see again without risking a backlash of the worst prejudicial effects, especially on women? How do we, as Christians, talk about gender, when there is simultaneously too much to say and yet almost nothing to say that would not be better communicated simply by trying faithfully to live out our complex asymmetrical roles, to which almost no words can do justice?

Here, at least, is how I have tried to do it.

Trust & Trustworthiness

The word “faith” in biblical Greek carries the meaning of both faith and faithfulness, or perhaps more accurately, trust and trustworthiness. This is the currency of God’s economy. It is how he gets things done. In a world of inanimate objects, where even human beings are thought to be made of mere matter, power would be the currency or mode of being. We would act in the world by moving things with our strength, and we would become whatever that strength would allow us to become. Some modern people believe we live in exactly this kind of world, and I do not deny that it appears so at times. But the Bible says no. In the beginning, God did not create mere things but agents/choosers not unlike himself. The world we actually live in is a world of mixed agency, where love, not power, is our mode of being. Power is subservient to love. “You shall love the Lord your God with all your…strength.” What we love, for better or worse, defines what we do and who we become.

Now, trust and trustworthiness are something like the left and right hand of love; they are the way that love operates in the world. And the Bible can actually be seen as an X-shaped story of trust and trustworthiness,1 where trust begins at the bottom-left and moves upward from earth to heaven and trustworthiness begins at the top-left and moves downward from heaven to earth. The goal of love is found at the center of the X, the marriage of heaven and earth, the perfect union of trust and trustworthiness. In the Old Testament, the Lord is the one who continually proves himself trustworthy while continually pleading with his people to trust him, usually by way of obeying his commands. This is the precise pattern of the Lord’s introduction to the Ten Commandments:

“I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of Egypt, out of the land of slavery. You shall have no other gods before me.” (Exodus 20:2-3)

Trustworthiness, trust.

There are a couple of things worth noticing in this simple passage. First, notice that this is the language of relationship, of asymmetrical mutuality. If we were mere things, then God would have no desire or need to prove himself to us or to command us to do anything for him in return. He would simply move us, and there we would be. That would be asymmetrical but not mutual. But this isn’t the way it works. Something is required of us in order to make God’s design complete. It isn’t exactly the same as what is required of God, because he is God and we are not. But something is required nonetheless. And that thing is trust. Second, notice that trustworthiness is not the same as absolute certainty. God has not revealed himself to us as an absolutely undeniable fact. If he had, again, that would give us no real agentic response in the matter. Rather, he has through his deliverance of his people from Egypt “come down from heaven” just enough to show himself worthy of trust, and has asked his people to lift up their trust to him, which they may or may not do.

And here’s where it gets interesting. Because, if they choose not to trust him, they will actually see less and less of his trustworthiness. Indeed, it will appear to them over time as though he is not trustworthy at all. But if they do trust him, they will see his trustworthiness confirmed time and time again until it is almost a certain fact. In other words, God’s economy of love is optimized by mutuality. It works by a kind of double-sided feedback loop where trustworthiness engenders trust, of course, but also and much more surprisingly, where trust engenders trustworthiness. Not that God is objectively becoming more trustworthy, but rather that his people are finally able to experience him as such, since trust is the lens through which we see him rightly.

And make no mistake, trust is a lens. It will change the way you experience reality for better or worse. You can read a book or watch a movie or listen to a song through the lens of distrust and hate every word of it. Then, two years later, with some new-found trust for that author, producer, or songwriter, you can come back to it and realize it’s one of the greatest pieces of art you’ve ever experienced. Or vice versa. This has happened to me more times than I can count. Trust transforms reality. But that doesn’t mean that trust is always good. If you put your trust in something that is not trustworthy—which the Israelites discovered over and over again in their worship of false gods—it will not go well for you in the long run. Likewise, if something is trustworthy, but you do not trust it—if a certain doctor can really cure your cancer, but you will not go to him, because you do not trust him—then you die. The magic happens in that place where trust and trustworthiness are truly aligned.

Wait, I thought we were going to talk about gender? Yes, sorry, I was getting to that.

Wives Submit To Your Husbands?

The relationship I have just described between God and his people is, symbolically, a gendered relationship, where God is the would-be husband and we, his people, are his would-be bride. (Notice, in the Christian frame, we all play the role of the feminine in relation to God.) He wants to marry us, but we do not necessarily want to marry him. He shows himself continually trustworthy and bids us to trust him. We continually fail to do so. Therefore, he sends his Son to embody for us both sides of the X: He comes down from heaven representing all the trustworthiness of the Father, yet, at the same time, he offers himself up to God in full trust and submission on our behalf. He completes the asymmetric union between heaven and earth, while also making a way for us to share in that union by faith. In him, we trust as he trusted while also embodying his trustworthiness in the world. This is what the Bible is about.

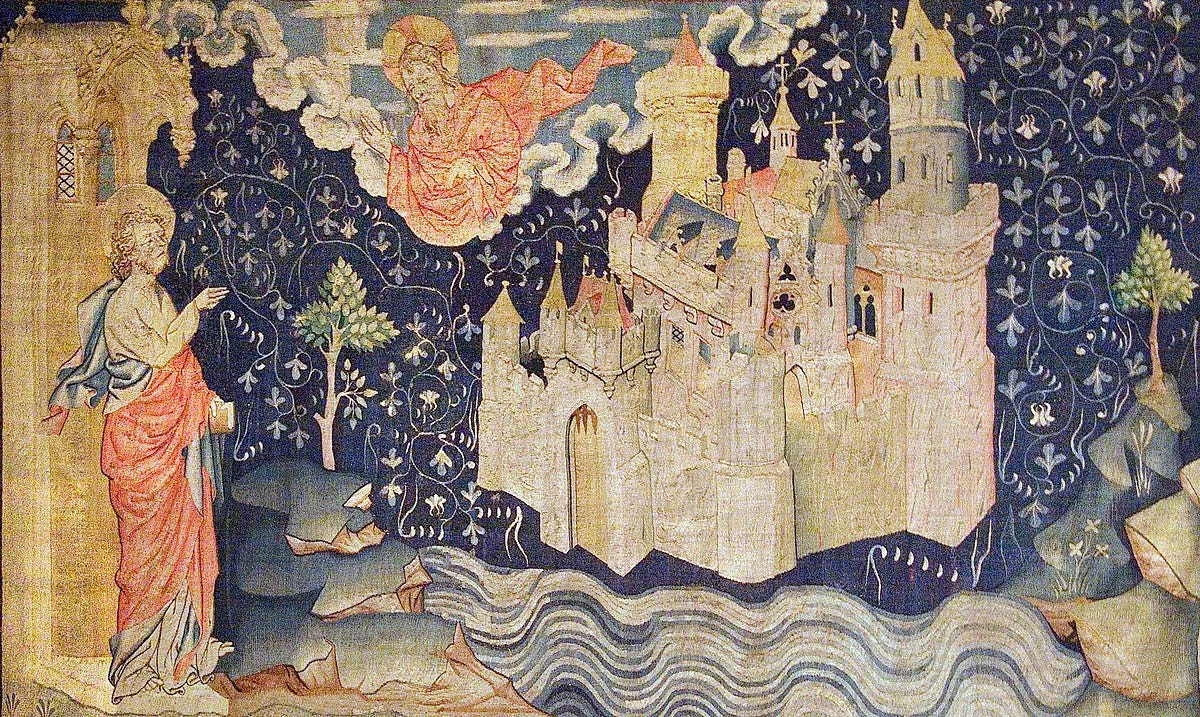

Anyway, human marriage between man and woman, from a Christian perspective, is really just a metaphor (albeit imperfect) for the ultimate union of God and his people. Human marriage is the shadow; the New Jerusalem is the reality. But through marriage—and through the asymmetric mutuality and complementarity of maleness and femaleness in the world—we get a glimpse of that ultimate union which perhaps cannot be learned any other way.

Now, I am probably starting to make some of your blood pressures rise already. You may have noticed that in the symbolic picture I’m hinting at, the masculine maps onto, well, God, and the feminine maps onto all the sinners who won’t trust him. This seems like just the kind of toxic characterization of women that we have been trying to avoid. I know, I know. Don’t worry. This will be sorted out. But first, let me get the rest of the offensive part out of the way by quoting everyone’s favorite wedding-day passage from Paul’s Letter to the Ephesians:

[Submit] to one another out of reverence for Christ.

Wives, submit yourselves to your own husbands as you do to the Lord. For the husband is the head of the wife as Christ is the head of the church, his body, of which he is the Savior. Now as the church submits to Christ, so also wives should submit to their husbands in everything. Husbands, love your wives, just as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her to make her holy, cleansing her by the washing with water through the word, and to present her to himself as a radiant church, without stain or wrinkle or any other blemish, but holy and blameless. In this same way, husbands ought to love their wives as their own bodies. He who loves his wife loves himself. After all, no one ever hated their own body, but they feed and care for their body, just as Christ does the church— for we are members of his body. “For this reason a man will leave his father and mother and be united to his wife, and the two will become one flesh.” This is a profound mystery—but I am talking about Christ and the church. However, each one of you also must love his wife as he loves himself, and the wife must respect her husband. (Ephesians 5:21-33)

Funny enough, I believe this passage from Ephesians 5 is the only recommended passage in the Book of Common Prayer marriage ceremony which I have never preached on at a wedding. The reason I haven’t, in this cultural moment, should be obvious enough. I don’t want to ruin anyone’s wedding day. And yet, I am convinced that this passage is widely misunderstood and would be far less offensive, though perhaps no less challenging, if it were understood rightly. Let me see if I can convince you.

Notice first that the passage begins with a generic call to all Christians, men and women, to submit: “Submit to one another out of reverence for Christ.” This should be obvious, but perhaps it’s still worth reminding ourselves: Submission is fundamental to the Christian faith. All Christians must submit, not only to Christ but to one another out of reverence for Christ. Christ himself made this constantly clear not only in his teachings but in his life.

“Whoever would be great among you must be your servant, and whoever would be first among you must be your slave, even as the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many.” (Matthew 20:26-28

The modern enlightened individual who treats “submission” in itself as something evil, cynical, or ridiculous is stepping farther away from the Christian understanding, not closer to it. For Christians, submission is the doorway into the kingdom. We cannot hope to escape it any more than we can hope to escape our own death (though hoping in the resurrection). Jesus saved the world by submitting to the Father, by “becoming obedient to the point of death,” says St. Paul, while calling us to do likewise. He who seeks to save his life will lose it, but he who loses his life, etc. This is not easy, especially in American culture, where the allergy to submission runs deep. We Americans were founded upon a revolution, an ousting not just of the king, but of kingship—sic semper tyrannis—and we would rather keep it that way. Why would you, especially if you’re a woman, who’s finally being given a break in this merciless, male-dominated world, ever willingly “submit” to anyone, especially to a man, even if he is your husband? Come to think of it, if you’re a man—a husband, say—and you’re actually starting to lose your historically dominant place in society, why would you give it up willingly? Why not rather fight to retain your dominance? The Christian answer to all this is simple. Power is not the power it seems to be; it is an inflationary currency which will buy you nothing in the end. Rather, love moves the world. Therefore, submit to one another, and you will share in the glory of your Savior who first gave himself up for you.

With that introduction, Paul goes on to paint a picture of what submission (and glory) might look like practically in the context of Christian marriage. “Wives,” he says, “submit yourselves to your husbands…” and “Husbands, love your wives…”

Now, the almost automatic way that modern audiences interpret this passage is to assume that Paul is commanding men and women—husbands and wives, in this case—simply to act in alignment with nature. Basically: “Women, you are naturally weak, so you must submit. Men, you are naturally strong, so you must lead.” No wonder we’re offended! But this is way out of sync not only with what the passage actually says, but also with the context of the letter, in which St. Paul, immediately before this chapter, envisioned the people of God growing up together into the spiritual body of Christ. In short, rather than saying, “simply act in alignment with nature,” Paul is actually calling the people of God to embrace a spiritual reality which transcends and redeems their nature.

Thus, when Paul says, “Wives, submit to your husbands,” he is not saying, “Women, you are naturally submissive, so do what you naturally do.” Nor is he telling husbands, “You are naturally trustworthy leaders, so go and lead.” In fact, I believe he is saying something closer to the opposite. To return to our framework of trust and trustworthiness, when Paul tells wives to submit as though to the Lord, his meaning is they should give trust. And when he tells husbands to love their wives as Christ loved the church, his meaning is that they should be trustworthy. And, in each case, he is actually calling men and women to transcend their natural state toward something higher. What do I mean?

Before I go on, let me just say that to speak in the framework of masculine and feminine is tricky, because it requires generalizing about a phenomenon to which an almost infinite number of individual exceptions might apply. Just because cats are generally furry and meow, doesn’t mean that every cat is furry or that every cat meows. What exactly constitutes masculine and feminine characteristics could be debated until the end of time, and even if consensus could be reached, every man would still have plenty of feminine tendencies and every woman plenty of masculine tendencies. Some women will seem more masculine than the average man and vice versa. All of this I accept. But generalizations, though imprecise, are nonetheless essential if we want to understand reality at all. Anyway…

The nature of the feminine, generally, is to be higher in trustworthiness, lower in trust. If you have the choice, in a moment of sheer emergency, as to which stranger should babysit your kids, a female is a good choice. That’s trustworthiness. And yet, because females have tended to be the more physically vulnerable sex and the sex that carries, births, and nurses children, they tend, wisely, to have a disposition which does not extend trust very freely. “What is this unknown red berry in the woods? I’m not going to try it, because it may kill me and my child.” Males, on the other hand, being slightly less physically vulnerable and entirely without the possibility of carrying or nursing offspring, are much more evolutionarily disposed to extend trust. “What is this unknown animal in the forest? Will it kill me or could I kill it first? Let’s find out.” Thus, men have always, on average, died younger than women, even though they tend to be stronger, faster, and less physically vulnerable.

The same can be seen with regard to emotional and psychological differences. According to 5-factor personality studies, men, on average, tend to be lower in negative emotion which allows them to extend emotional and relational trust more casually and often without the same downside as women. They also tend to be lower in agreeableness, probably for similar reasons, since there is less emotional risk in breaking the relationship. It stands to reason, then, that men would be less trustworthy than women, on average. It also stands to reason that, if you were conscripting an army, men would be the ideal candidates, since they will more easily extend trust (that is, submit!) to superior officers whom they have never met and who, no doubt, plan to lead them into grave danger. Never mind the fact that they may be less trustworthy than their female counterparts. All they have to do is fall in line with the rest of the group, which, in fact, they have done for unknown millennia. Men may be less naturally trustworthy while they live, but if history tells us anything, they can certainly be trusted to die. By the same token, the more emotionally heightened disposition of the average woman, while making her less prone to trust, makes her the ideal candidate for creating stable environments, within herself and in the world, for fostering and nurturing the future of the human race. Again, forgive my generalities, but hopefully you follow. Now here’s how this relates to Ephesians…

Because wives are naturally trustworthy “on the ground,” Paul is calling them, in Christ, to rise and risk becoming more, to transcend and perfect their nature by trusting in their husbands. This is true femininity. Not to trust casually. Definitely not. Rather, to be careful and withholding of trust—to remain veiled toward the masculine—until the proper time of unveiling. And then…to trust. Again, trust is not intrinsically good. It depends on whom you trust. As I raise my daughters, I certainly do not teach them, “Now go and trust all men.” Of course not. What I actually say is, “Men are not generally trustworthy, so do not automatically give them your trust. Rather trust slowly and test for trustworthiness.” As Sean Penn’s character puts it in The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, “Beauty does not ask for attention.” But a time will come, when I may have to remind them of what St. Paul says to the Ephesians. “When you find a man who is trustworthy, and you promise yourself to him, you must trust him as though trusting Christ, though he is not Christ (and will, at times, let you down).” Of course, I won’t mean this as some static law, in every situation all the time, even if your husband turns out to be a serial killer, etc. But I will mean it to an uncomfortable degree. Because this is how reality works. After all, they have already put their trust in me, their imperfect father, in a similar fashion for similar reasons. And as we have said, that trust can actually engender the trustworthiness it seeks.

In our relationship with God, trust is the lens by which we see how truly trustworthy he is. In human relationships, the same is true, but even more so. First, trust opens our eyes to ways the other person may have already been trustworthy, which we could not see before. But second, our trust can actually beget trustworthiness in the other person. Thus the common saying, “She makes me want to be a better man.” There is something humbling and challenging about being trusted, which makes men want to live up to the trust they’re given. Feminine trust sets the stage, creates the space, for masculine trustworthiness to fill. All of this, of course, can be misused. I do not deny it. Trust is a dangerous game. Trusting the untrustworthy is a deadly game. And yet, there is no other game to play. Trust and trustworthiness is the currency of reality. If you do not trust, you cannot live.

Likewise, because husbands are naturally trusting “on the ground,” Paul is calling them to transcend and perfect their nature by proving themselves trustworthy for the sake of their wives. This is true masculinity. Not merely to be powerful, but to lay down your own power and agency for the sake of others by submitting to the trustworthy patterns of Christ. And notice how much more extreme Paul’s language is here regarding what men must do. This would have been counter-cultural in Paul’s day, for sure: “Husbands, love your wives, just as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her…”

I cannot stress this enough. If the message of the church is, “Wives, submit!” without the corresponding (yea, even greater) call for husbands to “give themselves up” for the sake of their wives and families, none of it works. Trust without trustworthiness is a death sentence. It is the same kind of disaster as unifying yourself to a false god who cannot provide what it promises. Husbands, then, must represent and imitate Christ, who always provides what he promises. They will, of course, do so imperfectly. But they must do so nonetheless.

In summary, Paul’s exhortation to wives and husbands is not merely a statement about nature but an exhortation to transcend what is natural to each. Furthermore, both men and women assume the feminine role with respect to God, that is, trust. The trust of wives toward their husbands and the trustworthiness of husbands toward their wives both constitute a deeper act of trust toward God. In this exchange of trust and trustworthiness, both parties offer themselves up to him as living sacrifices in two distinct yet complementary ways. And in this union of trust and trustworthiness, marriage becomes a living metaphor of the renewal of all creation.

Conclusion

Men and women are much more alike than they are different, of course. Both sexes must trust and both must be trustworthy if we are to be and become Christ’s body in the world, of course. Members of both sexes have equal value in this body, of course. And yet, the body of Christ is not made of merely homogenous interchangeable units, where each bears the same role and function as every other. In the kingdom of God, we are not mere numbered cogs in some modern democratic machine, but rather people, created male and female in his image; created with certain purposes, some of which we all share, some of which we share only with those of our sex, and some which seem uniquely given to each one of us. We are not so much “equal” as more than equal. Our value is found not merely in the fact of our being, but in our being and becoming exactly who he made us to be, as members of his body. We may discover in the end that our maleness or femaleness plays only a small role in that destiny. But since it was God and not we ourselves who created this gendered existence, it is worth asking anew what role it does play.

You may have noticed, I use this framework often (Heaven & Earth; Holiness & Inclusion; Atonement & Apocalypse; Trust & Trustworthiness). This is how I understand the Bible, as the reconciliation of opposites in Christ.

Ross, thanks so much for this piece! I think we may have talked a bit about it at SH at some point so it sounded familiar and is acting as a reminder for me to pray for trustworthiness and to live as a man who's yea means yes and no means no; to become a man trustworthy in thought word and deed.

I know this topic isn't completely related, but I wonder what this verse means in terms of leadership in church roles. I recently listened to a podcast about it and I still don't know what I think... Obviously another hot topic, one I understand not wanting to write about but......

My real question would remain this: Could we extend this transition from our human nature to a perfected nature (trustworthy-trusting for women (((generally))) and the reverse for men (((generally))) ) to the field of the church to say that we as a church aught to trust men as Pastors/Priests? (does that make sense?) Or is this verse much more centered around a marriage between two people and not so much to be thought about outside of that?

Sorry this was messy, but it's a legit question. The dude in the podcast I was listening to was using this verse to say that women should not be allowed to be pastors and I was just a little confused...

This hits differently when you frame it through the lens of responsibility and sacrifice rather than authority. Here's what I mean:

Picture an abandoned house at night. You and someone you love are standing at the threshold. Those creaky floorboards aren't going to test themselves. The dark corners need checking. Someone has to go first.

When you say "I'll go first, just hold onto me," that's not about being in charge. It's about being willing to take the risk before asking anyone else to. It's about checking for danger, testing the steps, making sure the path is secure. That's what Christ did for the church - He didn't just give orders from a safe distance. He went first, all the way to the cross.

And here's the thing: I'm intentionally not interpreting what this means for women, because that's not my lane to drive in. I don't have their processing capability, their lived experience, their perspective on Scripture. Maybe part of being trustworthy is knowing when to be quiet and listen.

When Paul talks about husbands loving their wives as Christ loved the church, he spends more time talking about sacrifice than authority. "Gave himself up for her" - that's the standard. Not "made all the decisions" or "stayed in charge," but "gave himself up."

As a guy, I've learned to refrain from telling women how to interpret their role in Scripture and more time wrestling with the profound weight of mine. After all, Jesus didn't just point the way to salvation - He became the way. He went first. He took the hits. He made the path safe.

That's what love looks like. That's what trustworthiness means. Not "I'm in charge," but "I'll go first into the dark, and I'll make sure it's safe before I ever ask you to follow."