The Cure for the Modern Cyclops

Owen Barfield On How To See The World In Stereo

Our sophistication, like Odin's, has cost us an eye, and now it is the language of poets, insofar as they create true metaphors, which must restore this lost unity conceptually after it has been lost from perception.

— Owen Barfield, Poetic Diction

The other week, I came across an intriguing quote from Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha in my Substack Notes (thanks to Dylano O’Sullivan)…

When someone is seeking,” said Siddhartha, “it happens quite easily that he only sees the thing that he is seeking; that he is unable to find anything, unable to absorb anything, because he is only thinking of the thing he is seeking, because he has a goal, because he is obsessed with his goal. Seeking means: to have a goal; but finding means: to be free, to be receptive, to have no goal. You, O worthy one, are perhaps indeed a seeker, for in striving towards your goal, you do not see many things that are under your nose.

After thinking on it for a bit, I wrote the following response:

This seems dead on with regard to obsessive goal orientation (e.g. the Cyclops myth). But the proposed solution—“to have no goal”—seems like an over-correction. What is actually needed is something like “seeing in stereo,” balancing focus with flexibility, left-brain specificity with right-brain generalization. The cure for the Cyclops is a second eye, another perspective on his obsession, which is not precisely the same thing as surrendering his obsession altogether.

This, by the way, becomes a major difference between Christianity and Buddhism. The Christian does not nullify his desires, but rather re-orients them toward the highest good. “Seek first the kingdom…and all these things will be added.”1

At the time of writing this, though I didn’t see the connection, I had been on a deep dive into the works of Owen Barfield, whose life’s work had to do with the problem of knowledge, or you might say, the problem of “seeing.” The problem, in part, as my opening quote suggests, is that the modern world has purchased a form of sophistication at the price of losing one eye. We still see, yet without depth perception (if you will forgive the pun). The solution, then, is to recover stereoscopic vision. But what, in our obsessive modern Cyclops world, is the eye we’re seeing with, and what is the eye we are missing? This, it turns out, is what Barfield’s work is all about, though again, I had not yet made this connection myself.

As you may recall, my last piece actually dealt with the problem of knowledge through C. S. Lewis’s essay “Myth Became Fact.” Lewis depicts the problem with a slightly different but overlapping framework: a divorce between meaning and fact, subject and object, concrete and abstract.

This is our dilemma—either to taste and not to know or to know and not to taste—or, more strictly, to lack one kind of knowledge because we are in an experience or to lack another kind because we are outside it. As thinkers we are cut off from what we think about; as tasting, touching, willing, loving, hating, we do not clearly understand. The more lucidly we think, the more we are cut off: the more deeply we enter into reality, the less we can think. You cannot study pleasure in the moment of the nuptial embrace, nor repentance while repenting, nor analyze the nature of humor while roaring with laughter. But when else can you really know these things? ‘If only my toothache would stop, I could write another chapter about pain.’ But once it stops, what do I know about pain? Of this tragic dilemma, myth is the partial solution.”

— C. S. Lewis, “Myth Became Fact” (1944)

Now, what I failed to mention in my last piece is that one of Lewis’s closest friends, Owen Barfield, a fellow “Inkling” along with Lewis and Tolkien, was wrestling with this same dilemma long before Lewis and, in fact, made it the subject of his entire academic career. Barfield’s most well-known work and my favorite non-fiction book of 2024, Poetic Diction, was actually dedicated to Lewis in 1928, three years before Lewis even converted to Christianity. Needless to say, Lewis’s own understanding of the problem owes much to Barfield’s influence.

Anyway, for weeks now, I have been meaning to write an essay introducing Barfield’s thought. Then, just as I was beginning to organize it, I came across a 2016 lecture from the brilliant Malcolm Guite (whom I have discovered far too late—thank you, Jim Van Eerden) entitled “Owen Barfield: Knowledge, Poetry, & Consciousness,” and I was stopped in my tracks. Not only does Barfield’s work deal with exactly the problem of one-eyed vision which I had been contemplating, which plagues our modern perspective on reality, but Guite’s concise introduction to Barfield packed such a punch, that it made me rethink the whole idea of writing my own introduction. Why would I do that when I could instead guide you, dear reader, to someone who has already done it, and done it far better than I ever could?

So, without further ado, I present to you Malcolm Guite’s introduction to the philosophy of Owen Barfield, which, I remind you, profoundly shaped the thought-life of C. S. Lewis and may indeed point to the cure for the “meaning crisis” in which we now find ourselves. And, as a supplemental guide, I have copied and organized all the actual quotes from Barfield which appear in Guite’s lecture below, because I believe they tell the story almost on their own. Beyond that, I have added a few comments here and there for context, and some concluding remarks. Enjoy.

Intro to the Meaning Crisis:

Amid all the menacing signs that surround us in the middle of this 20th century, perhaps the one that fills thoughtful people with the greatest foreboding is the general sense of meaninglessness. It is this which underlies most of the other threats. How is it that the more able man becomes to manipulate the world to his advantage, the less he can perceive any meaning in it?

— Owen Barfield, “The Rediscovery of Meaning” (1977)

The Alienation of Man (From Nature, From Self)

The vaunted progress of ‘knowledge’, which has been going on since the seventeenth century, has been progress in alienation. The alienation of nature from humanity, which the exclusive pursuit of objectivity in science entails, was the first stage; and was followed, with the acceptance of man himself as part of a nature so alienated, by the alienation of man from himself. This final and fatal step in reductionism occurred in two stages: first his body and then his mind. Newton’s scientific traditions, a form of behaviorism; and what has since followed has been its extension from astronomy and physics into physiology and ultimately psychology.

— Barfield, “The Rediscovery of Meaning” (1977)

Here, Guite references the poetry of Sir John Davies, which, at the end of the 16th Century, still saw the cosmos as a dance tingling with consciousness, much like Dante’s encapsulation of Aristotle: “the love which moves the sun and the other stars.” The world was full of conscious agents, not mere things, and love was the energy between them. Contrast this to Newton’s view, a world made of entirely inanimate objects working on a law of gravity. What was once a cosmic dance of love is reduced to “a set of small items batting about meaninglessly together in the void.”

Guite: “But people said, ‘Never mind, at least we have this rich and suggestive inner life ourselves, so we’re fine.’ And then, we see our bodies as part of that. Finally, this attention turns to our brains, and precisely because we have avoided what is out there in terms of consciousness, we find no means of giving an account of what is in here—the consciousness within. The alienation of nature is followed by the alienation of the body and, ultimately, the mind itself.”

The Disintegration of Knowledge in Science

Science, with the progressive disappearance of original participation, is losing its grip on any principle of unity pervading nature as a whole. The knowledge of nature—the hypothesis of chance—has already crept from the theory of evolution into the theory of the physical foundation of the Earth itself. But more serious, perhaps, than that, is the rapidly increasing fragmentation of science. There is no science of sciences, no unity of knowledge; there is only an accelerating increase in that pigeon-holed knowledge by individuals, of more and more about less and less.

— Barfield, Saving the Appearances (1957)

Reinforcing this point, Guite quotes T. S. Eliot: "Where is the knowledge we have lost in information? Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?"

Here we are introduced to Barfield’s theory of the evolution of consciousness. In a word, our current detached mode of knowing—the kind which has allowed us to make spaceships and iPhones and seemingly translate the whole world into zeros and ones, but also the kind which has alienated us from nature and self—is only a phase; it is not what it used to be, and it is not necessarily what it must be. By reaching into the past, we may perhaps glimpse other modes of knowing—not dead but dormant in us—which may help us to reintegrate ourselves.

Guite: “This approach gives us the possibility of imagining another way of knowing—a way that does not necessarily exclude our present hard-won objectivity but rather integrates it with a more participative and meaningful way of knowing.”

Learning To “Read” The World Again

“It remains to be considered whether the future development of scientific man must inevitably continue in the same direction, so that he becomes more and more a mere onlooker, measuring with greater and greater precision and manipulating more and more cleverly, and thus growing spiritually more and more strange. His detachment has enabled him to describe, weigh, and measure the processes of nature and to a large extent control them, but the price he has paid has been the loss of his grasp of any meaning in either nature or himself. Penetration to the meaning of a thing or process, as distinct from the ability to describe it exactly, involves a participation by the knower in the known. The meaning of what I am writing is not the physical pressure of thumb and forefinger or the size of the ink blots with which I form the letters; it is the concepts expressed in the words I am writing. But the only way of penetrating to these is to participate in them—to bring them to life in your mind by thinking them. In the same way, if we want to know the meaning of nature, we must learn to read as well as to observe and describe.”

— Barfield, “The Rediscovery of Meaning” (1977)

The image is simple enough: language as a metaphor for reading the whole world. The absurdity of studying ink blots and paper particles in order to glean an author’s meaning has its parallel in much of our modern scientific analysis of the world around us. Of course, such study has its benefits, but it has come with the cost of forgetting how to read any meaning into those same objects of study. I cannot help but include this lovely bit of verse from Coleridge, which Guite quotes at this point:

But thou, my babe! shalt wander like a breeze By lakes and sandy shores, beneath the crags Of ancient mountain, and beneath the clouds, Which image in their bulk both lakes and shores And mountain crags: so shalt thou see and hear The lovely shapes and sounds intelligible Of that eternal language, which thy God Utters, who fro eternity doth teach Himself in all, and all things in himself. Great universal Teacher! he shall mould Thy spirit, and by giving make it ask.

Language: The Living Fossil Record of Our Souls

It has only just begun to dawn on us that in our own language the past history of humanity is spread in an imperishable map, just as the history of the mineral earth lies embedded in the layers of its outer crust. But there is this difference between the record of the rocks and the secrets that are hidden in language. Whereas the former can only give us knowledge of outward dead things, such as forgotten seas or the bodily shapes of prehistoric animals, language has preserved for us the inner living history of man’s soul. It reveals the evolution of consciousness.

— Barfield, History in English Words (1926)

Guite: “He wrote that in 1926, and in a sense, everything he has written since is a development of that insight: that our current mode of consciousness is not the same as it was when the words we are now using were first used, nor will it remain the same. We can learn from a previously participative, meaning-drenched way of understanding and perhaps learn to recover a participative way of knowing. The period in which we happen to be living, in which we experience knowledge as detached and alienated, is only one fragment of time. But Barfield contends we carry, all of us, within us, embedded in the language we use, the memory of another way of seeing the world. That is one of Barfield’s core ideas: that by finding out what words used to mean, you can get a different view of consciousness itself.”

Words which for us today have an outer meaning only formerly had an inner meaning as well. Moreover, the process by which they have lost their inner meanings is clearly the obverse or correlative of the very process by which many other words have lost their outer meanings. Both processes may well be illustrated by the history of such terms as breath or air or wind and spirit. For here they happen to be sharply pointed by a well-known record from a period when they were not as yet divided. In the English version of St. John's Gospel, we find the following three verses, in which both terms—air, wind, breath, spirit—are employed alternately:

That which is born of the flesh is flesh; and that which is born of the Spirit is spirit. Marvel not that I said unto thee, Ye must be born again. The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, or whither it goeth: so is every one that is born of the Spirit. (John 3:6-8)

Probably most people read the first part of verse 8 as a metaphor comparing the Spirit with the wind, but if we turn to the Greek, we find it is not so. The same word, pneuma, is employed throughout, though it has been rightly translated first as spirit, then later as wind, and then again as spirit. In Hellenistic Greek, pneuma still conveyed the concomitant meanings of both. But the English translators had to split it into two words: one of which—spirit—has since lost its outer meaning. When we see that in earlier life and culture, they didn’t need two words for those two things, but insisted on one word for both, we recognize that they were apprehending a unity, which we’ve lost.

— Barfield, Speaker’s Meaning (1967)

In other words, “spirit” has lost its outer meaning, existing for us as little more than an abstract concept with little to no concrete manifestation in our world, whereas “wind” has lost its inner meaning, existing for us only as a measurable meteorological event. In “wind” and “spirit” we now perceive two distinct realities for what once was apprehended as a unified whole.

Poetry as a Means of Reintegration

I find myself obliged to define poetry as a felt change of consciousness, where ‘consciousness’ embraces all my awareness of my surroundings at any given moment, and ‘surroundings’ includes my feelings. By ‘felt’, I mean to signify that the change itself is noticed or attended to.

— Barfield, Poetic Diction (1928)

Later, in the same work, Barfield elaborates on this notion:

“The phrase [the moment of appreciation] must be taken with some exactness. Appreciation takes place at the actual moment of change. It is not simply that the poet enabled me to see with eyes and so to apprehend a larger and fuller world, but the actual moment of the pleasure of appreciation depends upon something rarer and more transitory. It depends upon the change itself. If I pass a coil of wire between the two poles of a magnet, I generate in it an electric current, but I only do so while the coil is positively moving across the lines of force. Current only flows when I’m bringing the coil in or taking it away. So it is with the poetic mood, which, like the passage from one plane of consciousness to another, lives during the moment of transition and then dies. And if it is to be repeated, some means must be found of renewing the transition itself.”

—Barfield, Poetic Diction (1928)

For Barfield, the reading of great poetry could lead to an actual change of consciousness, a felt participation in an otherwise hidden reality, where subject and object are re-unified after a long divorce. But this reunion lasts only as long as the encounter itself, and then fades. Guite suggests here that great poetry—particularly ancient poetry and other ancient texts—can be for us a kind of telescope that allows us to see far beyond the limits of our natural scope, but only as long as we are using it as our lens. “The access to forgotten truths which such a change of consciousness enables,” says Guite, “is vital as a counterbalance and corrective to the one-eyed view of reductive science.”

The Cure For One-Eyed Vision

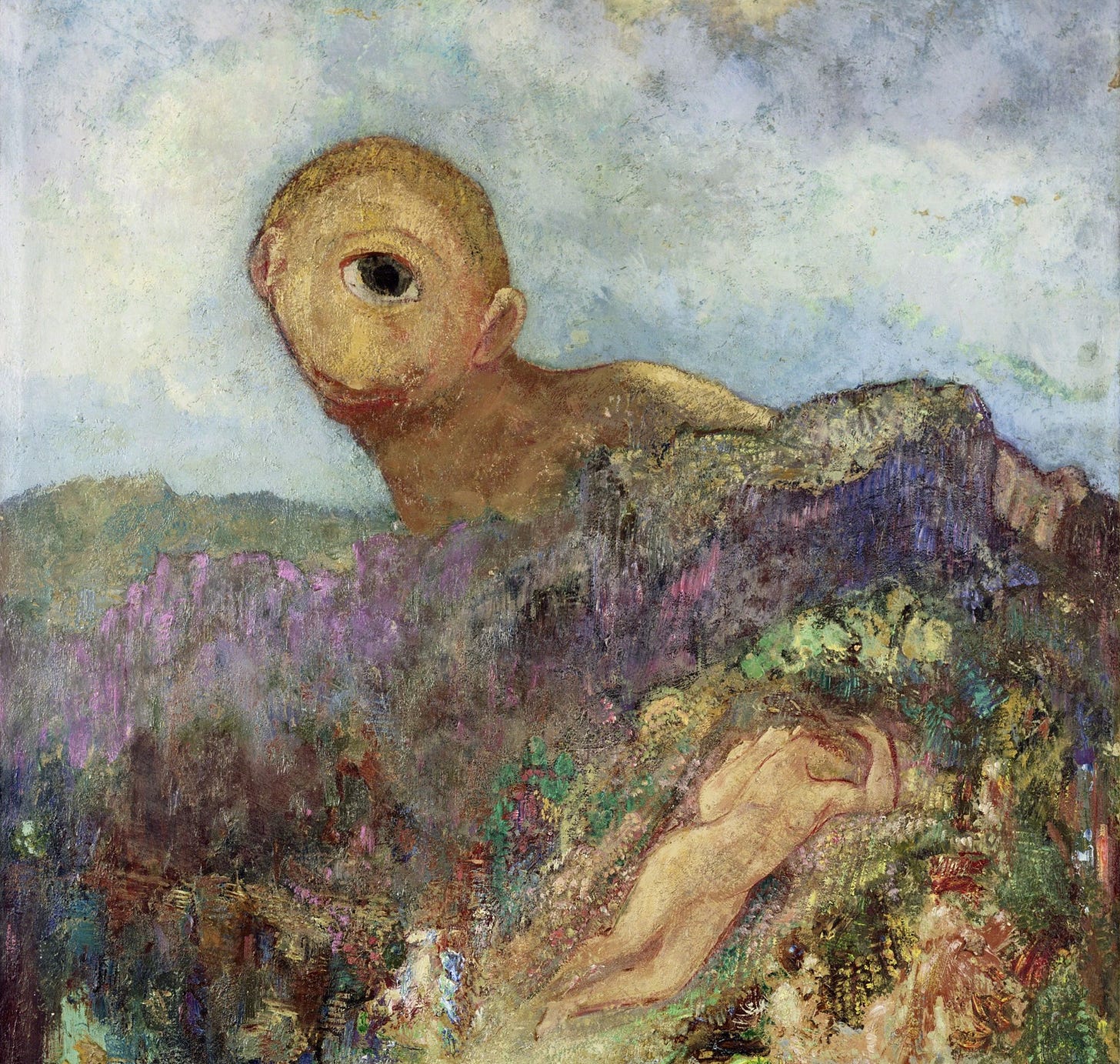

Guite: “Just as poetry and poetic metaphor gave us access to this change of consciousness, so too, going behind the poetry—the earliest poetry, the whole realm of myths and mythology—also have something vital to teach us. Indeed, Barfield appeals to myth, particularly to the story of Odin, later in Poetic Diction, to make this very point…In order to acquire knowledge, Odin made a sacrifice: first hanging himself on the world tree, Yggdrasil, the great ash tree that connected the nine worlds of Norse mythology, and then descending to its roots and offering to pluck out one of his own eyes in return for the knowledge of how to interpret the runic letters which the tree was writing with its roots. So, Barfield says this about modern science, an extraordinary application of the myth, but very pertinent:

Our sophistication, like Odin's, has cost us an eye, and now it is the language of poets, insofar as they create true metaphors, which must restore this lost unity conceptually after it has been lost from perception.

— Barfield, Poetic Diction (1928)

Guite concludes, “We see things that perhaps could not be seen in other ages, but only by plucking out one of our eyes.” Exactly.

Without the continued existence of poetry, without a steady influx of new meaning into language, even the knowledge and wisdom which poetry herself has given in the past must wither away into a species of mechanical calculation. Great poetry is the progressive incarnation of life into consciousness.

— Barfield, Poetic Diction (concluding paragraph)

Meaning in the modern world is a cut flower. It still survives in our language. It still operates in the deeper software of our moral intuitions, guiding our relationships to others and to the world around us at a subconscious level. But what is already subconscious is becoming dormant. And what is dormant within us is dying due to atrophy. The world around us appears increasingly spiritually dead (meaningless), which reflects back on our sense of self, which reflects back on our perceptions of the world, etc. Thus, our spiraling feedback loop of disenchantment. But, as Barfield concludes, great poetry can re-infuse life into our consciousness.

A New Science: Redeeming Imagination & Participation

Guite: “There’s a passage in the preface to the second edition of Poetic Diction which argues for a new science, a new way of seeing on the basis of what we've discovered through these languages…”

Science deals with the world which it perceives, but seeking more and more to penetrate the veil of naive perception, progress is only towards the goal of nothing, because it still does not accept in practice whatever it may admit theoretically, that the mind first creates what it perceives as objects, including the instruments which science uses for that very penetration. It insists on dealing with data, but there shall be no data given save the bare percept. The rest is imagination. Only by imagination, therefore, can the world be known. What is needed is not only that larger and larger telescopes and more and more sensitive calipers should be constructed, but that the human mind should become increasingly aware of its own creative activity.

— Barfield, Poetic Diction (preface to the 2nd Edition)

Modern science has tried systematically to erase the subject from the act of knowing. What is “objective” is said to be trustworthy and true, what is “subjective” is said to be a contamination of the data. But, as Barfield points out, there is no data without the subject which perceives and organizes it, not to mention chooses what to put under the microscope in the first place. We have known this, Guite reminds us, since Kant. What we see through the microscope and telescope is not pure reality. Our minds must still “connect the dots.” Any physicist will tell you that the table before you is mostly made of space. Our conscious minds—our imagination—must do the work to make it as it appears to us, to make it what it is to us. Any quantum physicist will tell you that the observer inevitably affects the thing observed. Nothing exists purely objectively. Though we may torture the English language all we want by use of the passive voice, says Guite—"the litmus paper was immersed into the titration and it was observed that…”—the subject cannot be erased. There is no experiment, indeed no knowledge at all, without him.

Guite: “Barfield is saying, if our perceiving mind is actually part of what's there and part of how we know what's there, and part of what shapes what's there, then actually the imaginative part of our perceiving mind might be the most important part. We might even have some responsibility for the way we choose to imagine the world. The way we choose to configure the world might have some considerable influence on what it is and how we treat it.”

To further explain this point, Barfield uses the example of a rainbow. Is a rainbow “really there” if it’s appearance depends upon the observer? Of course, the rainbow is not there in the same sense as the water droplets are there. But its appearance can still be confirmed by multiple independent observers. The rainbow, in other words, is a collective representation.

Just as a rainbow is the outcome of the raindrops and my vision, so a tree is the outcome of the particles and my vision and my other sense perceptions. Whatever the particles themselves may be thought to be, the tree as such is a representation. And the difference for me between a tree and a complete hallucination of a tree is the same as the difference between a rainbow and a hallucination of a rainbow. In other words, a tree which is really there is a collective representation.

— Barfield, Saving the Appearances (1957)

Guite: “Now, this distinction between particles and representation—and the corollary from it that all phenomena or appearances are representations, and therefore all appearances are at least in part the creation of the human mind— informs everything else that Barfield says. For he argues that although this distinction is theoretically accepted both in philosophy and physics, it is, for all practical purposes, completely ignored when we come to do our biology or our geology.”

The greater part of this book consists of a rudimentary attempt to remedy the omission of the man-nature relationship. But this involves challenging the assumption that the man-nature relationship has remained static. The result and really the substance of this book is a short outline or sketch for a history of human consciousness, particularly the consciousness of Western humanity during the last 3,000 years or so.

— Barfield, Saving the Appearances (1957)

If our consciousness is not fixed but changing, then perhaps the appearances of things in the world are also changing over time, says Barfield.

Guite: “Now that’s really radical. That, for a moment, gives you the exciting thought that when Homer sees Neptune rising out of the sea, or when he perceives the gods of the winds in the air, it’s not that he saw the dull things that we see and invented a god. He saw the god! That the very shaping of the mind shaped the thing. That there was an exchange between that extraordinary, numinous—not only meaning-drenched but person-drenched, personal, relational, multi-conscious world of the gods and the angels—that, actually, they really saw that stuff. […] Participation is the opposite of alienation. And what he begins to suggest towards the end of that book is that we can begin to move towards a more participatory mode of seeing the world.”

Is A Paradigm Shift Imminent?

Just as the Copernican Shift was a leap for our understanding of the cosmos, we are due for another leap in our own time with regard to our understanding of consciousness. The Cartesian paradigm—the split between mind and matter—is due for upheaval. But such “leaps” do not come easily. They are generally preceded by an overwhelming sense of crisis and desperation. Why aren’t the pieces fitting together?

Guite: “We cannot account for consciousness simply mechanistically. But we’ve got such a huge investment in a purely reductive and mechanistic way of seeing things, that every time we get any kind of observational phenomenon that doesn’t fit with it, we just ignore it. But there comes a point where there are too many to ignore.”

The frozen mass on which the psychological and physical structure of our technological civilization is erected—and into which are embedded deep down foundations, determining even the minor details of the edifice they support— that mass consists of a collective conviction, mainly subliminal, and by now amounting to a certainty, that nature is an objective system, which man can only affect by manipulation from without and that each individual man is a separate part of that kind of nature. That is the mass. And its surface at first sight looks firm enough. Yet for those without eyes to see, there are a good many indications that it is not nearly as firm as it looks. And further, that the likelihood of the mass as a whole continuing solid is being seriously threatened, both from above and below. Cracks are appearing in the surface where the foundation first became visible to the naked eye as the result of impacts from above, while from the opposite direction, the frozen mass itself appears to be growing thinner, becoming more like the crust than a mass, as it is thawed by a gradual increasing warmth rising from the depths below. The impacts from above represent the instinctive human reactions against the results of our uncritical objectivity that has dominated intellectual life for the last two or three centuries. The warmth from below represents the beginning of the criticism.

— Barfield, “The Coming Trauma of Materialism” (1976)

Conclusion

We creatures of the modern world, we are the Cyclops. We are the one-eyed Odin. Our one-eyed obsession has given rise to the world we now live in, with all its god-like accomplishments and comforts, but also with its narrowed vision of the cosmos and even of the human person. The solution is not merely to revolt against all science, objectivity, and technological advance—which would be only to pluck out the other eye—but rather to seek to restore an older way of seeing alongside the new. This older way of seeing is embedded in our ancient myths and poems, embedded in the Holy Scriptures and in our Christian tradition, hidden even in our very language. Our current meaning crisis is a sign of the need for a paradigm shift, if not a sign that the shift itself is imminent. The era of spectating and manipulating the world from outside only is reaching an impasse. An era of renewed participation is within reach, and in my view, the Christian Church, the Body of Christ, is the place where such a renewal could and must finally become a reality.

If you enjoyed this post, please hit the LIKE and RE-STACK buttons below. It helps a ton. To receive future posts to your inbox, please SUBSCRIBE. Thank you.

Barfield is the topic of this essay, but he’s not the only one tackling this problem. Scientist and philosopher Iain McGilchrist has in many ways taken up Barfield’s torch with his work on left-brain and right-brain thinking. For him, modern man has become a left-brain Cyclops, for which the solution is reintegration of the right-brain. For another contemporary parallel to Barfield’s work, see David Bentley Hart’s latest, All Things Are Full of Gods, which, at least in part, is a more detailed and forensic working out of much of Barfield’s thesis.

Morning Ross, if you haven’t already, you might be interested to read the short book by Peter Kreeft, the three philosophies of life. In it he explores Ecclesiastes, Job, and Song of Songs. I haven’t read it recently but it reminds me a little of your thinking here but from a different perspective. I must read it again!

https://archive.org/details/peter-kreeft-three-philosophies-of-life/page/11/mode/2up

You mentioned stereoscopy which brought this quote from my favorite philosopher, Matthew B. Crawford, to mind:

“Maybe the afterlife isn’t only a proposition about what happens to you after you die, in the narrow sense of a sequence. Maybe it’s something always present — an afterlife, if you will, in which all life is set, a separate-but-not-separate dimension that reverberates in and saturates the present. Having one eye on this life and one on eternal life results in a kind of stereoscopy, which you need for depth perception, to see the present world in its fullness.”

He’s speaking into a different context, but he’s thinking of stereoscopy as an epistemological faculty which seems to resonate with what you and Barfield are getting after.

It also occurs to me that Odin lost an eye, and yet he had Huginn and Muninn who go about and bring him information. I wonder if our monoscopic vision is the price for endless information delivered to us.

I wonder if myth/poetry and eternal life/eschaton are of a piece and a joint renewal of our stereoscopy.