Whoever Would Be Great

5 Signs of a True Leader

This summer I’ve been meditating on the Christian understanding of authority, especially as it relates to Jesus’s enigmatic statement, “You will say to this mountain, ‘Move from here to there,’ and it will move,” and it has been blowing my dang mind. The question I keep coming back to is a simple one, but the implications feel earth-shattering (no pun intended): How does one move a mountain or calm a storm or heal a paralytic with a word? What kind of faith can achieve such things? In quantitative terms, we’ve been assured that no more than a mustard seed is necessary. But what of the quality of such faith?

I propose the quality is that of authority, not to be confused with power. Authoritative faith speaks to the rock rather than striking it. Jesus does not overpower the storm. He simply tells it to be still. That is what amazes the disciples: “Who is this that even the wind and the waves obey him?” Whereas power ignores or diminishes the agency of the other, proper authority restores and redeems agency by calling the other—be it a person, a demon, or a storm—to submit to that which is higher. Of course, you can always strike the rock, and it may very well still produce water. Most of the modern world is proof of this in one way or another. But what you find later on is that such methods often cost you the Promised Land. The forbidden fruit is still edible to those who take it out of turn, but it doesn’t give them what they hoped it would in the end. My thesis is this: Authority—that is, patient dominion over natural and spiritual realities via relationships of trust (picture St. Francis asking the birds to stop singing so he can finish his sermon)—is a lost art in our time, both in Christian and in secular spaces. But if we could reclaim it, perhaps we still could move mountains with a word. I’m dead serious.

Anyway, rest assured, there’s a weird, deep-dive essay coming soon for those interested. In the meantime, I thought I’d introduce the subject of authority with a much more straightforward piece on leadership.

What makes a good leader?

First, let’s admit that today “leadership” is a bit of a buzzword. I am the teaching director for a faith-based leadership program for young 20-somethings, and even I hardly know what people mean by it most of the time. The term “leadership” has remained impressively fashionable even as related terms like “authority” and “hierarchy” have fallen out of favor. It’s honestly strange. Grown men and women who show precious little respect for their own bosses, pastors, parents, and local authority figures, do not hesitate to sign their children up for “leadership” programs and opportunities in their schools and elsewhere. But why? Is it a cynical ploy to give their own children the corrupting reigns of power before someone else lords it over them? Or are they really holding out hope that somehow the next generation will redeem our tenuous relationship to authority? If so, how?

In the church, we speak of “servant leadership,” which ideally reflects Jesus’s teaching on the subject:

You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their great ones exercise authority over them. It shall not be so among you. But whoever would be great among you must be your servant, and whoever would be first among you must be your slave, even as the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many. — Matt. 20:25-28

Yet, as you may have noticed, Jesus is often misunderstood on this point, and not merely by non-Christians. Many pragmatic Christians have sought to become “great” not by serving but by—well, by simply becoming great—and ministering from that high place. Without necessarily compromising their morals, the pragmatic types tend to follow the world’s path to power and influence in order, then, to use that power and influence for Christ, doing as he would do. To be fair, I’ve seen enough success in this realm not to be totally cynical about it. But it’s at least worth acknowledging that this is not what Christ did. When the people tried to make him king by force, he fled.

On the other hand, there are those who so flee from the very idea of authority that, for them, the term “servant leadership” means little more than servitude. Don’t get me wrong. Serving others is a noble calling. But that doesn’t make it leadership. When James and John tell Jesus they want to sit at his right and left in the kingdom, he does not say, “Do not wish to become great. Rather, serve.” Instead he tells them that they have misunderstood the meaning of greatness and the means of becoming so: “You do not know what you are asking…Whoever would become great among you must be your servant…even as the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve…” In other words, Christ does not merely replace greatness with servitude. He proposes a deeper union of the two. Those who wish to become great must do so by becoming low, just as Christ himself came to serve and, through serving, became Lord of all.

All disciples of Christ must become servants. Ironically, good leadership may in fact be the lowest (and therefore highest) form of servanthood. Without leaders—without fathers, mothers, teachers, coaches, pastors, elders, mentors—we would have no one to look up to, no one to learn from, no one to follow, no one to count on, no one to guide and protect us. It may sound strange to our egalitarian ears, but we all secretly long to look up. We need someone to be great, someone to be above us, lest we all fall down. And yet, when those above us let us down, we fall all the harder.

Whenever I teach on this subject, I ask my students at the beginning of class to think of one experience they’ve had with a good leader. Then I ask them to do the same with a bad leader (someone either ineffective or untrue to their office). As they share their experiences, two things become inevitably clear: First, leaders are crucial in shaping our lives and our souls, for better and for worse. Second, good leaders really are servant leaders, putting themselves as far below us as they are above us.

What I am proposing is that “servant leadership” is not just a Christian brand of leadership, like Christian rock music or Christian bookstores. Servant leadership is the only true, sustainable form of leadership. Christ’s warning applies as much to secular CEOs and Presidents as it does to you and me. The Gentiles may lord it over us for a time, but in the end, even Rome has a Pope where it once had an Emperor. It seems strange to call it a law of nature, but I believe it is: Whoever wants to be first, must be slave of all. To be great is to be a great blessing to others. Otherwise your so-called greatness is living on borrowed time. In leadership as elsewhere, only love is sustainable. Everything else is a resounding gong or a clanging symbol.

5 Signs of a Leader

I don’t tend to read leadership books, but I have been blessed with a number of truly great leaders in my life. These are my observations on what makes them so. If I’m simply repeating the points those books are making, well, here they are again but shorter and for free. If not, I’m pretty sure this is what those books should’ve said (and it’s still free). Here goes.

1. Articulate Purpose

This one should be the most obvious. A good leader shows you what to aim at, and shows it to you clearly. If there is confusion about the goal, it’s going to be very hard to get there, much less to get there together. Notice that this also makes the leader a servant. When the purpose is stated clearly, even the leader becomes subject to it. You are not merely following him. You are following what he is following. “Very truly I tell you, the Son can do nothing by himself; he can do only what he sees his Father doing, because whatever the Father does the Son also does” (John 5:19). Every good leader has a purpose above and beyond himself, to which he is devoted. If your leader does not know his purpose or cannot state it clearly, this is cause for concern.

2. Assume Responsibility

It is not enough to state a purpose. The leader must be the one who bears the brunt of the responsibility for seeing it through and who bears the most blame if/when it fails. There’s an old (seemingly fading) tradition of corporate CEOs announcing their resignation when the company fails in one way or another. The failure may not have originated at the top. It often doesn’t. The main cause may have been located so far down the chain of command that the CEO did not and could not have even known about it before it was too late. Still, traditionally, the leader takes the wrap. And this is more than just symbolic. It comes from an understanding that those at the top are responsible not only for the top but for the whole stack. Every level.

Imagine that I, as the father of a household, declare to my family that we are going to rehab the whole backyard. Let’s say it’s a total mess. Hasn’t been touched in years. There’s vines and weeds and thorns growing in every direction. You can’t even see the ground. But we are going to transform it, I say. Okay, my purpose has been stated. But then, two weeks later, I find myself giving my eight and eleven-year-old sons (the help) a hard time because we haven’t even made a dent. Who’s fault is that? Who is most responsible? Well, they were pretty incompetent. I’d shown them how to start the lawn mower a hundred times, but they still couldn’t do it. Or perhaps they were lazy. They had the capacity to do the job, but they just chose to play video games instead. Maybe there was a misunderstanding. Their mother told them to clean the house before they started on the yard. My sons may be at fault (especially with the video games), but at the end of the day, it’s my fault fundamentally. I am the leader, and therefore the lowest as well as the highest. Even their fault is ultimately my responsibility (without ceasing to be theirs).

I run a surfing camp for a living. At the start of each summer, I remind all my staff that they are taking campers’ lives into their hands every time they step foot in the ocean with them. “The stakes are that high. The ocean does not mess around.” It’s admittedly a lot for a 19-year-old to bear, but I want them to feel and share the burden of responsibility. But that’s not all. My staff also know that I am their covering. If something goes terribly wrong, if someone needs to be held accountable, that person will always be me first and foremost. It’s my job to make sure they are fully equipped to do their job. If they fail, I have failed, and I am the first to blame. Everyone knows this. It would be an unsustainable job if they didn’t. Leaders assume responsibility.

3. Provide A Plausibility Structure

This is probably the most difficult and most technical aspect of good leadership. It may also be the most underappreciated, as far as I can tell. In a word, good leaders make a way. In many modern ventures—even in the church—you tend to see a lot of navy-seal-type leaders looking for navy-seal-type followers: “You gotta want it!” It is tempting to imagine that good leadership is mostly just about getting people from A to B by means of motivation and inspiration. Sure, motivation matters. But in most cases, the ground between A and B is a freaking wilderness, and all the motivation in the world won’t keep your people from getting lost in it. Humans need plausibility structures. Even navy seals have plans, traditions, procedures, and protocols. In fact, they’re famous for it.

Between every A and B that’s worth the journey, there is a very specific and usually pretty technical problem that needs to be solved. And the problem often requires real patience and humility to grasp. You may even need to get lost in it yourself for a while before you can effectively show someone else the way through, before you can make and mark the way for others. It’s nearly impossible, especially for a whole group of people, to traverse a wilderness without a path. Even when a path exists, it’s hard not to lose our way once or twice, sometimes so much so that we’re tempted to turn back. Good leaders cut clear paths so that others can follow them through the wilderness. Path-finding is the work of pioneers. Path-cutting is the work of servants. Both are the role of a true leader. “Turn left here.” “Wait til morning to cross this section.” “You’ll need extra supplies for that stretch. I didn’t have them the first time, but you will now.” This is leadership.

Returning to the backyard rehab, my boys need to see me using the mower for this purpose and the chainsaw for that. They may even need to put their hands on top of my hands the first few times they use the tool. To feel it when it’s running well and to feel when it isn’t. (Not that I’m teaching my eight-year-old how to use a chainsaw. You can’t prove that I did that.) They need to taste and see the plan, not simply to hear it from my lips. If I have shown them it is possible, they have an infinitely better chance of succeeding when they try to do it themselves. If I am doing it with them, perhaps all the more so. But more on that in point #5.

4. Balance Focus with Flexibility

I mentioned in point #1 that effective leaders become the servants of their stated purpose. This is generally a good thing and keeps the whole organization centered and driven towards a common goal. But there is also such a thing as becoming enslaved by your stated purpose, and enslaving others in the process. Overly single-minded leaders often become blind to the whole complex of limiting factors and constraints to which their goal is inevitably subject. And the more seemingly noble the goal, the more this danger is evident, which is why obsessive ideologues often do more damage at the helm than mere narcissists.

Of course, in the modern world, stubborn focus is often seen as a virtue rather than a vice…and for understandable reasons. Certain heights would never be reached if it weren’t for the courageous insistence of bold, single-minded leaders. We often celebrate these Captain Ahabs, these Cyclops-leaders as our best and brightest, forgetting that such stories don’t often end well. Achieving great purposes, especially as a team, requires more than just great drive and determination, more even than great plans and plausibility structures. It requires the wisdom to know when and how and how much to pivot from your original formula.

Almost nothing worth doing can be done in a straight line. And the primary limiting factor that often requires zigging and zagging is the people under your care. This applies to parents, coaches, and teachers as well as to CEOs and military commanders. The people you lead are the ones who, while possibly sharing your mission in a general sense, often cannot see the end as clearly as you and cannot run as fast or as far. That’s at least part of what makes you the leader and not them. You can, of course, keep spurring them on until they hit a wall and quit, until they no longer share your mission or no longer trust your leadership. (And will that have been their fault or yours? See point #2.) Or…you could pause and ask yourself, “How can I become their servant rather than making them my slaves? How can flexibility and forgiveness at this moment lead to further and deeper focus on our shared task in the end?”

In the Bible, God often introduces these pivots, these zigs and zags, at crucial moments in his redemptive plan. His overall aim does not change, of course. But when his people consistently fail to come alongside him, he allows for surprising detours. He introduces new ways, new paths for the sake of realignment. Flexibility and forgiveness, it turns out, are fundamental to success. Even when your initial purpose and plan are flawless, as in the case of our Lord, flexibility is needed. But our own purposes and plans are not flawless, so we should be all the more ready to pivot. Good leaders balance focus with flexibility.

5. Prove Yourself Trustworthy

Perhaps the most basic thing every leader must learn is that trust and trustworthiness are the fundamental currency of existence. The world, of course, would say otherwise. When even human beings are seen as objects to be moved this way and that, power becomes the dominant currency. But the Bible, from its very first chapter, insists on a different reality. Not even things are things to God. In the beginning, not only human beings but all creation is endowed with a kind of agency or capacity for relationship. Even the fish and birds—even the sun, moon and stars—are given jobs and jurisdictions. The whole created order, it would seem, has been set in motion not by a clock-maker but by an active, loving Father who expects a loving response. That’s the kind of leader God is. Dante was right when he said love was the true name of the gravity that moves the sun and the other stars. Power is subservient to love, even for God.

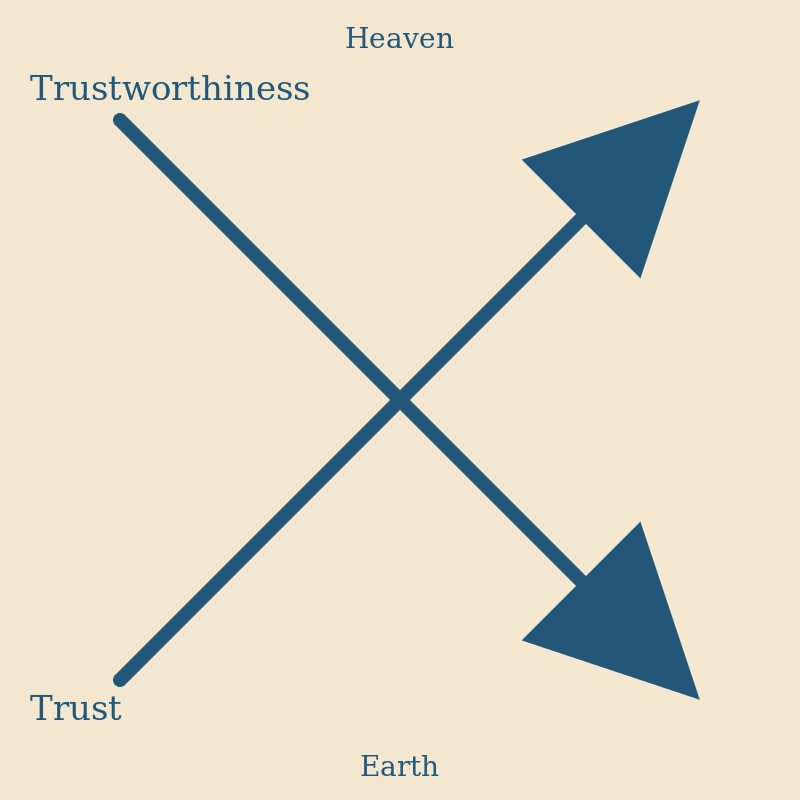

Now, trust and trustworthiness are something like the left and right hand of love; they are the way that love operates in the world. The whole Bible can actually be seen as an X-shaped story of trust and trustworthiness, where trust begins at the bottom-left and moves upward from earth to heaven and trustworthiness begins at the top-left and moves downward from heaven to earth. Love is made complete at the center of the X, the marriage of heaven and earth, the perfect union of trust and trustworthiness. The same, by the way, can be said of any organization. All who submit must trust, and therefore all who lead must prove themselves trustworthy. In the Old Testament, the Lord is the one who continually proves himself trustworthy while continually pleading with his people to trust him. This is even how he identifies himself at the beginning of the Ten Commandments:

“I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of Egypt, out of the land of slavery. You shall have no other gods before me.” (Exodus 20:2-3)

Trustworthiness, trust.

Let’s imagine, in my backyard rehab project, that I have stated the purpose clearly, that I have made myself the responsible party, that I have provided a plausibility structure to get the job done, and I have been sensitive to the constraints of my family members, making the appropriate concessions at the appropriate times for their sake. But somehow, after all that, the project is still doomed. We just never finish it. Why? I’m tempted to blame it on others, but the fact is, it was a big project, and I just couldn’t engender enough motivation, devotion, skill, teamwork or determination to see it through. Perhaps that is that. Or perhaps there’s more. If I dared to look even further into it, I might find an even deeper problem at the bottom of it all. As it turns out, I have proposed these sorts of projects many times before. I am, apparently, the sort of person who has plenty of big ideas, who talks a big talk—maybe even inspires others to share my dream—but who never tends to see these things through to the very end. And the people closest to me, consciously or unconsciously, know this about me. They may not even know that they know. Perhaps they want to finish the job just as much as I do. But when things get tough, there’s just nothing left in the invisible bank to see them through. They don’t trust me. It might be true that a mustard seed of faith could move mountains. But without even a mustard seed, we can barely move one foot in front of the other.

The hardest leadership lesson in the world is this: trust is fragile. There is only one thing that can keep the flickering flame alight, and it is not sexy. You must stay true, no matter what. As mundane as it may sound, this has become the central goal of my life.

It is a cliche in stories and films to depict kings and generals on the frontlines, leading their people into battle. But in real life nowadays, it’s almost unheard of. Just as modern warfare reassigned generals to rooms with radios and radars, far from the blood and mud of the battlefield, so too modern wisdom has reassigned leaders to places and spaces far removed from the day-to-day labors of their people. “Relentless delegation” is the wave of the future. There are more business books written today about how to “work oneself out of a job” than there are about how to lead others within one. I have no major qualms with delegation, especially if you’ve already cut the path for others to walk. However, the increasing removal of founders, owners and officers from the daily lives and work of their organizations’ members does seem to underestimate the primary source of human motivation.

What moves people, really? Why do people persist in doing hard things? Why venture into the wilderness? Why rush into battle? Despite what a million “mission and vision” statements may proclaim, people follow people, not principles. When we delegate, when we scale, we invite new benefits, of course. But we also open ourselves up to new forms of fragility. It doesn’t mean a leader shouldn’t grow his organization, anymore than a father and mother shouldn’t grow their family. Growth is a blessing. And yet, at every level of growth, the question must still be asked: Not, “What are they working for?” but “Who are they working for? Do they have someone to follow who will not let them down?” For my money, this is what makes or breaks our companies, communities, ministries and families. We are not Christ, but if we hope to be good leaders, we must be like him in this way most of all. We must become trustworthy.

If you enjoyed this post, please hit the LIKE and RESTACK buttons below. Thanks!

Wonderful , Ross! It is always good to lead by example, as you say- to not mind getting muddy and bloody—. Thank you

Key takeaway: if by good leadership Ross Byrd can teach his 8 year old to run a chainsaw, I can too.