The Sacred Square

A Short Story About "Divine Violence"

Friends,

“The Sacred Square” is a short story I wrote a little while back in an attempt to help a friend grapple with a very difficult theme in the Old Testament (and in the New Testament, for that matter). If it rings a bell for some of you, that’s because I posted a rough version of it back then. Recently, though, I decided the story deserved a little more careful attention and editing. So I’m re-releasing it here, complete with a brand new podcast version, for those who prefer to listen. I hope it makes you think.

Preface: Atheism, Modern Morality & the Stoning of the Sabbath Breaker

Sometimes, when reading the Bible, we come across passages which don’t jive well with our modern moral sensibilities. The temptation in such moments is often to proceed to one of two opposite escape hatches, one on the left, shall we say, and the other on the right. The one on the left says something like, “Well, this is embarrassing. See, you can’t really trust these old texts all the time. Parts of the Old Testament reflect a violent tribal people depicting a violent tribal deity. We are more enlightened now than we were then, thank God. Moving on.” Whereas the escape hatch on the right says, “Well, it may seem evil to us, but God can do what he wants. He’s God. And that’s that. Moving on.” But there is a third option, which is to refuse to take either of these escape hatches immediately, that is, to refuse to “move on.” This option entails sitting with the problematic passage—staying in the tension—ruminating on it for days or weeks or years(!). And often enough, deeper layers do come to light.

When Jesus declared to his followers in John 6 that they must “eat his flesh and drink his blood,” many of them got up and left him right then and there. Yet, the Twelve stayed, not because they knew exactly what Jesus meant, but because they had seen enough to know, “Lord, to whom else shall we go?” Of course, it was confusing to remain—especially with Jesus seemingly talking about cannibalism and all—but they somehow knew it would be far more confusing, long-term, if they were to go anywhere else. And they were proved right. In the end, they even came to know much more of what he meant when he said, “My flesh is real food and my blood is real drink,” which, of course, they would have never known at all, unless they had remained.

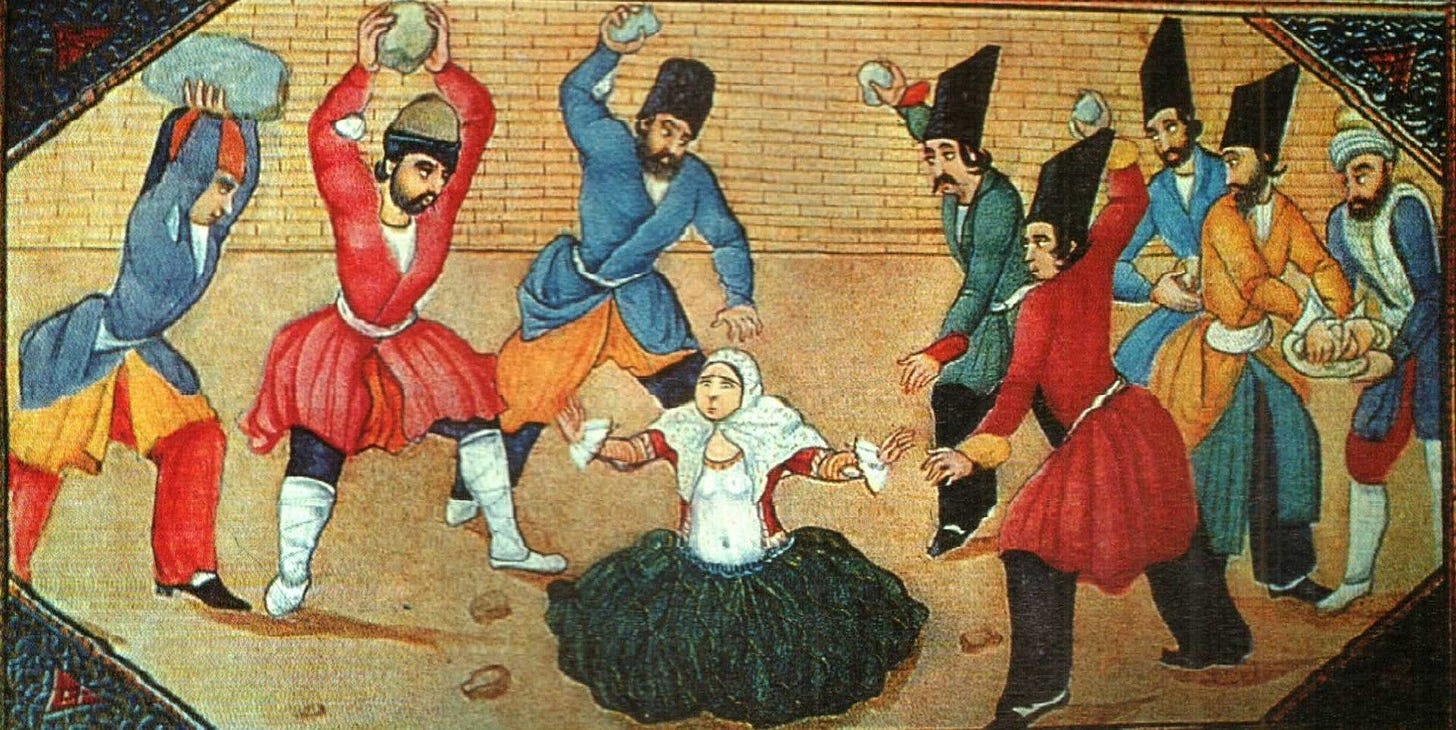

Recently, in our community’s Bible reading plan, we came across one of those difficult passages. In the Book of Numbers, Chapter 15, there is a rather disturbing account of a man being stoned to death for gathering sticks on the Sabbath (vv. 32-36). Here’s the passage:

While the people of Israel were in the wilderness, they found a man gathering sticks on the Sabbath day. And those who found him gathering sticks brought him to Moses and Aaron and to all the congregation. They put him in custody, because it had not been made clear what should be done to him. And the Lord said to Moses, “The man shall be put to death; all the congregation shall stone him with stones outside the camp.” And all the congregation brought him outside the camp and stoned him to death with stones, as the Lord commanded Moses.

After reading this passage, one of my students sent me the following message.

I’m confused by today’s reading…why would God have his people murder a man for breaking the Sabbath? According to my translation, he was just picking up sticks.

And, of course, it’s a very good question. Why stone a man simply for gathering wood on a sacred day? This sort of response seems utterly foreign to our whole modern perspective—even our modern Christian perspective—on morality and human dignity.

As I was thinking about how to respond, I happened to come across a certain viral internet clip. It was a Ted Talk by the author of the best-selling book Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari. And, sure enough, he was musing about where he believes our modern notions of morality and human rights came from. Warning, the clip you’re about to hear is kind of absurd, but here goes…

In summary, Harari is saying that all our values and morals are based on stories, not, as he puts it, on reality. Take a human and cut him open, you find only blood and organs. These stories of good and evil, right and wrong, identity and values, are nowhere to be found.

Now, this is going to sound strange, but, as I was listening to Harari’s argument, and thinking of ALL the ways I’d like to refute it with an argument of my own, my mind somehow kept going back to his word “stories.” Because, of course, he was telling a story too—a story of a people who have evolved over generations to tell each other such powerful myths and legends that they have come to treat them as real, even though, in a kind of dramatic irony, reality has only ever been made out of stuff—flesh and blood, carbon and hydrogen. And then, of course, I thought, “How did all this carbon and hydrogen, flesh and blood come to tell stories in the first place? And why?”

And then I realized that the story of the stoning of the Sabbath-breaker in Numbers 15—that embarrassingly violent passage, which we modern believers might be tempted to gloss over and forget about—does in fact provide its own profound refutation to Harari’s argument. And I was tempted to break it down to you, to show you bit-by-bit, like the parts of a molecule, what I mean. But then I was reminded that the story itself tells more than the explanation ever could. And though Harari seems to want to argue that stories aren’t real, the very structure of his own thinking, speech, and actions proves otherwise.

So I’m not going to explain the Numbers passage directly and show directly how it relates to Harari’s argument. But what I can do is tell you another story, which I think will help make everything a little more clear. And that story is called…

The Sacred Square

“We welcome you here, and you may stay as long as you wish,” the man says. “But you must obey our rules.”

The chief speaks kindly, but formally, it seems to you, though the language is more foreign to your ears than any you have heard. Your guide, himself a member of the tribe, translates with a thick accent. After four full days of travel, the last day and a half on foot through wild terrain without a human in sight, you have arrived at your destination. You and three close friends have made arrangements to live for a time alongside an aboriginal tribe, which has had little to no contact with the world outside.

“Of course,” you reply with a deferential bow. “Please tell us the rules.”

The chief speaks. Your guide interprets. “Do not lie, steal, or murder.”

“Ah, yes,” you say, “We have the same rules where we come from.”

“I have heard this,” says the chief. “But one more thing. It is very important. Never step in the square in the center of the village.” He points to a shape drawn out carefully in the dirt nearby, a square about twenty feet across. Nothing inside it, as far as you can tell. Just…an empty square.

“I see,” you say. “But…why not? I mean, what is it for?”

The chief listens to the translation and squints a little. He shakes his head and repeats himself, “No, you never step in the square.”

“Okay,” you say. Your friends nod and bow. The chief bows back. The four of you are led to your quarters, a relatively large tent, from what you can tell, not far from the central square.

For three months you live peacefully among the tribe. The people of the village are kind and beautiful people. They seem surprisingly hospitable to outsiders like you, and you begin to feel quite at home. Sometimes you’re tempted to think that the people of this primitive village are far more sane, wise, and happy than the people you left back home.

You have now witnessed firsthand that no one ever comes close to stepping in the square in the middle of the village. In fact, they take extra care not to, even sometimes bowing to it as they pass. You and your friends are very bothered by this. It makes no sense. At night you whisper your frustrations to one another. “There’s nothing there. Literally, it’s nothing but dirt.” You have learned enough of the language now to ask others about the significance of the square. But they always answer the same way:

“It is the sacred square.” When you ask why no one is allowed to step inside, they don’t seem to understand the question. If they attempt a response, they only reiterate some version of, “The square is sacred.”

One day, a man is caught stealing a cow from another family. He had apparently planned to take it to a nearby village to sell. The villagers gather around the square—though no one steps inside, of course—and they hold trial. In the end, the man is sentenced to a month’s hard labor to restore the debt owed to the family from whom he stole. This might have seemed a bit harsh to you before you arrived, but somehow it makes sense to you and your friends now.

A month later, shockingly, two men in the village are killed. They seem to have been murdered in cold blood by a disturbed young man who is now missing. After a couple of days, they find the murderer. A solemn trial is held around the square in which the facts of the case are presented and the mourners mourn their loss. The man is deemed guilty of murder. After the trial he is taken out of the village and put to death. Your guide and interpreter, a man you have shared meals with—a warm, caring man, a faithful father and husband—is one of the men who carries him away.

This is vexing to you and your friends. It was one thing for this disturbed young man to do what he did. It is another to see the most peaceful members and leaders of the community resort to this act of violence in response. But it isn’t long before you consider the other complex factors involved. It’s not as though they have a prison they could put him in for the rest of his life (or even for the rest of the year!). And besides, it was quite scary having a murderer loose in the village. So, in the end, you make peace with the tribe’s decision.

Meanwhile, something has been really bothering one of your friends. Though he too had made peace with the execution, he absolutely cannot make peace with the square in the middle of the village. It’s late one night and he begins to complain, a little too loud, you think. “It’s just a square,” he says. “It’s just a damn square. Why are they so obsessed with it? It’s not magic. It’s not anything. It’s the same dirt on that side of the line as it is on this one.”

Your other companions try to shush him.

“You know what?” he says, and stands up. Before anyone can stop him, he is out of the tent, making his way toward the square. Ignoring the hisses from you and his other peers behind him, he steps over the line and turns around. He does a little dance on the inside of the square. Then he tip-toes back to the tent in silence.

Sure enough, nothing happens. You realize then that you had begun to believe that maybe there really was some deep magic about the square, that—what?—some bolt of lightning from the heavens was going to strike him down? How silly you were. Good thing no one saw him. “Never do that again,” you scold. “You’re crazy!” Everyone has a quiet laugh, and then…sleep.

You awake in the early morning to a flurry of activity. Outside the tent, people are rushing back and forth. Small clusters of men and women whisper to one another. Some are arguing. You stop a passerby. “What’s going on?”

“Someone has trespassed the sacred square,” she says, her voice trembling.

How did they know? Maybe there is some sort of magic to the square. You look over at it. Inside the square, clear as day, you see…footprints. Oh, that’s how. Again, you chide yourself inwardly for thinking there was anything supernatural going on. But then…you panic. All they’ll have to do is trace those footprints in the square back to our tent.

You look closely. Thankfully you can’t see footprints anywhere except in the square. Everywhere around the square is too trodden with prints to reveal any one specific set. You let out another sigh of relief. Your friend is still sleeping in the tent. You need to warn him.

But suddenly, a horn blows. A familiar sound. The whole town is being called to meeting around the square, just as with the thief and the murderer. Your friend walks out of the tent. You whisper to him what has happened. After a few minutes, the whole tribe is convened.

“Who among us has trespassed the sacred square?” says the chief. “Make yourself known.”

Silence for a full thirty seconds or more. Then, a low eerie hum begins to rise amidst the people. Deep, eerie throat noises join together all around you, reverberating through closed mouths to crescendo. You close your eyes and grit your teeth, unable to bear the tension of the moment.

Suddenly, it is quiet again. You raise your head to find that your friend—the one who trespassed the square the night before—has stepped forward. “No!” you want to scream. But you don’t.

“It was me,” he says. No one moves. “I did it. I can show you. There’s nothing to it, really.” He is speaking in English, but somehow you know that everyone can understand. “It’s not what you think, he says. “It’s just...Well, I’ll show you…”

He steps in again, turns in a quick circle and steps back out, as though to illustrate some infinitely simple fact of the physical world to a group of very small children, too young to understand.

Several men move toward him at once. The next few moments are a blur. Women and children—even grown men—can be heard wailing, as if with some long-forgotten grief. Some have fallen to their knees. Your friend’s arms are tied behind his back. You do not move to protect him. The crying continues. Fear and sadness and anger merge into one resonant frequency, until finally the chief’s voice can be heard above the cacophony.

The proceedings are short, since, of course, all were witnesses. Your friend is found guilty of trespassing the sacred square. The penalty is death.

Now you are wailing. You grab the arm of your local guide and translator, the man in the village you trust more than anyone.

“Wait!” you plead. “How can this be? We saw what you did with the man who stole the cow. He had to work for a month. You didn’t kill him! And—and my friend just stepped across some arbitrary line in the dirt, and you’re going to put him to death? It can’t be. I thought this place was good. I thought you were better than us. But you are far worse!” Your voice breaks.

The man listens patiently. “You are right,” he says after a moment. “We would never kill someone for stealing a cow. To us, a cow is not sacred.”

“But a square full of dirt is sacred!” you hiss.

He shakes his head. “I have heard there are some in your country who say that a man is nothing but blood and flesh. Do you believe this?”

This enrages you. “Are you saying I shouldn’t care about my friend because he’s only a bit of flesh?”

“I am not,” says the man. “I do not believe that. Do you?”

“No.”

“But some people in your country do. Do they not?”.

“Some say they do.”

“But how then can they say that murder is a great evil? Don’t your people have harsh punishments for murder too?”

“We do. We believe—well, at least, our ancestors who made the laws believed—that human life was sacred.”

“And did your ancestors not know that, if you cut a man open, you find only blood and organs?”

“No, they knew,” you admit. “But they also believed—well, many of them believed—that human beings were made in the image of God.”

The man nods. “So, in your culture, to kill a man is not just a sin against flesh and blood, not even just a sin against that man, but against something higher than all men?”

“I think so,” you say.

“It is the same here.”

“Yes, I know,” you say, “That’s why you put the murderer to death, but this is—“

“You are ignoring your own logic,” the man interrupts. “What is unseen is higher than what is seen…and more real. What is sacred is upstream from what is right and wrong. When you kill a man, you do not only sin against his flesh. You sin against the unseen part of him that makes him most who he is. It is the unseen part that makes murder murder. Without it, the man is only dirt, just like, as you say…”

He points to the square.

“But the square is only dirt,” you say. “Nothing happened when my friend stepped inside. You saw!”

“Ah,” says the man. “You want to say that your friend only stepped from one piece of dirt to another. But I could say the same about the murderer, that he only thrust wood and stone into flesh, nature into nature. And that would be true enough, if that were all you chose to see.”

“Yes, but the murderer ended lives. And life is—”

“Life is what?” Silence.

“You think,” continued the man after a moment, “that I don’t know that the inside of the square contains the same dirt as the outside? I do.”

You shake your head. “So you believe a lie that you know is a lie. And now you’re willing to kill for it!”

“I didn’t say that,” says the man. “I said I know the square is made of dirt. But it is not only made of dirt, any more than you or I or your friend is only made of flesh. The unseen part of the square is also real. If the square were only dirt, then so would you be. And the very idea of murder, even the idea of theft, would be nonsense. But if the square is made of more than dirt, if the square itself is sacred, as I believe it is, then everything else shares in that sacredness in its own way.”

“I just don’t understand why you would do this thing, when all he did was—”

“I am truly sorry about your friend.” The man looks right at you, all compassion in his eyes. He is not much older than you, but at this moment he seems your elder by fifty years or more. “He was ignorant,” he says. “Men should not die for ignorance alone. Though, it happens more often than you might think. Nature itself punishes in this way. Yet we still mourn. You are right to mourn. If your friend could see your tears…if he could know that the weight of your tears and the sacredness of the square are two parts of the same whole—that though one is water and the other dirt, they are both made of the same reality—then he would at least begin to know the consequence of his actions. I pray he will before the end. Then he can die well, which is no small thing.”

“But I…I still don’t understand.”

“You understand more than you admit,” the man replies. “If nothing is sacred, then nothing is sacred.”

If you enjoyed this post, please hit the LIKE button and the RE-STACK button below. It helps more than you might think. And if you’d like to receive future posts to your inbox, please SUBSCRIBE. Thank you.

Really enjoyed this Ross. It's stories that confuse us and push against our commonsense that give us insights into facets of God and following Jesus which we would otherwise miss.

It reminds me a little of how my grandfather speaks about tithing - that if you see it as money paying for a service or toward the upkeep of a building or institution, you're missing the point. If there was a bottomless pit where you could throw your money every week and you never saw it again, but you knew that's what God had commanded you to so, then you should do it. The point is the sacrifice, not the maximised utility of your money.

The more I read, the more I fall in love. You’re one of my fav writers. ✍️

Love this