The Best Thing I Learned In Seminary

Tri-perspectivalism & The Impossibility of a God's-Eye-View

As you may have noticed, humans are not birds. If we want to know an object in our field of vision, we cannot typically fly over it and see the whole thing at once. If the object is small, we pick it up and rotate it in our hands. If it is large, we walk around it in order to see it from different angles. This, for instance, is what you do when you’re shopping for a Christmas tree. Birds would perhaps be very efficient Christmas tree shoppers. Humans have to be more careful. If you have only seen the Christmas tree from one side, you haven’t seen enough to know what you’re dealing with. You have seen a part of the truth about the tree, no doubt. But a judgement based on one true part may amount to a falsity with respect to the whole. You have to walk around the tree—to see it from every side—before you know what you’re looking at, before you can judge whether to buy it and bring it home. In other words, we have to see the same thing from different perspectives in order to know what it truly is. To see a thing from only one side is not merely lazy; it is often dangerous. You are buying into a truth that is not merely under-examined but quite often untrue.

This may seem obvious to you. But you might be surprised just how frequently you and I tend toward a mono-dimensional approach to reality, how often we tend to presume a one-and-done, birds-eye view of certain treasured truths when in fact no such view is available to us. We are not birds. We are, much more so, not God. God’s view is infinite. Ours is finite. And yet, humans have the added disadvantage of forgetting just how finite our view is. We tend functionally to believe that what we see is the whole show. Don’t get me wrong. We can see and know the truth. But from this finite perspective, it is possible to know a truth—to be entirely correct about a certain fact from a certain perspective—and yet still be wrong.

You could imagine someone caught on camera stealing a wallet from someone else. You have seen the footage in high definition, zoomed in on the offending hand and the wallet and the faces of both individuals. “Person A clearly stole the wallet from Person B,” you declare with 100% certainty. “It’s all right there on the screen.” And yet, there may be other facts to which you are not privy, facts which, if you had known them, would have caused you to come to an entirely different conclusion about the event. For instance, imagine a whole room of reliable witnesses all testify to the fact that, before the two men walked in front of the security camera, they watched Person B steal the wallet from Person A. It turns out Person A did not steal the wallet at all. Though, just a moment ago, you might have sworn otherwise, now you see clearly that Person B was the actual thief. The footage, without having changed, has suddenly taken on new meaning. Person A was simply rectifying the situation by taking the wallet back.

This is the power of perspective. And again, it may seem obvious to you, especially if you’ve read Sherlock Holmes or perhaps even watched NCIS. But the power of perspective has a wider application than you might think. It holds especially true in the realm of theology, philosophy, ethics, and biblical interpretation. For instance, just because the Bible says something in a certain verse—and let us assume, as I do, that the Bible is always true—does not mean the application of that verse is at all straightforward. I am not trying to play games here. I believe the Lord meant it when he said, “Thou shalt not kill.” But the one thing we know he did not mean is, “Thou shalt not kill under any circumstance…anything or anyone…ever. Full stop.” How do we know this? Because the same Old Testament which includes this command includes other divine commands to do the opposite. We could begin as early as this line from God’s covenant with Noah in the Book of Genesis:

"Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed, for God made man in his own image.” (Genesis 9:6)

And lest we think this logic is only meant to apply before God’s revelation of the law to Moses, we could give other more direct examples of commands to shed blood which were given to Moses, and then again to Joshua, Saul and others. I realize this is a difficult topic, and I don’t mean to get into it here (sorry). I simply mean to point out that, in fact, “Thou shalt not kill,” does not always, only, in every circumstance mean exactly what it seems straightforwardly to mean. This is not the way biblical ethics works. We do not simply look at a biblical command and know exactly what to do in every case. Don’t get me wrong. I am not saying that the norm, “Thou shalt not kill,” is unclear, much less that it is untrue. It is both true and clear. Yet, the proper application of any norm, even this one, cannot be discerned from the norm alone, but must be discerned in context by means of perspective. You have to walk around the tree before you know what you’re buying.

Enter my favorite seminary professor, John Frame. In his teaching and writing, Frame proposes a system of interpretation that has permanently changed the way I think. He calls it tri-perspectivalism. But in order to understand what that is, it helps first to understand an even more foundational element of Frame’s thought. For Frame, “The meaning of Scripture is its application.” Allow him to explain…

I would even maintain that the meaning of the law is discerned in this process of application. Imagine two scholars discussing the eighth commandment [about bearing false witness]. One claims that it forbids embezzlement. The other thinks he understands the commandment but can’t see any application to embezzlement. Now we know that the first scholar is right. But must we not also say that the first scholar understands the meaning of the commandment better than the second? Knowing the meaning of a sentence is not merely being able to replace it with an equivalent sentence (e.g., replacing the Hebrew sentence with the English sentence “Thou shalt not steal”). An animal could be trained to do that. Knowing the meaning is being able to use the sentence, to understand its implications, its powers, its applications. Imagine someone saying that he understands the meaning of a passage of Scripture but doesn’t know at all how to apply it. Taking that claim literally would mean that he could answer no questions about the text, recommend no translations into other languages, draw no implications from it, or explain none of its terms in his own words. Could we seriously accept such a claim? When one lacks knowledge of how to “apply” a text, his claim to know the “meaning” becomes an empty, meaningless claim. Knowing the meaning, then, is knowing how to apply. The meaning of Scripture is its application. (John Frame, The Doctrine of the Knowledge of God, pp. 66-67)

Frame is speaking, at least in part, about participatory knowledge, a concept to which we have continually returned in the pages of this Substack. “Knowing about,” we have said, is not the same as “knowing.” Reading ten books about soccer does not mean you know soccer. To know soccer, you have to play the game—and keep playing it—possibly for a lifetime. This is what Frame means by “application.” When we become participants in the game, we begin to see and know it from all its different sides, not merely third-person (how the game is played in each and every situation), but also second person (how you must play it, according to its explicit and implicit rules and norms) and first-person (how it feels for me personally to play the game). These are the three perspectives—thus, “tri-perspectivalism”—by which a truth must be encountered before one can be said to know it, according to Frame. He refers to them as normative, situational, and existential.

These three aspects of knowledge are perspectival. You can’t have one without the others, and with each, you will have the others. Every item of true human knowledge is the application of God’s authoritative norm to a fact of creation, by a person in God’s image. Take away one of those, and there is no knowledge at all.

So I distinguish three perspectives of knowledge. In the “normative perspective,” we ask the question, “what do God’s norms direct us to believe?” In the “situational perspective,” we ask, “what are the facts?” In the “existential perspective,” we ask, “what belief is most satisfying to a believing heart?” Given the above view of knowledge, the answers to these three questions coincide. But it is sometimes useful to distinguish these questions so as to give us multiple angles of inquiry. (John Frame, “What Is Tri-Perspectivalism?”)

Hopefully now you can begin to see that the initial Christmas tree analogy was overly simplistic. In my initial image, the potential Christmas tree need only be viewed from different sides, though from the same situational perspective (the facts of the physical tree from every angle). A true judgment of the fitted-ness of the Christmas tree, however, would be much more complex. To choose the right tree, we must view it from the normative perspective (what are the cultural and even divine norms, outside and above ourselves, by which a household Christmas tree can be said to be good and fitting?), the situational perspective (what are the facts of this particular Christmas tree and how do those facts fit with the facts of your car, your home, your family, your budget, etc?), and the existential perspective (what value, function, and meaning does the Christmas tree have to you personally?).

Perhaps this second Christmas tree analogy seems problematic to you for different reasons. “Well, no one actually acts this way," you might say. “They just go pick the prettiest tree they can find, and that’s good enough.” And I don’t disagree. I would add only two small considerations. First, the value of all three perspectives exists whether you are conscious of them or not. You may not consider the normative perspective in purchasing a Christmas tree, but you are still obeying some kind of norm, for good or ill. Second, a Christmas tree purchase may not rise to the highest level of theological import, but some things do. And in such things, we are often equally if not even more susceptible to poor, mono-dimensional judgment.

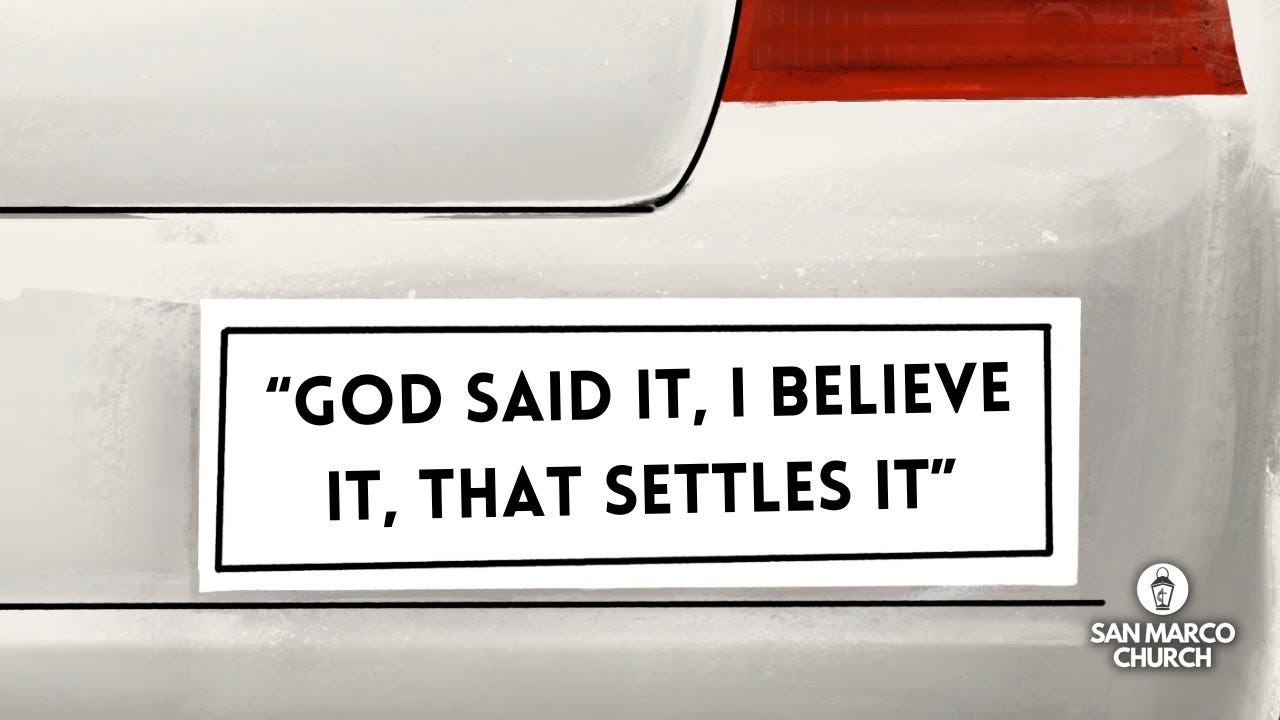

Once again, let us consider the sixth commandment, “Thou shalt not kill.” The most obvious temptation here, for Bible-believing Christians, might be to give the normative perspective its whole due without consideration for the other two perspectives. “The Bible says it. I believe it. That settles it,” is a popular sentiment among especially conservative American Christians. That’s the normative perspective. Ironically, with regard to the 6th commandment specifically, I’m not sure many of them actually believe this, since the same population tends to support the military and the second amendment. Christian pacifism might be a better example of an exhaustively normative view of the sixth commandment. Though Quakers today tend to be more progressive generally, as regards violence they might truly be said to hold the stance, “The Bible says it. I believe it. That settles it.” And, to their credit, the Bible does say it, and not merely in the ten commandments. Jesus himself says, “Turn the other cheek.” The trouble is Jesus and the writers of the New and Old Testament say many other things as well. The norms of Scripture are not given in a vacuum. They have a context (situational perspective) and a motive (existential perspective), which allow them to be truly applied and therefore truly understood. The context and motive of the Lord’s ten commandments must be taken into account when considering how (and if!) a modern Christian is obliged to obey them. For instance, are modern Christians obliged to obey the fourth commandment (to honor the Sabbath and keep it holy)? If so, how and to what extent? Good Christians have disagreed about the proper application of this commandment and continue to disagree to this day.

But it’s not only the biblical norms which come to us with their own context and motive. We too must consider our own situation and motives in interpreting and applying them. Even if we agree that we are the people of “Thou shalt not kill,” “Turn the other cheek,” and “Love thine enemy,” we must still discern how such norms may (or may not) be applied in a given situation for a particular person. Even if we conclude that there is a certain situation in which killing is generally justified (e.g. in war, against an enemy combatant), the justification of said killing may still depend on the existential motives of the person doing the killing. Even in our modern secular law courts, motive plays a key role.

The three perspectives are easiest to apply in the ethical domain, but as you begin to use them, you’ll find they stretch far beyond. All biblical interpretation is perspectival. We are not birds. We are, even more certainly, not God. We have no God’s-eye-view of reality. But God has been gracious enough to give us other means to understand and apply his truths in the world. We may not be able to do so with push-button simplicity, but we can do so. Biblical interpretation, to borrow a notion from Andy Crouch, is more like an instrument than a device. It takes time and patient practice to learn how to play it well. And tri-perspectivalism may prove to be a helpful little tool as you continue to learn how to play. At least, it has been for me.

P.S. Thank you to Jay McCabe for encouraging me to write this piece.

This reminds me of the phrase we use in medicine around imaging: "one view is no view." Basically, you cannot appreciate any given pathology off of one image of it. You have to have multiple, a lot like having to walk around a Christmas tree before being able to appreciate the whole. And that is just for being able to appreciate something with our eyes! Being able to know the things of God whether in the ethics of scripture or circumstances of your life requires so many more views (and a lot of time). Great piece

interesting post! a lot of parallels here with c.s. pierce. i.e. the meaning of a concept is the sum total of its practical consequences for action. also he has a much more highly developed triadic view of reality. frames three perspectives dovetails nicely with the three main divisions of the summa! i wrote at length about my own take on this in my pilgrimmage as first philosophy post.