4 Hot Takes on the Sermon on the Mount

Hi everyone,

In what follows, I try to give a slightly different lens through which to view Jesus’s most famous sermon. Rather than laying the foundation for Christian morality, as is often supposed, I believe the Sermon on the Mount offers a new spin on the ritualistic patterns prescribed in Leviticus and Deuteronomy, which are, for the most part, not about morality. These Old Testament patterns, which appear strange and foreign to us now, generally had less to do with “right” and ‘wrong” and more to do with holiness—how exactly the people of God were to set themselves apart for God through participation in him by faith. Likewise, the Sermon on the Mount is about holiness, which is not exactly the same thing as moral goodness. Once we recognize this (and begin again to do what he said), I believe Jesus’s words can truly become a portal to new life, peace, joy, and freedom, rather than simply a moral burden too heavy for any of us to bear. So without further ado, here are my four hot takes on the Sermon on the Mount…

1. The commands of the Sermon on the Mount are mostly not moral commands.

There is a tendency among many Christians today to use Jesus’s teaching in Matthew 5-7 as a kind of handbook for Christian morality. And, of course, it’s understandable. Jesus is clearly laying out a certain Christian ethic, telling us what to do and what not to do. But I don’t believe the ethic Jesus puts forward is meant to be understood on the moral level. For instance, in recent years, progressive Christians have used the Sermon on the Mount as their foundational source for critiquing the hypocrisy of “the religious establishment,” reminding us that, according to Jesus, true Christians love their enemies, turn the other cheek, give to the needy, and renounce attachment to earthly treasures. This is, of course, true. But not exactly in the sense they mean. That is, inasmuch as their critique is on the moral level, I believe it misses the point of what Jesus is doing in this passage. In fact, on the moral level, conservative Christians could turn around and leverage other passages from the same sermon back at the progressives and accuse them of a similar degree of hypocrisy, using perhaps the passages about adultery and divorce (though, admittedly, Jesus’s teaching on remarriage, morally understood, would be tough on just about everyone these days). The point is, if Jesus meant the Sermon on the Mount to be understood on primarily moral grounds, that is, if he meant to give us a new definition of the types of human actions which should be deemed “wrong” and “right,” then two problems immediately arise: (1) we’d all be in big trouble; and (2) we’d all have to admit that Jesus’s “moral norms” have never become our moral norms, not even for Christians. We do not understand morality that way.

With regard to the first problem, it’s worth acknowledging that there are many (especially Protestant) Christians who would respond, “Exactly! We’re all in big trouble.” That is, they actually understand Jesus to be demanding absolute moral perfection of a sort that he already knows is impossible for any human other than himself to fulfill. And that is the point: he wants us to see how far short we fall. For what it’s worth, this is the interpretation of the Sermon on the Mount I was taught for most of my life. Notice that it’s still a moral interpretation, but different than the ones previously mentioned. Contra the progressive (or conservative) Christians trying to use the Sermon on the Mount as a handbook for social reform, these interpreters believe that Jesus is purposely trying to heighten the demands of the law in order to“increase the trespass” (see Rom. 5:20-21), so that where sin increases—that is, at least, awareness of sin—grace may increase all the more. “You have heard it said, ‘Do not murder’…but I say that if anyone is angry with his brother…” And so on. The cherry on top of this argument is Matthew 5:48: “Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect.” In other words, does Jesus really want us to fulfill all that he has commanded? Does he really want us to be perfect? Yes. But can we fulfill it? Can we be morally perfect? No. Not of our own accord. These commands are given to increase the trespass, to show us what we cannot do, to drive us to him, who alone can make white robes out of our filthy rags.

That is one reading of the text. And as moral readings of the Sermon on the Mount go, it might be compelling, that is, if we understand it to be primarily a moral teaching. As we have seen, it solves problem #1 by embracing it, by saying, “Yes! The moral teaching of the Sermon on the Mount shows us that we cannot fulfill it, and therefore drives us to Christ.” Fair enough. However, it doesn’t deal with problem #2, namely, that no one actually sees morality the way Jesus describes it here. We will leave the Beatitudes out for now (“Blessed are the poor in spirit,” etc), though they could serve as a central part of our argument. But let’s just take some basic examples from the text of seemingly moral commands:

“If someone forces you to go one mile, go with him two miles.”

Of course, at first glance, this sounds like a very good and moral thing to do. But leaving aside what a terrible rule this would be if it were standardized on a societal level, let’s just consider the moral implications of one person doing or not doing this. If someone forces me to go one mile, and, on a certain occasion, I only go with them one mile, would that be immoral? Of course not. Almost no one would argue otherwise.

“If someone wants to sue you and take your tunic, let him have your cloak as well.”

Okay, someone has sued me. Let’s say I give him what he asks—all he has asked—even if I don’t believe he’s in the right. Would it then be immoral if I don’t turn around and give him even more than what he asked?

“Do not resist an evil person. If someone strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also.”

This is a verse that is often brought up to make a moral point. But even for most Christian pacifists I know, “turn the other cheek” is a euphemism for “don’t strike back.” The more extreme ones would perhaps add, “Don’t even defend yourself.” But very few, I believe, would argue the moral principle which “turn the other cheek”—if understood morally—actually implies: that when struck by an evil person, one should go out of their way to give the assailant another opportunity to strike you. And, of course, one would have to go even further still to say that it would be immoral not to do so.

“Give to the one who asks you and do not turn away from the one who wants to borrow from you.”

Again, would it be literally immoral, according to Jesus, to decide not to lend to the one asking on certain occasions? I know no one who would pin this view on Jesus.

But what about, say, someone like St. Francis? He seemed to live by precisely such a rule.

Yes. And that will serve as a fine segue to my second point, because of course, St. Francis did not understand himself to be obeying some common moral code which, if he were a judge or church leader, he might have used to hold everyone else to account. No. He understood Christ’s commands not as mere laws which threatened to bind and condemn him. He understood them as his freedom, as an invitation to live in the kingdom of God here and now. And he was right.

2. The Sermon on the Mount is about how to enter and live in the kingdom of God now.

It’s the cracking open of a heavenly door, showing us not only what it looks like on the other side but how to enter in.

When the rich young ruler asks Jesus how to inherit eternal life, Jesus tells him to obey the commandments (which should already be a hint that even the Ten Commandments are not the straightforward moral principles they might appear to be!). The rich ruler replies that he has done so. So Jesus tells him to sell all he owns, give it to the poor, and come and follow him. Of course, giving all you have to the poor is a good and moral thing to do, but we cannot conclude that this is why Jesus tells him to do so. For starters, he doesn’t give this command to everyone. And furthermore, we can be fairly confident that Jesus is not merely telling this man to “do the right thing” and then he’ll inherit eternal life. No. What he is doing is giving this rich man a way to inherit the treasure of a new and unseen kingdom by faith, that is, by embodying his faith in faithful obedience. Jesus is saying, in effect, “Do you want eternal life? It’s standing right in front of you. Put your faith in me, and you will have it. How do you put your faith in me, you ask? Do what I say.”

The Sermon on the Mount bears out a similar pattern, though in a grander way for a wider audience. And the theme once again is: this is how you enter the kingdom. In other words, this is how you believe in me, how you begin to see the unseen. If you believe not just with your mind but with your obedience…if, like Abraham, you embody your faith in obedient action, you will see God and inherit his kingdom. Jesus’s teaching in Matthew 5-7 proposes nothing less than a new pattern, a new way of embodying our faith in him through actions which center on his love and make his love a reality in our everyday lives. And this happens not merely by knowing the fact of his love, but by participating in his love through our own investment and agency.

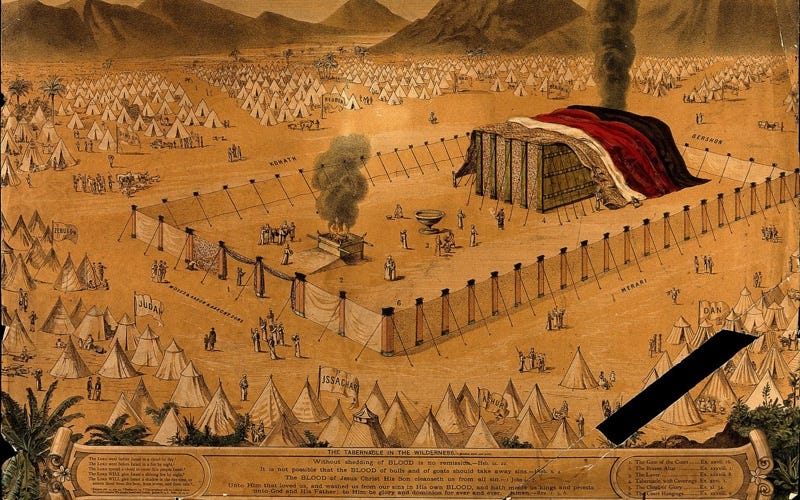

Of course, this type of teaching is not unprecedented. A ton of the Old Testament is about this same thing. Leviticus, for instance, is absolutely chock full of divine commands, “Do this and don’t do that.” And yet it would be absurd to understand most of those commands as primarily moral teachings. “Offer your sheep on the north side of the altar, not the south.” “Anoint the priests in exactly this way.” “Do not wear clothing which mixes wool and linen.” “Do not plow with an ox and a donkey together.” “Do not trim the hair on the side of your heads.” Etc. The immediate effect of such commands was not to make the Israelites “good people,” but, as Yahweh explicitly reminded them, to set them apart from all other peoples and false religious patterns. Admittedly, there are moral commands dispersed throughout these same sections of Scripture (e.g. against incest). But even such commands must be understood to have more than mere moral import. The most obvious common thread between the moral and ritual commands in Leviticus is that they all serve to make the people holy, which is not a mere synonym for “very good,” but rather means “set apart” or more specifically, “set apart for God.”

What I am saying is that the seemingly random requirements of the ritual code and the sacrificial system in the Old Testament are far from arbitrary. On the contrary, they are the musical notes of a holy dance that must be danced to be understood and appreciated. They are the intricate means by which the people of God were able, in some small way, to begin to participate in the marriage of heaven and earth by embodying it with the everyday patterns of their very lives. They were being “set apart” in order to be brought together with God. Every prescribed pattern in the text meant something before they could even understand what it meant. They had to do it to know it.

As one small example, let’s take the command against mixing two types of material in clothing. The idea is not that the mixture of wool and linen was somehow objectively morally wrong. Rather, keeping wool (which represented “below”) and linen (which represented “above”) set apart in your everyday clothing was a pattern that physically reinforced the fact that if a true reconciliation of above and below (read: heaven and earth) were possible, it could not happen casually and unceremoniously. The fact that proves this point is that the priest in the holy of holies did in fact wear both wool and linen in his prescribed garments. Why? Because that was the proper place and way for heaven and earth to meet. As in a marriage, one does not awaken the consummation of love before its time, not because it is a bad thing to consummate a marriage, but precisely because it is a holy thing, which must be set apart until the proper moment when the two can become truly and unfailingly one. Of course, for the people of Leviticus, this fact was not often explained conceptually as I have just attempted to do. Rather, it was lived, even worn around on their very clothing.

Likewise, Jesus’s entire ministry is about the reconciliation of heaven and earth. Obviously, he is the one who finally accomplishes this union, but even he does not often speak of it in conceptual terms. Rather, in keeping with the pattern of the Scriptures he inherited, in the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus gives us a way to live the truth, not just to download it as an idea. Not unlike Moses in the Book of Leviticus, Jesus paints a picture of holy patterns. But he is the new Moses. His patterns are not primarily about clean and unclean, inside and outside, above and below, but about love and trust, which set us apart for the kingdom of heaven, which is now at hand. And these patterns—far from being morally meritorious—become the means by which we receive more and more the gift of grace, the fruit of the Spirit, and the blessings of the Father. When we turn the other cheek, go the extra mile, pray in the closet, and give to those who ask without letting our left hand see what our right hand is doing, however imperfectly and in baby steps, we begin to participate in Christ’s body—in his death and in his resurrection—right now. Such acts are not merely the fruit of faith but are indeed the instantiation of our faith in Him. They are what faith looks like in the world.

My point in all this is not that morality is unimportant to God. Surely doing what is right and refraining from what is wrong matters immensely to God. After all, he is the maker of morality. My point is that morality is common. In fact its central power lies in how very common it is. Far from being unique to Christians, most moral principles that Christians hold have been shared by many diverse cultures across the world and throughout time. (C.S. Lewis has gone to great lengths to make this point.) But what we find in Leviticus, with all the specifics of temple sacrifices and priestly requirements, is a kind of parting of the clouds of common morality, affording at least a glimpse of the holiness beyond, of the place where heaven meets earth, which not all cultures have been party to. Holiness, by definition, is not common. Likewise, the Sermon on the Mount is a kind of new Leviticus, revealing the holy patterns by which the people of God may live in the presence of God now. Yet, again, not through “clean and unclean,” etc, but through trust and love.

3. We would never have even heard of the Sermon on the Mount unless the man who spoke it actually dared to do it.

The Sermon on the Mount is perhaps the most famous religious teaching of all time. But the reason we all know it is not merely because of what Jesus said. Many or most of the things he said in it had already been stated in one way or another in the pages of the Old Testament. Many of them could have also been stated by Buddha or any number of other great religious teachers. The reason we remember these particular words—and the reason they have come to have such power over even our secular society’s way of understanding reality—is that Jesus’s words here sum up more than a principle. They sum up a Person. Jesus himself uniquely embodied what he taught. The word became flesh not just in the womb of Mary but in the complex world of human thought and deed, of sin and temptation, of the seeming invisibility of the Father, and the inevitability of suffering and death. When the stakes were highest, when holiness, righteousness, and love seemed most impossible, Jesus married word and deed, heaven and earth, God and humanity…in Himself.

On this point, almost all Christians of course agree, yet it’s still a hot take to those outside. Those shopping through mystical teachers and moral philosophers for that perfect set of principles by which to inaugurate their own version of utopia will perhaps not find what they’re looking for in the words of Jesus’s most famous sermon. But what they will find is the one occasion on earth where word and deed found perfect unity. And perhaps, where word and deed found perfect opportunity for unity in us. Which leads me to my last and hottest take…

4. We can do it too.

Oddly enough, among my Evangelical peers, this may be the claim that gets the most pushback. What do I mean, “we can do it?” Sure, by God’s grace and the power of the Holy Spirit, we could, in theory, slowly develop a lifestyle of joyful generosity, deep humility, and almost constant prayer. Perhaps we know others who seem to have done so, however imperfectly. Perhaps we can even imagine radical saints of the past who treated their own property—even their own lives—as though they were God’s and not their own. But for normal, everyday Christians, even the simplest commands of the Sermon on the Mount often seem out of reach. Even if they aren’t meant as a moral burden, even if they’ve been given to us as a spiritual invitation into relationship with him, it seems nonetheless obvious that we cannot perfectly fulfill such a standard. At first glance, Jesus’s words certainly seem better suited to expose how far we fall short than to give us some new means of communion with him now. “Be perfect as your heavenly Father is perfect,” pretty much sums up the problem. If we’re going to be perfect, we think, it certainly won’t be on this earth and it probably won’t have anything to do with our own efforts to obey. It will be according to his healing hand, which remakes us, some day, into his likeness.

To this, I would say, yes and no. Yes, our perfection must be His doing, but no, this is not just some dream for after we die. And furthermore, it’s not without our effort, though of course we cannot earn a hair’s breadth of it on our own. What do I mean?

Well, first off, perfection in the Bible does not mean what you think it means. I have done a whole podcast about this elsewhere, but basically, we moderns have come to redefine the word “perfect” to mean “flawless.” This is not what it means in the Bible. In our world of modern technology, it’s hard for us to see outside the paradigm of mechanisms. A perfect machine, we say, can produce the same thing the same way every time. And then we apply this notion of perfection to ourselves…and make ourselves miserable, since we can’t compete with our perfect machines. But we weren’t meant to. And no one would want that kind of perfection anyway. In the Bible, the word “perfect” does not generally mean flawless. It means complete, mature, finished. So, the perfect tree wouldn’t be the tree that is flawlessly symmetrical in every way with no knots or bruises. The perfect tree would be the tree that has grown to its full capacity, bearing all the fruit it was meant to bear. Likewise, God has not called us to be flawless. He has called us to be finished…to become everything we were meant to be in him.

Of course, we still cannot become anything without the healing hand of God remaking us. That’s like Christianity 101. “There is no one who does good, not even one” (Rom. 3:12). Forget being perfect. We could not even breathe without his grace upholding and animating our very existence.

But the question is how does he remake us? How does he make us perfect? I have gone to great lengths in past posts to show that God has not chosen to do very many things by divine zap. If he did, surely he would have “saved us” once for all immediately after the fall. But no. The story of the Bible is of a patient kingdom built on the divine long-game of covenant invitations, failures, exile, forgiveness, and restoration, all of which continue in a seemingly indefinite cycle, until finally culminating in the greatest failure of all, the cross, which becomes the greatest victory of God. No one could save us this way but him. In the formula of our salvation, there is no splitting of responsibility, as though God gives 50% and we give 50%. No. God’s part is 100%. And yet, paradoxically, I don’t believe that that makes our part 0%. The whole point of God’s long game is that the formula for our salvation is a relationship. We are saved and made into everything we were meant to be through a relationship with him. And like any relationship, this requires our investment, our agency as well as his. It cannot be zapped into existence. It’s not that sort of thing. Our new life is because of him, and though we have done nothing to earn it, yet it requires all of us. The weird math of the new covenant is 100% God, 100% us. He will settle for no less than all of you marrying all of him.

In this light, the Sermon on the Mount can be understood as a wedding proposal. Jesus is saying, in effect, give up the treasures your own kingdom can provide. Give them up. Moth and rust and death will destroy them anyway, so what do you have to lose? Cast aside your former loves and come and live in my kingdom. Share in my riches. Inherit all that my Father possesses. All that is mine shall be yours. Only come. I know the way seems confusing. The so-called treasures of your kingdom can be easily seen. The treasures of my Father’s house are harder to see, at first. But if you begin to empty yourself of those old patterns and rewards and follow me, I promise you will see. And you will be, finally, happy.

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God.

This is profoundly helpful to me. Our church staff is taking the year to go through the Sermon on the Mount via memorization and teaching. I’ve been tasked with putting together the teaching elements over the course of 2025. Your work is influencing my thoughts and even the structure of my teaching to better understand the implications of this for our lives as believers. Thank you for your work!

This feels wholesome….like a dislocated joint has been put back in its place.